The Venezuela-Iran connection and what Maduro’s capture means for Tehran, explained

As critics of Washington’s capture and criminal indictment of Venezuelan head of state Nicolás Maduro made connections to other US regime-change operations in the Middle East, US Secretary of State Marco Rubio told CBS’s Face the Nation: “The whole foreign policy apparatus thinks everything is Libya, everything is Iraq, everything is Afghanistan. This is not the Middle East. And our mission here is very different. This is the Western Hemisphere.”

He also emphasized that Venezuela can “no longer cozy up to Hezbollah and Iran in our own hemisphere.”

There are clear implications of the Maduro arrest with respect to US-Iran policy and President Donald Trump’s calculus on strategic action against Washington’s adversaries. The US president has indicated he is weighing “very strong” options on Iran as demonstrations there escalated and the death toll rose sharply over the weekend, according to rights groups.

And as Rubio indicated, the operation could also have a more immediate impact on Tehran’s interests and operations abroad—with Venezuela serving as a foothold for Iran and its proxies in the Western Hemisphere.

Our experts break down Iran’s ties to Venezuela and the impact Maduro’s capture could have on Tehran’s interests both in and outside of Iran’s own borders.

Iran-Venezuela relations: From oil to resistance axis

Venezuela-Iran relations have strengthened in recent years: Both countries are oil producers, both have struggled under a robust Western sanctions regime, and as Tehran upgraded its relationship with Caracas, its proxies, such as Hezbollah, have established themselves inside Venezuela’s borders—creating a strategic foothold in the Western Hemisphere.

Both countries are founding members of the Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC) and had an official relationship before the 1979 revolution in Iran that saw the overthrow of the shah. As the Iranian revolution unfolded and the Islamic Republic came to power in Tehran, Venezuela was one of the first countries to recognize the new Iranian government.

This relationship intensified, however, when Maduro’s predecessor, the late Venezuelan leader Hugo Chavez, became president in 1999.

Between 2001 and Chavez’s death from cancer in 2013, Chavez and his Iranian counterparts engaged in dozens of diplomatic visits, and “the two countries signed an estimated three hundred agreements of varying importance and value, ranging from working on low-income housing developments to cement plants and car factories,” according to analysis from the Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS).

Under Chavez, Tehran’s development projects in Venezuela “boosted Chavez’s image and advanced his anti-imperialist agenda throughout the region.” And through Venezuela, Tehran leveraged the partnership to bolster its posture in South America, including in Bolivia and Nicaragua.

By the tail-end of Chavez’s rule in 2012, Iran’s investments and loans in Venezuela were valued at $15 billion, according to CSIS.

Beyond oil and diplomatic agreements, gold smuggling has also shaped the relationship model between Tehran and Caracas. Venezuela holds the largest gold reserves in Latin America (just counting Central Bank reserves, and without including geological gold resources, which would place the country in the fifth place for gold reserves worldwide). Additionally, reports indicate that gold has been smuggled to Iran for years as a mode of payment for Iranian assistance to revive Venezuela’s oil sector.

A base for Hezbollah and the IRGC

Joze Pelayo, associate director for strategic initiatives and policy at the Atlantic Council’s Scowcroft Middle East Security Initiative, explains

Against this backdrop, Iranian-backed Hezbollah and its affiliates have used Venezuela as a strategic hub in the Western Hemisphere. The country has served as a sanctuary for Hezbollah to evade sanctions, a center for operations and money laundering, and a base for its transnational criminal and drug trafficking network.

Hezbollah has flourished in key locations in Venezuela—establishing itself within business networks such as Margarita Island and the Paraguaná Peninsula, both with coastal access and a significant Lebanese diaspora community.

Iran also used the gold market in Venezuela to finance Hezbollah’s operations.

In 2022, a seizure order signed by former Israeli Defense Minister Gallant and published by the National Bureau for Counter Terror Financing in the Ministry of Defense exposed a smuggling ring involving gold being transported on sanctioned Iranian flights with proceeds directed to Hezbollah.

In addition to all these exchanges, Iran’s Quds Force (the external arm of Iran’s Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps responsible for asymmetric warfare, cover operations, and intelligence) maintains a robust presence in Venezuela to support Maduro in times of crisis, according to a report from December 2025.

The hierarchical structure in Venezuela is headed by Ahmad Asadzadeh Goljahi, who oversees operations and heads the “Department 11000,” a Quds Force subunit linked to international terrorist plots, and “Department 840,” involved in overseas assassinations. It is then no surprise that the Iranians attempting to abduct US journalist Masih Alinejad from her home in New York were supposed to make a stop in Venezuela before taking her to Iran.

Maduro’s capture and the potential realignment of Venezuela with the United States represent a major setback for the Quds Force operations and financing. Such a shift could significantly disrupt the group’s transnational criminal and drug-trafficking networks, oil-smuggling scheme, and other illicit activities tied to Hezbollah and the Islamic Republic of Iran.

One potential silver lining: Under US custody and influence, Maduro (and possibly Acting President Delcy Rodriguez) could provide critical intelligence as witnesses and cooperators, assisting to expose the extent of these networks, how to properly root out these toxic elements from the country, and key figures the United States could go after next.

