Democracy at a crossroads: Rule of law and the case for US engagement in the Balkans

Bottom lines up front

- The Western Balkans sit at a critical junction between NATO, the European Union (EU), and the eastern spheres of influence of Russia and China. Unchecked instability and democratic decline in the region would directly threaten European security and US interests.

- US democracy assistance in countries such as Serbia, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Albania, and others must specifically address three pillars: fostering people-centered strategies, strengthening the rule of law, and safeguarding political processes.

- While the EU has invested heavily in the Western Balkans, it cannot foster democratic development in the region alone. The United States should complement European efforts by engaging political parties, energizing civil society, and rewarding meaningful democratic reforms.

This issue brief is part of the Freedom and Prosperity Center’s “The future of democracy assistance” series, which analyzes the many complex challenges to democracy around the world and highlights actionable policies that promote democratic governance.

Introduction: A region undergoing transformation

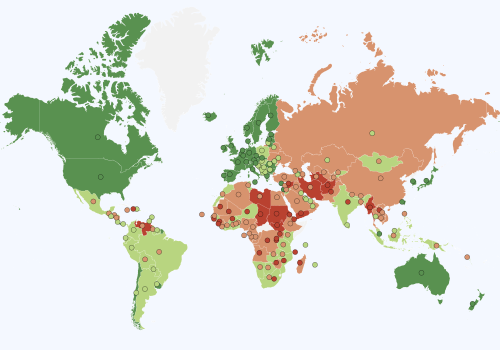

Since the third wave of democratization—the global surge of democratic transitions beginning in the mid-1970s—Europe has often been regarded as a leader in the field of liberal democracy. In its 2024 Democracy Index, the Economist Intelligence Unit ranks Western Europe as the highest-scoring region worldwide, with an average of 8.38—making it the only region to record a net improvement in democratic performance during the latest annual cycle. However, this snapshot only captures part of Europe’s democratic story and can be misleading, given the complex challenges confronting many of its subregions.

Over the past fifteen years, Europe has endured a “polycrisis”—including the eurozone crisis, the migration crisis, climate change, the COVID-19 pandemic, and the Russia-Ukraine war—all of which have strained democratic institutions and weakened public cohesion.

Europe faces two primary authoritarian adversaries: Russia, which employs election interference, military aggression, and other forms of destabilization, and China, which wields influence through commercial trade deals, loans, and strategic alliances. Together, these pressures accelerate democratic backsliding across the continent.

In the Western Balkans, these dynamics are magnified by elite corruption, foreign interference, and internal political conflict—factors that block long-term democratic progress and stall European Union (EU) integration. The nations in this region face a constant balancing act between the West and its authoritarian rivals in Moscow and Beijing, striving to grow their economies while potentially jeopardizing security and stability. Without increased US support, the Western Balkans could become a serious vulnerability for the EU, with implications for the security and sovereignty of both NATO and the broader West.

The need for a revitalized, regionalized US democracy assistance approach

Electoral manipulation, the erosion of the rule of law, and authoritarian instability undermine US-European trade, weaken security alliances, and open the door to Russian and Chinese influence. Moscow and Beijing—through disinformation, political infiltration, and economic leverage—have made the Western Balkans a particular focus. Both employ tailored strategies to exploit the weaknesses of the nations in the region—particularly with respect to their election processes, security mechanisms, and political divisions.

Given these circumstances, US democracy assistance in the Western Balkans is vital. Situated between the EU, NATO, and the eastern spheres of influence of Russia and China, the region occupies a critical geopolitical junction. Economically, the Balkans function as a transport hub for maritime trade, energy pipelines, and migrant flows, making it a flash point for European stability.

Today, the region faces intense pressure from the competing economic and political influence of China, Russia, Iran, and other rivals. Left unchecked, the Balkans could serve as a staging ground for authoritarian powers to entrench their hold on Europe. Current developments in the region underscore that this threat is no longer hypothetical:

- Serbia’s deepening ties to Moscow and Beijing—evident in its energy dependence, military cooperation, and expanding digital-surveillance infrastructure—pose direct threats to transatlantic interests.

- Russia’s sway over Republika Srpska obstructs Bosnia and Herzegovina’s path toward NATO and EU integration, while promoting constitutional instability that undermines national unity.

