In recent years, Central Asia has become increasingly important to a vast array of countries, which have been enticed by the region’s rapidly developing markets, proximity to China and Russia, vast energy and mineral resources, and growing role as a transport hub through projects such as the Middle Corridor. Central Asian states are deepening ties with countries from Saudi Arabia to India while developing political autonomy and distinct identities.

In the United States, however, Central Asia occupies a strange position: strategically important enough to demand attention, yet distant enough that few are willing to commit the substantial economic and political resources required to build US presence in the region. The United States occupies a similarly awkward place for many Central Asians. Though many welcome pragmatic relations with the distant superpower, these are often burdened by geography, domestic US and Central Asian political complications, and the presence of nearby Russia and China. Furthermore, few Central Asians relish the idea of being relegated to the chessboard of a “great game” between superpowers and seek to establish an empowered and autonomous identity on the global stage.

To navigate the dilemma between Central Asia’s vast importance and the challenges that efforts to build US presence in the region would face, the United States should look to its allies better established in the region, especially Turkey, South Korea, and Japan. By building a mechanism to coordinate and communicate on policy, such a “Central Asia Quartet” could act as a force multiplier to each country’s individual efforts, allowing the United States to make a substantial impact at minimal economic and political cost.

No hegemony needed

Officially, US strategic priorities in Central Asia have not been updated since 2019. This strategy emphasizes six areas: strengthening sovereignty and independence, combating terrorism, supporting the now-defunct US-backed government in Afghanistan, promoting connectivity with Afghanistan, protecting human rights, and securing openings for US investment.

In practice, however, US policy on Central Asia has moved away from Afghanistan and human rights and increasingly focused on the development of energy and critical minerals bound for the West and strengthening the Middle Corridor. When it comes to these policy objectives, the United States can promote its goals without fighting an uphill battle to establish widespread economic, political, military, and cultural presence. In fact, unless the American people are willing to commit enormous resources to a little-known region thousands of miles away from home, an indirect approach to engaging with the region could lay a more secure foundation for US-Central Asian relations in the long run.

Among the challenges that the United States faces in promoting its interests in the region are a distinct lack of political and economic capital in Washington, high risks and operating costs for US companies, and poor cultural understanding. The United States must also contend with local apprehension toward working with Americans that is driven by the prominence of nearby China and Russia, as well as a desire among Central Asians to avoid becoming pawns in a great-power competition. The United States would be far better positioned by working in concert with its allies that are already present in the region.

Introducing the Quartet

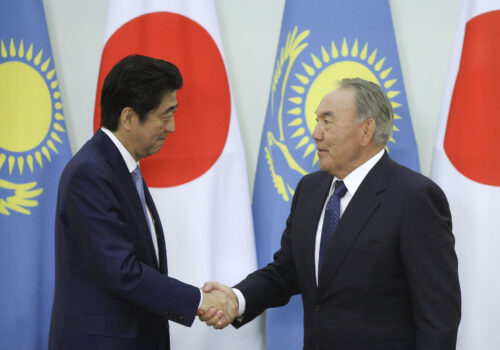

Of the United States’ allies, Turkey, Japan, and South Korea stand out as the best established in Central Asia, each with deep corporate, political, and cultural ties to the region. The nature of these ties varies by country: Japan is a leading provider of official development assistance, facilitates vast technical aid programs, and is a major financier of infrastructure and energy projects. With over five hundred thousand ethnic Koreans across the former Soviet Union, South Korea has deep cultural connections to Central Asia alongside a formidable corporate presence, especially in energy, critical minerals, and heavy industry. Bolstered by common linguistic and cultural ties, Turkey has directed considerable energy into shoring up its political and economic ties with the region, including as a founding member of the Organization of Turkic States. Today, some four thousand Turkish businesses operate in Central Asia in sectors including hospitality, infrastructure, and increasingly defense. Both South Korea and Turkey consistently rank among the most important trade partners for Uzbekistan and Kazakhstan, while Turkey ranked fourth in terms of trade volume for Kyrgyzstan.

Though each country has largely set policy independently, the foundations for cooperation have already been laid. US businesses, including Caterpillar and Bechtel, have used partners from third countries to operate in Central Asia for decades. Turkish and Japanese companies have also cooperated extensively on projects in Uzbekistan and Turkmenistan. Each of these four countries has designated energy, critical minerals, and transport connectivity as key features of their regional policy priorities, and these sectors also indirectly promote Central Asia’s economic and political autonomy.

Beyond de-risking, knowledge sharing, and distributed financing, there are further distinct incentives for each country to participate in the Quartet. Like the United States, Central Asia remains on the political periphery for Japan and South Korea, though they both have greater ties to the region than Washington. Further coordination with allied countries could offer a low-cost method for expanding these ties. Though Turkey has established the strongest presence of the four countries, Ankara could use help from its partners to expand it engagement as well. Turkey’s presence in the region is restrained by the country’s affinity for pan-Turkic ideology—appealing to some Central Asians but complicating to others—as well as economic instability and technical limits in some highly specialized fields.

