Peru has erupted once again. The assassination attempt against a cumbia band in Lima on October 8 triggered a tumultuous month for the country. On October 10, President Dina Boluarte was removed from office, and Congressman José Jerí was inaugurated as Peru’s eighth president in ten years. In the days that followed, Peruvians took to the streets in what have become the country’s largest protests in the past five years. Clashes with police have left at least one dead and dozens injured.

The demonstrators are not only protesting the new president, who has been accused of corruption and sexual assault. The protests are the political manifestation of something deeper: the steady advance of organized crime into everyday life and the collapse of public confidence in the Peruvian state’s ability to protect its citizens. As Peru approaches its April 2026 elections, the moment holds both promise for democratic renewal and risk of democratic collapse.

As Peruvians prepare to head to the polls, the insecurity crisis will be top of mind. Over the past three years, Peru has experienced an unprecedented rise in organized criminal activity. Between 2019 and 2024, reported extortions increased sixfold, and this year every third Peruvian reported knowing a victim of extortion, many of whom are small business owners. Homicides, too, have doubled since 2019. And in January of this year alone, there were 203 percent more homicides than in January 2017. What was once seen as a problem of border towns or drug corridors has become the daily reality of small and medium-sized businesses—the country’s true economic engine.

Peru’s crisis is no longer just about corruption or governance. It is about the basic survival of the rule of law.

In cities such as Trujillo and Chiclayo, bus operators and construction firms now pay weekly “quotas” to criminal groups. In Lima’s districts, even market vendors receive extortion calls demanding transfers through digital wallets. Many of these workers belong to Peru’s vast informal sector, which employs nearly seven out of ten Peruvians and forms the social base that has now turned against the political establishment and is demanding solutions. When extortion payments and successive killings became commonplace, strikes and street protests followed against a government perceived as absent or complicit.

This explosion of criminality is the predictable outcome of a decade in which Peru’s institutions have been eaten away by self-interested politicians, resulting in political instability. Beginning in 2016, a Congress dominated by the fujimorismo movement began to abuse its oversight powers, engaging in what legal scholars term “constitutional hardball”—exploiting procedural rules to turn impeachment into a tool for political leverage rather than accountability, as seen during the impeachments of Boluarte and former President Martín Vizcarra.

The country was also undergoing the aftermath of Operation Car Wash, a far-reaching set of investigations originating in Brazil, during which Peruvian prosecutors launched aggressive corruption probes against Peru’s pre-2016 political class. The probes ended with four former Peruvian presidents convicted of corruption. Former President Alan García, who was accused of bribery, committed suicide as police entered his house to apprehend him. Former ministers, presidential contenders, business leaders, and mayors across Peru were swept up in corruption probes, effectively purging the political elite that had once promised to renew the country after the fall of Alberto Fujimori’s regime in 2000.

Unfortunately for the country, what emerged after the Operation Car Wash probes was not a cleaner class of leaders but a more fragmented, parochial, and self-interested one—far easier for organized crime to penetrate. Peru’s Congress, now one of the least trusted institutions in the hemisphere, has often acted as a shield for illicit interests. In recent years, lawmakers have quietly advanced legislation that has reduced penalties for certain crimes, weakened controls on political financing, and obstructed efforts to vet local authorities for corruption. Behind these moves lies a new generation of politicians, many of whom are under criminal investigation for corruption and other offenses. With institutions hollowed out, prosecutors underfunded, and police leadership constantly reshuffled, criminal economies have flourished.

Peru is now less than six months away from national elections, and the outlook is uncertain. After a decade of political chaos, citizens are exhausted and cynical, and the party system is in ruins. The danger is clear: When democracy cannot guarantee security or stability, it loses its moral and practical legitimacy.

The moment could go either way. On one hand, the democratic reflex remains: Peruvians still take to the streets, still reject corruption, and still demand that a competent state guarantee basic services. If leveraged the right way, these demands could be channeled by a democratic and reformist leader willing to rebuild Peru’s institutional arrangements and salvage its democracy.

On the other hand, the ground for populism has never been more fertile. Candidates who promise “order at any cost” will likely find a receptive audience among voters who feel abandoned by their government and terrorized by crime. Promising results in the fight against crime, an opportunistic leader may yet destroy what’s left of Peruvian democracy.

Peru’s crisis is no longer just about corruption or governance. It is about the basic survival of the rule of law. The October protests should not be seen as another episode in the country’s cyclical instability but as a warning that the old model—political chaos insulated from economic collapse—has possibly reached its breaking point. Unless the next government restores both security and institutional credibility, Peru’s democracy risks becoming not merely ungovernable, but unrecognizable.

Martin Cassinelli, who was born in Peru, is an assistant director at the Atlantic Council’s Adrienne Arsht Latin America Center.

Further reading

Fri, Oct 10, 2025

Four questions (and expert answers) about Peru’s presidential impeachment and what’s next

New Atlanticist By

Peruvian President Dina Boluarte has been removed from office following a vote in Congress, with legislator José Jerí replacing her as president.

Thu, Mar 27, 2025

Peru’s crime wave: A populist opening or a chance for reform?

New Atlanticist By Martin Cassinelli

Solving Peru’s security crisis will require institutional reforms that combat political corruption and address the root causes of crime.

Tue, Jul 2, 2024

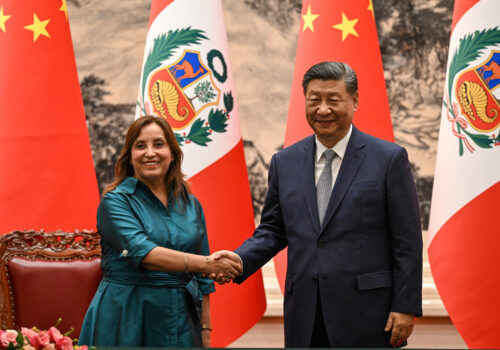

What the Peruvian president’s state visit to China means for US economic diplomacy

New Atlanticist By Martin Cassinelli

Peruvian President Dina Boluarte recently traveled to Beijing to meet with Chinese leader Xi Jinping. Washington should take note of the growing Peru-China relationship.

Image: Protesters participate in a march organized by the youth collective "Generation Z" to express their discontent with the election of Peru's new President Jose Jeri, following the impeachment of former President Dina Boluarte by the Congress of the Republic, in Lima, Peru, October 12, 2025. REUTERS/Sebastian Castaneda.