- Montenegro and North Macedonia, though NATO members, are increasingly vulnerable to hybrid threats from Russia and China, owing to weak institutions and growing political fragmentation.

To be effective, US democracy assistance must reflect the varying dynamics across the Balkans, from balancing Western ties with Russian and Chinese incentives to navigating complex internal conflicts amidst deteriorating democratic institutions. These challenges require programs that improve governance accountability and address frozen inter-state conflicts by working with legitimate political parties and local actors. Revitalized, region-specific democracy assistance is necessary to protect US interests and reinforce European democratic security. Supporting democratic development abroad strengthens US security, prosperity, and global influence, while delaying this support further endangers the United States and its allies through long-term instability and conflict.

In the Western Balkans, democracy is facing internal and external pressure

Today, the six countries comprising the Western Balkans are classified as hybrid regimes, reflecting the region’s persistent democratic decline and institutional fragility. Future democracy assistance must counter the persistent influence of Russia and China, which exploit energy and economic dependence to shift the Balkans away from EU integration.

Serbia

Serbia has wavered between pro-Western gestures and deepening ties with Russia and China—exemplified by its decision to provide military support to Ukraine while refusing to impose sanctions on Russia. According to the V-Dem annual reports, Serbia has experienced rapid democratic decay since the early 2000s under the Serbian Progressive Party (SNS). Over the past decades, the ruling party has entrenched its control over the judiciary and the media, undermining democratic checks and electoral competition.

The December 2023 snap elections revealed widespread manipulation, including group voting, falsified voter registration, and targeted attacks on election observers. The government’s growing alignment with Moscow and Beijing, including recent acquisitions of surveillance technology and energy deals with China, threatens Serbia’s European trajectory and regional stability. These developments not only signal the absence of free and fair elections but also invite authoritarian influence on NATO’s southeastern flank.

Since 2024, students have organized mass mobilizations to protest widespread corruption. These demonstrations are likely to continue, emphasizing the need for US support in fostering pluralism and protecting political contestation.

The unresolved conflict between Kosovo and Serbia continues to fuel internal unrest, violence, and protests. Serbia’s refusal to recognize Kosovo’s 2008 declaration of independence has deepened resentment between populations, restricted access to public services in northern Kosovo, and undermined democratic norms. While the United States and most EU member states support Kosovo’s sovereignty, Serbia is backed by authoritarian powers, including Russia, China, and Iran. This continued denial, along with Serbia’s support for parallel structures in Serb-majority areas, remains a major barrier to Kosovo’s integration into the EU, the UN, and other international institutions.

Kosovo

In Kosovo, internal ethnic tensions and stalled dialogue with Serbia continue to destabilize governance. The May 2024 clashes, which included violence against NATO forces, highlight the fragility of peace in the region. Currently, Kosovo and Serbia share responsibility for public services in northern Kosovo: Serbia supplies education and health care, while Kosovo oversees law enforcement and the court system. This arrangement, however, has left the Serbian minority vulnerable. Prime Minister Albin Kurti deployed heavily armed police across the region, evicted Serbian institutions, banned the use of Serbian currency, and took other provocative actions, prompting roughly 10 percent of Kosovo’s Serbs to leave the country over the past year.

Politically, while Kurti’s Self-Determination Movement won the largest share of votes in the 2025 parliamentary elections, his inability to secure a majority or form a coalition with major opposition parties has stalled democratic reforms. The prime minister’s hardline stance toward the Serb minority, which appears aimed at consolidating domestic support, has drawn criticism from both Western partners and opposition groups. In response, the United States and the EU suspended financial assistance to pressure Kurti to re-engage with inclusive governance and align with international norms. The resulting political dissonance continues to complicate coalition-building and delay key democratic initiatives aimed at reducing internal ethnic tensions, underscoring the need for external assistance.

Bosnia and Herzegovina

Governance remains stagnant in Bosnia and Herzegovina due to an outdated power-sharing arrangement and ethnically fragmented leadership resistant to meaningful reform. The stalled EU accession process and the exclusion of civil society from decision-making have undermined democratic momentum and weakened citizen trust. With political elites increasingly insulated from accountability, institutional resilience is eroding, and democratic contestation faces the risk of further collapse without stronger international support and grassroots mobilization.