Importantly, all four countries in the Quartet have strong bilateral relations with one another. Turks and Koreans often refer to each other as “brothers” owing to Turkey’s participation in the Korean War, strong bilateral cultural exchange, and increasing defense ties. Japan and Turkey similarly have a warm history, sometimes described as “two nations, one heart.” In August, Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan even suggested Japan and Turkey lead the reconstruction of Ukraine and Syria. And Japan and South Korea have witnessed significant progress in their relations over the past decade.

The imperative for cooperation and coordination in Central Asia between the Quartet countries is nothing new, as recent Atlantic Council publications on the benefits for the United States of cooperating with Japan and with Turkey in the region demonstrate. Elsewhere in Washington, Central Asia is increasingly being raised in conversations related to the other Quartet countries.

Working in concert

The operations of the Central Asia Quartet could be simple: These could include, for example, annual ministerial-level meetings, small working groups, mechanisms to jointly finance projects, and a joint chamber of commerce. Importantly, the Quartet should maximize Central Asian participation by inviting experts and officials to participate in regular convenings hosted by a rotating chair. Little bureaucracy would be required, and the group would be focused primarily on coordination over institutionalism. Even largely consultative, nonbinding, mechanisms could have major positive impacts.

The financing of projects, especially, could be vastly improved with relatively simple tweaks and coordination. At present, national development finance institutions such as the US International Development Finance Corporation, Japan Bank for International Cooperation, the Export-Import Bank of Korea, Türk Eximbank, and the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development only approve projects that can be certified as advancing their own countries’ strategic or economic interests. This creates gaps when promising initiatives lack an obvious national sponsor.

To address this, the Quartet could establish a streamlined joint certification mechanism that prescreens projects for alignment with each agency’s mandate while standardizing risk-sharing and procurement rules. This would allow projects that nevertheless serve allied objectives, such as mineral supply-chain resilience or Middle Corridor upgrades, to move more smoothly through national approval processes and attract blended cofinancing. Similarly, the Quartet countries could leverage their combined 37 percent shareholder stake in the Asian Development Bank to great effect. The power of the Quartet would come from its simplicity and flexibility, with each member offering something the others cannot.

To maximize the Quartet’s success, it should prioritize minerals, energy, digital security, market access, and connectivity: areas that Quartet members largely agree on, and which ultimately support Central Asian political and economic autonomy. A defense-focused Quartet would likely fare poorly, both due to diverging interests and strategies, as well as the increased likelihood that it would be rejected by Central Asians. Similarly, engaging in cultural diplomacy that focuses on questions of identity, religion, and historical narratives should be avoided: this would risk both fracturing the Quartet and alienating large portions of the diverse region. This is particularly relevant to South Korea and Turkey, both of which leverage ethnic ties to the region to advance soft power presence. The Quartet should nonetheless remain flexible and open to tackling a wide range of issues. For example, as the Quartet matures, it could work to support Turkey and South Korea’s already rapidly expanding Central Asian guest worker programs, which are vital given the importance of Russian remittances to the Central Asian states’ economies.

Of course, implementing the Quartet would not be without its challenges. Despite each country broadly filling a niche, they will still compete with one another in certain areas, such as energy and the automotive industry. Furthermore, all four countries have global priorities that eclipse Central Asia. Though participation in the Quartet is designed explicitly to allow for this, a minimum amount of participation is still required to be successful. Additionally, the Quartet will have to manage its perception carefully to avoid provoking Russia- and China-aligned actors. Similarly, Turkey would have to negotiate a dual approach to the region, considering its prominent role in the Organization of Turkic States, which also has an investment component.

Still, despite the challenges, the creation of the Central Asia Quartet would provide the opportunity for like-minded nations to multiply the effectiveness of their policies. Such a consultative consortium, at minimal political and economic cost, could significantly enhance the efficiency of projects, reduce costs, diversify risk, and share cultural, diplomatic, and technical knowledge. The Quartet would further fit into the model of partnership that Central Asia increasingly searches for: one that is empowering, flexible, opens the door to the West, and is minimally tied to great-power politics. If structured carefully, the Central Asia Quartet could act as a platform for exactly the kind of stable, low-cost, high-reward engagement that Central Asians want and that the United States needs.

Kiran Baez is a research assistant with the Atlantic Council Turkey Program focusing on Central Asia and energy issues. Add him on LinkedIn and X.

The views expressed in TURKEYSource are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Atlantic Council, its staff, or its supporters.

Related content

Explore the program

The Atlantic Council Turkey Program aims to promote and strengthen transatlantic engagement with the region by providing a high-level forum and pursuing programming to address the most important issues on energy, economics, security, and defense.

Image: Rock formations of Ustyurt plateau, Zhabayushkan sanctuary, Kazakhstan. Photo by Максат79, via Wikimedia Commons. Licensed under Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International. https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0/deed.en