US energy firms are returning to Iraq—but politics could undo their fortunes

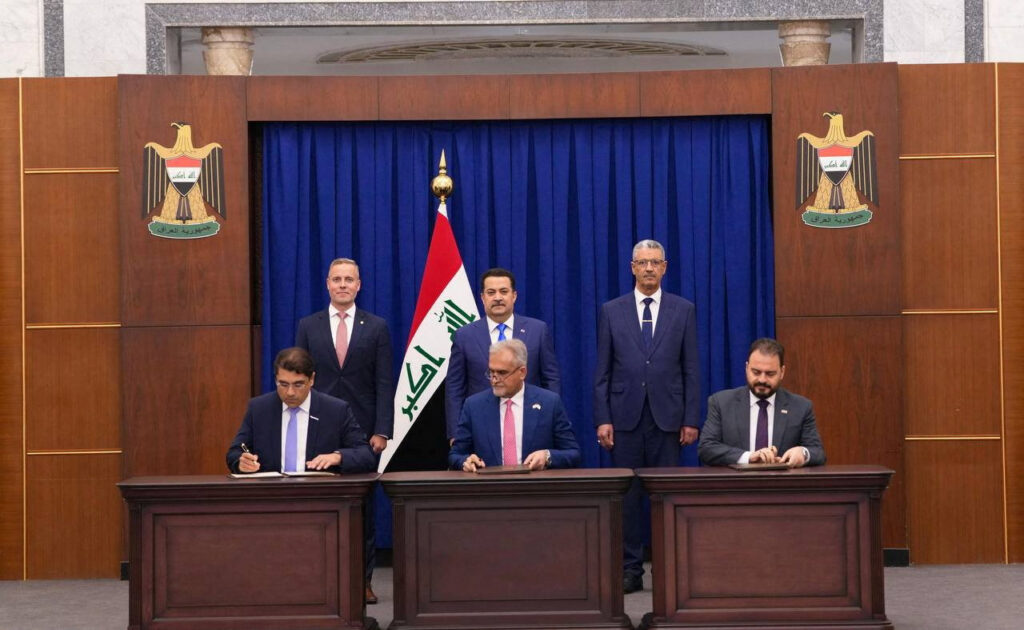

Something unexpected is happening in Iraq’s oil sector. After years of watching from the sidelines as Chinese and European firms dominated, US energy companies are suddenly returning. ExxonMobil, Chevron, HKN, and oil services giant KBR have all signed major deals with Baghdad over the past two months. Meanwhile, in the power sector, GE Vernova is expanding operations.

The timing of this sudden activity is no coincidence. Iraqi Prime Minister Mohammed Shia al-Sudani has discovered what the Kurdistan Regional Government (KRG) learned long ago: Oil and gas deals buy political influence in Washington. He is also hoping that the new deals will buy him US backing for a second term. Thus, at least in part, the latest activity reflects a calculated political dance between Baghdad and Washington.

But it is unclear whether this strategy will bear lasting fruit for either al-Sudani or the oil companies—largely because everything will depend on the outcome of Iraq’s upcoming elections and the messy government formation that will follow. As such, the surge in US company interest represents both opportunity and risk in a country where political calculations can override commercial logic overnight.

Why US firms are suddenly interested

The commercial logic for the companies themselves is straightforward. Iraq offers some of the world’s cheapest-to-produce oil, on a scale that matters to the biggest international oil companies. Few places can match Iraq’s combination of low extraction costs and massive reserves. For companies facing depletion elsewhere and needing to build long-term supply, Iraq represents one of the last great opportunities.

ExxonMobil and Chevron have an additional motivation, as they seek insurance against potential problems in Kazakhstan—where their operations represent sizeable assets for both firms. The current government there is seeking to modify contracts to secure more revenues for the state, and if ExxonMobil’s or Chevron’s ventures in Kazakhstan do face difficulties, Iraqi production could provide crucial backup.

SIGN UP FOR THIS WEEK IN THE MIDEAST NEWSLETTER

But what has really changed the game in Iraq for US firms is the new contracts on offer. The old technical service agreements first introduced by Iraq’s oil ministry in 2009—with their per-barrel fees and limited upside—drove away many US investors, including Chevron, which many in the oil industry had regarded as the partner of choice in postwar Iraq. The recent deals signed by the US firms are different. Companies negotiated directly with Iraq’s oil ministry based on a contractual formula that offers the firms a larger share of overall profits and grants them access to physical barrels of crude that they can trade to their advantage. These are not just better terms; they are fundamentally different agreements that will improve the oil companies’ bottom line.

Baghdad’s political calculus

Commercial considerations only tell half the story. Al-Sudani’s rush to sign deals with US firms over the past few months is fundamentally about political survival, both his own and Iraq’s.

Energy deals, beginning with earlier agreements inked with TotalEnergies in 2023 and BP* in 2024, have been an important element of the prime minister’s ambitious capital investment agenda, which he has used to project the image of an effective administrator among Iraqis as he pushes for a second term in office. With elections fast approaching, he needs more wins to maintain his political momentum, which he hopes to turn into votes.

Al-Sudani’s emphasis on building partnerships with US firms also reveals deeper anxieties. Rising tensions with Washington since the summer over Iraq’s long-standing economic, political, and security ties to Iran—including allegations that Iraqi groups were smuggling Iranian crude—have sparked genuine fear in Baghdad about potential sanctions on Iraq’s oil industry (the country’s economic lifeline and a major supplier to global oil markets). The Iraqi government also fears that Israeli military strikes against Iran-supported Islamist Shia militias in Iraq remain a possibility and that only the United States can keep Israel at bay. Consequently, the prime minister has sought to appeal to US President Donald Trump’s transactional instincts by delivering what his administration often values most: commercial opportunities for US companies.