Bosnia and Herzegovina’s democratic decline has been sharper than in other Balkan states. In Republika Srpska—a political entity that emerged from the violent breakup of Yugoslavia—Bosnian Serb President Milorad Dodik has worked to suppress public contestation, recriminalize defamation, and align the territory with the Kremlin’s anti-Western agenda. Dodik’s admiration for Vladimir Putin has facilitated growing Russian influence, undermining independent media and silencing opposition voices. In return, Dodik has received Russian political backing and propaganda support.

While Dodik’s mandate was revoked in late August following an appeals court verdict sentencing him to a one-year prison term, his influence has already entrenched ties to Russia and fueled intense contestation of central institutions. These authoritarian shifts are part of a broader ethno-nationalist strategy that heightens vulnerability to state capture and weakens institutional pluralism.

To reinforce the court’s decision, the Central Election Commission of Bosnia and Herzegovina has called early presidential elections in Republika Srpska. Scheduled for November 23, 2025, the OSCE Mission to Bosnia and Herzegovina and other international entities have voiced support, emphasizing the need for free, constitutional, and democratic elections and a peaceful transfer of power.

North Macedonia

Democratic governance in North Macedonia continues to be undermined by low public trust in judicial institutions, media polarization, and widespread corruption. Citizens perceive the judiciary as politicized and ineffective, even as landmark trials against former officials have concluded. Efforts to digitize courts and increase transparency remain promising but insufficient without broader structural reform. Corruption remains deeply entrenched in procurement processes and political appointments, while anti-corruption agencies are underfunded and lack prosecutorial power. Meanwhile, ethnic and political divisions continue to block electoral reform and erode public confidence in representative democracy. While civil society remains relatively active, government hostility toward critical NGOs signals a shrinking space for civic participation.

North Macedonia’s democratic trajectory has been weakened by increasing political polarization, institutional paralysis, and unresolved identity conflicts with EU members. Since 2022, the opposition party VMRO-DPMNE and the far-left party Levica have obstructed parliamentary proceedings to push for early elections, delaying key judicial appointments and agency confirmations. These deadlocks have stalled the Constitutional Court’s functionality, leaving only four of the required nine judges seated and risking a constitutional crisis. Similarly, state agencies such as the Judicial Council, the public broadcaster board, and antidiscrimination commissions remain vacant due to legislative obstruction, undermining government capacity and the rule of law.

These divisions intensified following the 2022 EU-facilitated “French proposal,” which aimed to resolve Bulgaria’s veto over North Macedonia’s accession negotiations. While the deal unblocked the EU path, it required controversial constitutional amendments recognizing the Bulgarian minority. The ruling Social Democratic Union of Macedonia (SDSM) coalition accepted the compromise, triggering mass protests, fueling nationalist backlash, and galvanizing Eurosceptic sentiment. The opposition launched multiple failed referendums and accused the government of “high treason,” stalling consensus on reforms necessary for EU integration. While the government’s acceptance of the proposal allowed accession talks to begin, it also deepened identity politics and weakened democratic cohesion.

Montenegro

Montenegro’s 2020 elections marked a critical turning point, ending the Democratic Party of Socialists’ (DPS) rule and opening the door to democratic renewal. The new coalition government, led in part by United Reform Action’s (URA) Dritan Abazović, entered with a reformist mandate centered on EU integration and anti-corruption. However, ideological fragmentation and a limited majority produced political instability and stalled reform efforts. Today, judicial appointments remain politicized, anti-corruption efforts are faltering, and deep-rooted patronage networks resist institutional change. The coalition’s collapse in 2022 and the formation of a minority government with DPS support highlighted the fragility of Montenegro’s democratic transition.

Amid Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, the EU expedited Montenegro’s accession process as a geopolitical priority. While the country remains a top candidate for EU membership by 2028, this acceleration has come at the expense of EU democratic standards. Despite progress, media politicization, weak judicial independence, and institutional capture persist. The EU’s lenient conditionality—prioritizing regional stability over reform—risks reinforcing superficial compliance. US democracy assistance should focus on strengthening the rule of law, protecting independent media, and supporting civil society to ensure Montenegro’s accession reflects genuine democratic consolidation rather than merely geopolitical expediency.

