Europe needs a new energy option that isn’t Russia. It should turn to North Africa.

Russia’s invasion of Ukraine and the subsequent sanctions regimes have made one fact very clear: the world, particularly Europe, is heavily dependent on Russian crude oil and natural gas exports and will be for at least the next three to six decades, according to my analysis.

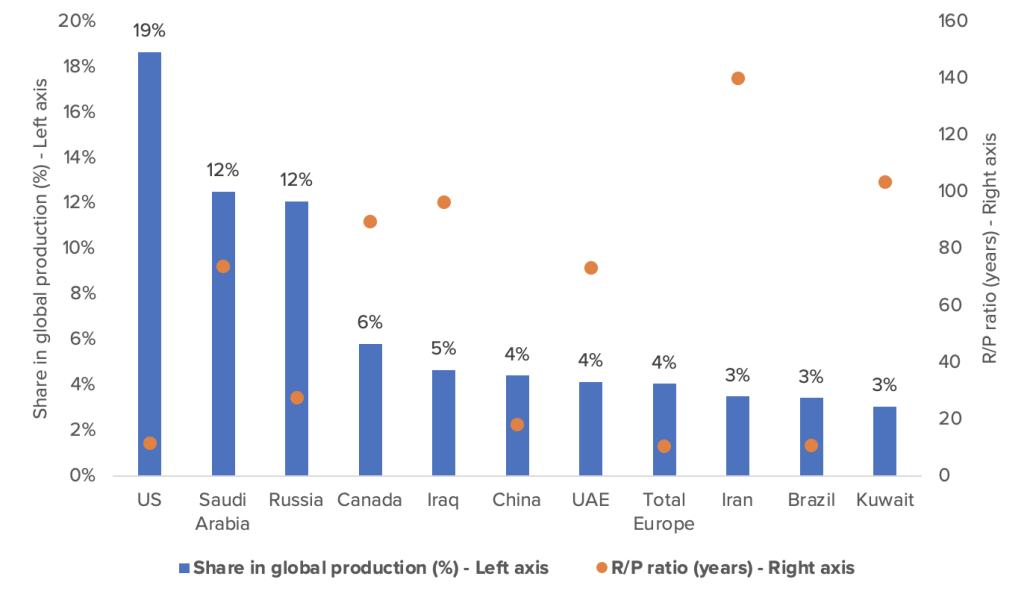

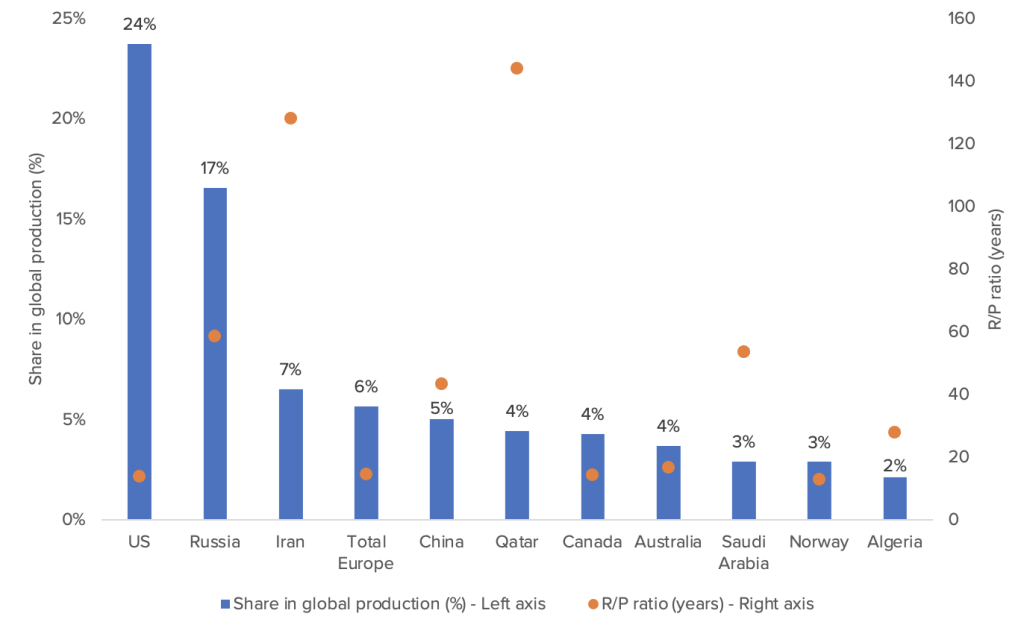

Russia accounts for 12.1 percent of crude oil production with a reserve-to-production (R/P) ratio of 27.6 years, while Europe is responsible for just 4 percent of global oil output and has a much smaller R/P ratio of 10.4 years (Figure 1). Additionally, Russia accounts for 17 percent of natural gas production with an R/P ratio of 58.6 years, while all of Europe is responsible for only 6 percent of global gas output, with an R/P ratio of just 14.5 years (Figure 2). Therefore, it is no surprise that 47 percent and 25 percent of Europe’s natural gas and oil imports, respectively, are sourced from Russia.

Figure 1. Share in global crude oil production and R/P ratio, 2020

Figure 2. Share in global natural gas production and R/P ratio, 2020

Europe’s energy security landscape will become direr in a decade. Its proven oil and gas reserves will be depleted in just 10.4 and 14.5 years, respectively, making the continent even more dependent on energy imports (Figures 1 and 2). The United States cannot provide much assistance in this regard as its R/P ratios for oil and natural gas are very similar to that of Europe (Figures 1 and 2). Canada could provide an oil lifeline for Europe. However, according to my calculations, this would require Canada to triple its production in the next decade—a highly unlikely task—leading to the depletion of its reserves in less than 30 years. Even then, Canada can only meet a portion of Europe’s oil demand and not its natural gas demand (Figures 1 and 2).

The combination of production rates and R/P ratios points to the fact that, for the foreseeable future, Europe will remain highly dependent on Russia for its crude oil and, most importantly, natural gas imports. However, Russia has proven to be an irresponsible and unreliable actor. The Persian Gulf region is also not completely reliable and the competition over its fossil energy resources, especially natural gas, is only going to increase as easily-accessible reserves deplete elsewhere in the world—such as in the United States, Canada, and China—and global demand continues to grow. This leaves Europe with one reliable strategy for its energy security in the long run: renewables.