A US signal to Tehran

Kirsten Fontenrose, nonresident senior fellow at the Scowcroft Middle East Security Initiative, explains

The Maduro case is strategically relevant less as a template than as a signal. It suggests a US willingness to act decisively against leaders already criminalized and sanctioned, rather than allowing standoffs to persist on the assumption that the risk of escalation alone will deter action.

The Trump administration framed Maduro’s capture as a law-enforcement arrest rather than a military campaign. The United States did not invoke humanitarian intervention, collective self-defense, or congressional authorization for interstate hostilities. Instead, it relied on longstanding criminal indictments and sanctions authorities. Maduro has been under US indictment since March 26, 2020, for narcotics trafficking and narco-terrorism, and he has been subject to comprehensive Treasury sanctions well before the January 2026 operation. The legal basis for such extraterritorial law-enforcement action rests on domestic authorities rather than the law of armed conflict—a distinction that is controversial but not unprecedented in US practice.

For Tehran, the relevance is not the legal argument itself but the political signal embedded in its use. Iranian strategic planning has long assumed that US concern about escalation—particularly actions that could be interpreted as leadership targeting—would impose practical limits on Washington’s behavior. The Maduro episode complicates that assumption. It also reinforces a second point: US leverage does not depend exclusively on military operations. In this case, years of sanctions enforcement, financial pressure, indictments, and diplomatic isolation preceded the arrest, demonstrating that decisive outcomes can be pursued through non-military instruments even in high-risk contexts.

That sequencing intersects with current thinking about the timing of pressure on Iran. Analysis by Rapidan Energy Group Chief Executive Officer Scott Modell published in late 2025 argues that early 2026 presents unusually favorable market conditions for intensified pressure on Iranian oil exports. The analysis points to soft global demand growth, rising non-OPEC supply, spare capacity among OPEC+ producers, and subdued price expectations, suggesting that concerns about oil-price spikes—often a key political constraint on US action—would be less binding in the first quarter of 2026. If that assessment holds, market considerations would be unlikely to restrain US policymakers contemplating additional economic pressure on Iran during this period.

Trump’s public statements following the Venezuela operation reinforce this interpretation. He framed the action in terms of accountability and deterrence, not regime change or nation-building. His emphasis on speed and decisiveness is consistent with earlier US decisions favoring limited, time-bound uses of force—particularly in counterterrorism and retaliatory contexts—over extended military campaigns.

This posture aligns with the policy orientation of figures shaping the administration’s approach. Homeland Security Advisor Stephen Miller has emphasized coercive clarity; Special Envoy to the Middle East Steve Witkoff has advocated transactional diplomacy backed by leverage; Vice President JD Vance has expressed skepticism toward open-ended military commitments. Reporting also suggests a US Central Intelligence Agency leadership preference for intelligence-driven, more aggressive collection and disruption posture.

Recent US actions elsewhere provide additional context. Strikes against Iran-aligned militias in Iraq following attacks on US personnel in 2024, and counter-ISIS airstrikes conducted with host-nation consent in Nigeria in December 2025, illustrate a preference for responding quickly to defined threats without prolonged warning or phased escalation. These cases do not establish a doctrine, but they reinforce the impression of a US approach that favors early, bounded action over incremental response. In this context, Operation Absolute Resolve is meaningful because it unsettles a core assumption within Tehran—that leadership insulation and escalation risk reliably constrain US action.

The core implication for Iran, then, is strategic rather than operational. The Maduro seizure suggests that the United States is prepared to act decisively against leaders who are already criminally indicted, comprehensively sanctioned, and politically isolated, and that it may do so during periods of internal strain rather than waiting for those pressures to resolve.

None of this implies imminent leadership targeting in Iran. But it does suggest that Washington is reassessing assumptions about timing, leverage, and leadership vulnerability.

Further reading

Sat, Jan 3, 2026

Experts react: The US just captured Maduro. What’s next for Venezuela and the region?

Dispatches By

What does the future hold for Venezuela following the US raid that removed Nicolás Maduro from power? Atlantic Council experts share their insights.

Thu, Jan 8, 2026

As Iran protests continue, policymakers should apply these key lessons

MENASource By

The Iranian people are bravely leading the current protests. It is essential to keep the focus on them.

Mon, Jan 5, 2026

The Trump Corollary is officially in effect

Dispatches By

The Trump administration has a unique opportunity to reimagine the contours of US hemispheric defense for years to come.

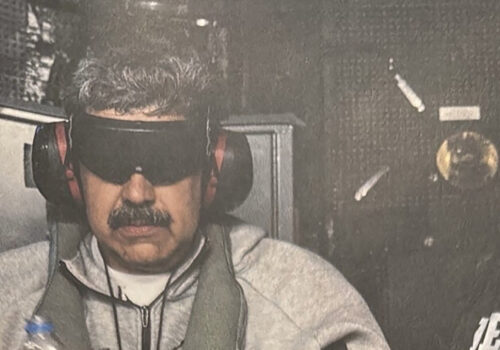

Image: Sheikh Ali Haidar, Shiite leader and representative in Venezuela, poses for a photo with people in front of a mural depicting late Hezbollah leader Sayyed Hassan Nasrallah, in Caracas, Venezuela October 17, 2024. REUTERS/Leonardo Fernandez Viloria TPX IMAGES OF THE DAY