Albania

Albania’s democratic system is historically fragile and deeply conflicted. Prime Minister Edi Rama and the Socialist Party (SP) hold a strong majority, having secured a fourth consecutive term in the 2025 parliamentary elections with 52.2 percent of the vote. Although the country’s elections are competitive and professionally administered, they take place in a polarized environment marked by allegations of vote-buying and the use of public funds in underprivileged areas to influence outcomes. The SP’s practices undermine pluralism and weaken local governments, which often struggle to provide basic services.

The main opposition, fragmented between factions of the Democratic Party, has failed to meaningfully challenge the government, resulting in diminished parliamentary oversight. This dysfunction culminated in violence in late 2023, after which the government passed restrictive laws curbing opposition activities.

Civil society contributes to national debates, but its impact is often limited due to underfunding, exclusion from policymaking, and occasional co-optation by partisan interests. The media landscape remains largely independent and frequently holds public officials accountable; however, ownership is concentrated in the hands of politically connected elites who leverage their platforms to influence parties and government actors. These insufficient accountability mechanisms have fueled disinformation and deepened public distrust—a vulnerability that Russia could exploit.

Despite these challenges, Albania has a strong foundation of civil society and independent media. The country needs comprehensive support that strengthens civic participation, protects independent journalists, and establishes equitable funding mechanisms for municipal governments.

Reaffirming ties with the EU

The EU recently met with Western Balkan leaders to conceptualize a Growth Plan for the Western Balkans. The meeting included pre-financing payments under the Reform and Growth Facility for North Macedonia, Albania, Montenegro, and Serbia, and further incentivized Kosovo and Bosnia and Herzegovina to pursue reforms.

Emerging deals included new flagship investments in clean energy, initiatives to integrate the region into the EU Single Market, and measures to enhance digital connectivity. Each of these steps outlines technical areas of alignment between the EU and the Balkans, yet questions remain about the future of democracy in the region.

The Western Balkans remain caught between competing pressures: democratic deterioration, unresolved regional conflicts, and growing authoritarian influence. While the EU has invested heavily in the region’s integration, technical improvements alone cannot guarantee democratic development. Therefore, the United States must support the EU’s expansion efforts while emphasizing the importance of democracy. This requires a revitalized approach—one that engages political parties, energizes civil society, and rewards meaningful democratic reforms.

A revitalized approach to democracy assistance

US democracy assistance should embrace three pillars: people, the rule of law, and political processes. These pillars can be broken down into thematic priorities—anti-corruption measures, the protection of independent media and civil society, the empowerment of political parties and contestation, and other vital actions to revitalize democratic progress.

Fostering people-centered strategies

Democracy can only be sustained with inclusive policies that foster an informed, engaged, and educated public. In the face of authoritarian power—which has provoked mass protests and ethnic tensions, creating openings for Chinese and Russian influence—incorporating people-centered objectives is vital to mitigate internal conflict. The United States should therefore prioritize civic education, inter-ethnic dialogue channels, and youth engagement, especially in areas where political violence and protests are prevalent.

Application examples

In Kosovo, this strategy would involve programs fostering interethnic dialogue between Albanian and Serb youth in schools and community spaces. Assistance could also expand civic education initiatives in Serb-majority areas and empower youth-led organizations focused on reconciliation, rights awareness, and political participation. In addition, the United States should provide legal and technical assistance to civil society groups seeking to hold municipal leaders accountable, particularly in border regions.

The United States should counter concentrated executive power through media literacy training in Republika Srpska, stronger protections for journalists and civic actors, and forums to address misinformation and anti-Western rhetoric. Ensuring access to education and multiethnic safe spaces would help mitigate the long-term effects of President Dodik’s autocratic, pro-Kremlin legacy, and support intra-group dialogue in preparation for a democratic election.

Serbia’s student-led protests reflect a desire to challenge government corruption and demand public safety. The United States should support this mobilization by investing in youth-led civic initiatives, combining education with inclusive services for ethnic minorities. However, progress between Serbs and Albanians will remain challenging unless Serbia’s political leadership accepts internationally recognized borders.

Public services and rights must be non-discriminatory and inclusive of all minority populations. The United States should also work with judicial institutions in the Western Balkans to ensure protection for citizens facing disparities.