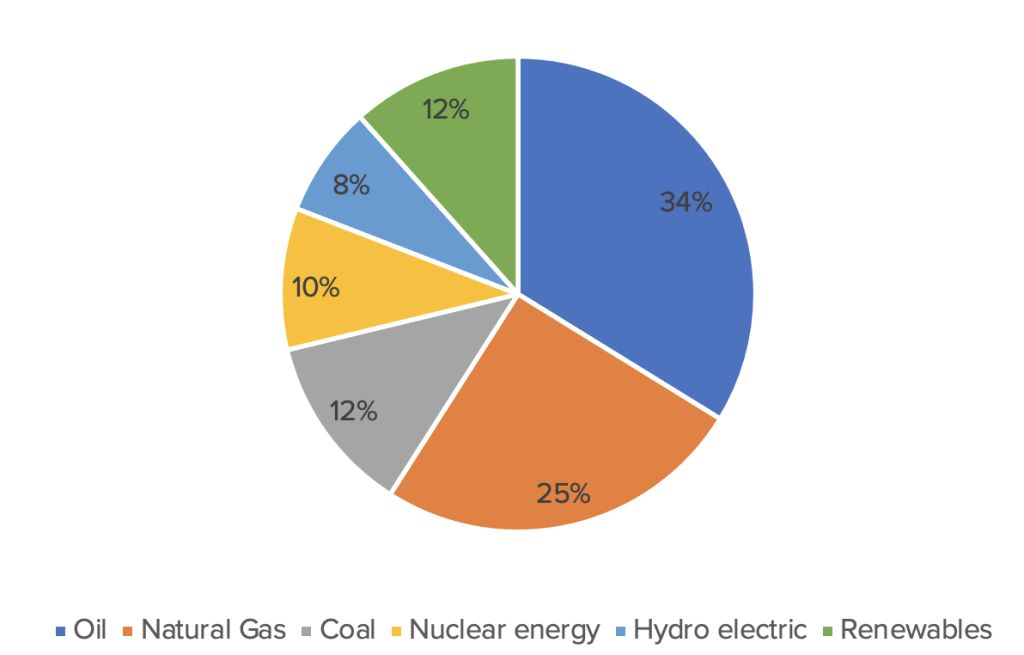

As of 2020, renewables—hydropower and other renewables—constituted roughly 20 percent of Europe’s total energy consumption (Figure 3), an increase from 10 percent in 2005. This figure is slightly higher for European Union countries. By 2030, the EU plans to have 40 percent of its total energy consumption sourced from renewables and reduce the share of oil and coal in its energy mix. Although this is an ambitious target, fossil fuels would still account for half of the EU’s energy consumption a decade from now. When Europe and US reserves are about to be depleted, it leaves the EU highly vulnerable to Russia’s weaponization of oil and natural gas and the Persian Gulf’s relatively unstable political and security dynamics. Hence, Europe must get more aggressive and ambitious on increasing the share of renewables in the continent’s energy mix, which is also in sync with its 2050 net-zero greenhouse emission target. North Africa’s massive solar energy potential is a crucial component of this strategy.

Figure 3. Europe’s energy mix, 2020

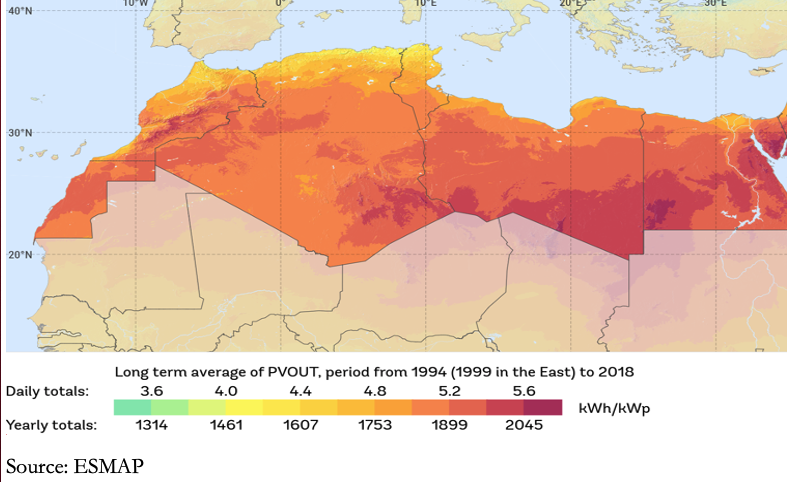

Today, North Africa accounts for 13 percent of Europe’s natural gas and 10 percent of its oil imports. In other words, Europe is the destination for more than 80 percent and 60 percent of the region’s total natural gas and oil exports. This is significant in Europe’s energy landscape. However, North Africa has the potential to play an even more substantial role in Europe’s energy mix, especially because of its massive solar resources. More than 90 percent of North Africa has direct normal irradiation larger than 5 kWh/m2(Figure 4), which is ideal for the operation of concentrated solar powerplants (CSP).

Figure 4. Direct Normal Irradiation in MENA (kWh/m2)

CSPs employ specialized mirrors to concentrate the sun’s rays, creating adequate heat to generate the steam needed to turn the turbines that generate electricity. In the power tower systems, the energy from sunlight will heat molten salt, which can retain the heat—even for up to several days—to produce electricity later. Hence, CSP power tower systems have the potential to generate electricity at night and other times with low sunlight energy, making them highly comparable to powerplants that run on fossil fuels. The massive heat content produced in CSPs can also be used to generate green hydrogen, which is a model energy source in heavy transport and energy-intensive industries, such as steel and cement.