Supporting the rule of law

Building an independent, non-discriminatory judicial system is vital for reducing conflict during peace negotiations and to prevent executive overreach. US democracy assistance can deploy resources and anti-corruption support in Montenegro to encourage neighboring nations to uphold democratic standards, thereby addressing entrenched ethnic divides and intra-state violence.

Application examples

In Albania, this strategy would prioritize strengthening anti-corruption organizations to curb executive abuse and the unfair treatment of opposition parties and municipal institutions. Cooperating with the Special Structure against Corruption and Organized Crime (SPAK)—which has successfully prosecuted high-level officials—should be expanded to include legal training, protective measures, and transatlantic cooperation opportunities. SPAK’s credibility offers a potential framework for broader rule-of-law assistance in North Macedonia, where transparency in public procurement and prosecutorial independence remain insufficient. Judicial reform in both countries must be accompanied by public awareness campaigns to build trust in institutions and deter political interference.

These themes should be applied to Montenegro, where politicized judicial appointments and weak enforcement mechanisms continue to undermine democratic transformation. As a likely future EU member, Montenegro must strengthen its political institutions, which in turn must be held accountable by independent courts and judges. Similarly, prioritizing Montenegro’s democratic and economic alignment would provide a model for other Balkan states pursuing EU integration.

Finally, in cases of severe ethnic tensions or disparities, the United States must ensure that judicial development promotes inclusive and non-discriminatory services for citizens. This will be vital in Kosovo and Serbia, where stalled dialogue efforts weaken public services and heighten conflict, as well as in other multiethnic states such as North Macedonia, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Serbia, and Montenegro. Supporting judicial institutions will not only build public trust but also protect opposition parties from executive overreach and political repression.

Safeguarding political processes

Political parties have had inconsistent levels of impact in the Western Balkans. Fair competition and coalition-building are vital to strengthen democracy and counter state capture. US assistance should directly engage with political parties to improve inclusivity, policy development, and voter mobilization.

Application examples

Montenegro’s recent election of the United Reform Action (URA) demonstrates the promise of a democratically driven government. In line with this pillar, the United States should address political fragmentation by supporting cross-party dialogue mechanisms, while also creating space for civil society members to participate in policymaking.

Similar mechanisms can be applied to Kosovo, Albania, and North Macedonia, where opposition parties struggle with ideological fragmentation. Open debates, local council meetings, and forums featuring civil society organizations and political representatives would help align citizens’ priorities and party platforms. Technical training should also be extended to countries with ethnic divisions, such as Kosovo and Serbia, focusing on inclusive policymaking and youth engagement.

Finally, in states facing autocratic takeover, such as Bosnia and Herzegovina, this strategy would promote platforms that transcend ethno-nationalist lines and foster cooperation in coalition building. With many Western Balkan states reliant on opposition parties to revitalize democracy, US assistance must prioritize fair and inclusive political competition. By integrating political parties into assistance efforts rather than sidelining them, the United States can help restore the democratic dialogue necessary for government reform. People-centered mobilization, institutional reform, and the renewal of political processes must go hand in hand to ensure democratic resilience across the Western Balkans.

Strategic implications for the United States

A three-pillar strategy—centered on people, the rule of law, and political processes—provides a pragmatic and adaptive framework for revitalizing US democracy assistance in the Western Balkans. As the region struggles with authoritarian interference, ethnic conflict, political fragmentation, and democratic decay, sustained US engagement is critical to prevent long-term instability. Democracy assistance not only builds institutional resilience and civic participation but also protects strategic US interests by stabilizing NATO’s southeastern flank, advancing EU integration, and countering Russian and Chinese influence. To ensure long-term stability and democratic momentum in one of Europe’s most volatile regions, the United States must treat democracy assistance as a core component of its foreign policy and global leadership.

about the authors

Stephen Nix is the senior director for Europe and Eurasia at the International Republican Institute.

Megan Tamisiea is a researcher with an MA in Democracy and Governance from Georgetown University.

Related content

explore the program

The Freedom and Prosperity Center aims to increase the prosperity of the poor and marginalized in developing countries and to explore the nature of the relationship between freedom and prosperity in both developing and developed nations.

Image: 28.06.2025 Belgrade Serbia Politics/Life Vidovdanski protest/ anti-government rally-daily anti-corruption demonstrations. Flag of Serbian south province Kosovo no surrender. IMAGO/Aleksandar Djorovic via Reuters Connect.