In 2020, Germany presented its National Hydrogen Strategy, planning to invest €9 billion to increase hydrogen production. €2 billion of this amount is allocated to increase production outside of Germany. Given its massive solar and wind resources, the Sahara Desert in North Africa is ideal for production of clean hydrogen. Moreover, the current oil and gas pipeline network between the two regions can be reconfigured to transport the hydrogen generated in North Africa to Europe. Morocco, a forerunner in renewable energy industry in North Africa, has already signed an agreement with Germany to set up a pilot clean hydrogen plant in Morocco, with the goal of reducing 100,000 tons of CO2 emissions.

If less than 0.25 percent of the Sahara Desert was equipped with CSPs, it would be more than sufficient to meet the electricity demand of all of Europe. Moreover, with the growing electrification of the transport industry and increasing use of hydrogen in heavy transport, energy-intensive industries, and practically all manufacturing, North Africa’s massive solar potential would play an even more important role in Europe’s net-zero transition and energy security in the long run.

Theoretically, a mere 1.5 percent of Sahara Desert’s area equipped with CSPs would be sufficient to meet all of Europe’s energy needs. This is because, in addition to the electricity produced in solar power plants, the green hydrogen produced using solar energy has the potential of replacing fossil fuels in the future. Besides boosting Europe’s long-run energy security and meeting its increasing clean energy needs, solar power and hydrogen production in North Africa would contribute to economic development and social stability in North Africa and create much-needed jobs in the region, making such cooperation a win-win for both parties.

However, many challenges remain. For one, financing for such large-scale projects is hard to secure, especially given the history of political instability in much of North Africa. Secondly, China has entered the competition for developing the region’s solar-energy industry. Finally, the colonial history of Europe in North Africa complicates matters. In the end, the current Russia-Ukraine crisis has made it clear that Europe has no other option but to reduce its dependence on Russian oil and gas imports, and rapidly so. For this to happen, Europe must take a closer and renewed look at its Southern neighbors.

Amin Mohseni-Cheraghlou is a macroeconomist at Atlantic Council’s GeoEconomics Center and an assistant professor of economics at the American University in Washington, DC.

Further reading

Tue, Jun 29, 2021

If Raisi wants to improve the Iranian economy, price controls are where to start

IranSource By Amin Mohseni-Cheraghlou

Lawmakers and government officials in Iran repeatedly revert to the same set of failed populistic economic policies, failing to make short-term sacrifices that benefit the country in the long term. One such policy is price controls, a favorite in the toolkit of Iranian policymakers, who have attempted to control persistently high inflation rates over the past decades, but obviously with no success.

Tue, Jul 6, 2021

Ensuring our energy security in a sustainable way in the MENA region and beyond

MENASource By Ariel Ezrahi

In our globalized world, providing energy needs and combating climate change will require cooperation across borders. If the Biden administration is to be successful in promoting affordable and cleaner sustainable energy at home and abroad, it will be critical to engage with partners across the globe, particularly in the Middle East, where much of the world’s oil is produced.

Tue, Sep 1, 2020

Energy cooperation in the Middle East is a necessary step toward regional security

MENASource By Ariel Ezrahi

Mutual energy dependencies can help mitigate political tensions, creating incentives to cooperate and possibly facilitating a positive momentum towards solving some of the MENA region’s thornier outstanding political conflicts

Image: Mohamed Ossama, Project Director for solar energy at Taqa Arabia walks after an interview with Reuters near photovoltaic panels at the Benban plant in Aswan, Egypt, November 17, 2019. Picture taken November 17, 2019. REUTERS/Amr Abdallah Dalsh