The strategy is borrowed directly from the KRG’s playbook. For years, the KRG has parlayed relatively minor energy deals to bolster its already outsized political influence in Washington. Al-Sudani is attempting the same maneuver on a grander scale, using major oil contracts as both shield and sword—protection against US economic punishment and leverage for political support. His calculation appears to be that US companies with billions at stake will become important de facto lobbyists for Baghdad in Washington, arguing against policies that might destabilize their investments.

So far, the results of this strategy have been mixed. While the Trump administration has not imposed the harshest measures al-Sudani feared, such as sanctions on senior political figures or on officials in the State Oil Marketing Organization, Iraq has not escaped unscathed as Washington pushes Baghdad to disarm Iran-linked militias. In its latest sanctions move, the US Treasury earlier this month targeted an Iraqi state firm for the first time (al-Muhandis General Company), which Washington alleges is associated with the US-designated group Kataib Hezbollah. The move was a stinging rebuke to al-Sudani, and it embarrassed him domestically in light of his efforts to court the Trump administration. The complicated political and security relationship between the Iran-linked militias and the Iraqi government makes disbanding the armed groups unlikely in the short term, which in turn could lead to more punitive measures if Iraq and Iran hawks in Washington get their way. The oil card, it seems, only buys so much protection.

The election wild card

The upcoming elections in November, and the government-formation circus that is expected to follow, could further complicate things for US investors. Indeed, Iraq’s attractiveness could quickly diminish depending on the outcome.

Al-Sudani’s alliance is favored to win a simple majority, and he is campaigning hard on promises to accelerate his national investment program. Behind closed doors, my sources in Iraq also argue that only he can manage the relationship with Washington. Given his track record so far, a second al-Sudani term would likely mean continued momentum for US investment and perhaps even better terms for US investors.

But Iraqi politics rarely follow simple scripts. Government formation traditionally takes months of horse-trading, as all of Iraq’s major parties seek to reach consensus on powersharing and appointments, paralyzing decision-making in the interim. More importantly, the main Shia Islamist factions—who ultimately choose the prime minister—mostly want al-Sudani gone. It is quietly understood that al-Sudani’s rivals see him as too independent, too powerful, and therefore as a potential threat to their parochial interests and patronage networks. Al-Sudani’s success in centralizing decision-making, and his domestic popularity, have made him dangerous in their eyes. Washington also seems lukewarm about him, despite his commercial overtures, viewing him as too willing to accommodate Iranian interests when necessary.

The electoral math is crucial. Iraqi politics is not about simple majorities but intra-sectarian dynamics. Al-Sudani needs to win not just an incontrovertible majority of “Shia” seats but the right Shia political configuration as well. If al-Sudani fails to win the majority he needs, and his rivals among the established Islamist Shia parties unite against him, a simple majority will not matter. He will be pushed aside in favor of a more pliable and less dangerous alternative.

Al-Sudani’s departure will not necessarily end efforts to attract US investment, but it will remove the most administratively effective post-2003 Iraqi premier. Through personal oversight and a strengthened prime minister’s office, al-Sudani has fast-tracked negotiations with US firms and pushed deals to completion and implementation in ways his predecessors—including previous US favorites—never managed.

This effectiveness is precisely what his rivals fear and want to eliminate. The risk for US companies is getting a new prime minister who embodies the administrative ineffectiveness of past Iraqi leaders, resurrecting the bureaucratic problems that drove many of these same firms away before. Without Sudani’s administrative experience, centralized authority, and political will to push things through, Iraq’s energy bureaucracy risks reverting to its natural state: gridlock punctuated by occasional decision-making.

The bigger picture

Even with increased US investment, Baghdad may find itself at odds with the Trump administration. US strategic interest in Iraq continues to diminish. If oil deals no longer provide political protection, Baghdad’s incentive to prioritize US companies diminishes. Worse, if Washington perceives that the new government in Baghdad is tilting more towards Iran—or even that it simply has the wrong factional balance—the United States could trigger some of the very sanctions al-Sudani has worked to avoid.

If relations do sour, US firms could pay a price. Investment opportunities are not just carrots for Baghdad to offer Washington; they can also become sticks to signal displeasure. While the United States holds most of the leverage, Iraq has shown it is willing to play this game when pushed.

The fundamental reality is that above-ground factors—politics, personalities, and US-Iraq relations—will continue to matter more than geology or commercial terms for US firms in Iraq. Al-Sudani has created a window of opportunity, but windows in Iraq have a habit of slamming shut unexpectedly.

US energy companies returning to Iraq are betting that political winds will remain favorable. They may even be banking on al-Sudani’s survival, continued accommodation between Baghdad and Washington, and their ability to navigate Iraq’s fractious politics. It is a gamble because the next phase of Iraqi politics is uncertain, and elections throw up surprises. The question is not whether Iraq offers attractive opportunities (it does), but rather how the political risks unfold to shape the investment environment.

So, for now, US firms are back in Iraq. Whether their outlook is as propitious a year from now depends entirely on how Iraq’s political drama develops.

Raad Alkadiri is managing partner at 3TEN32 Associates, an international advisory group that assists corporations and governments in navigating the complex political, economic, and social trends that shape the energy sector. Its clients include BP.

Further reading

Tue, Sep 30, 2025

Is the Baghdad-Erbil oil deal a blueprint for settlement—or a stopgap?

MENASource By Victoria J. Taylor , Yerevan Saeed

Whether the oil deal will be a tactical stopgap or a step towards permanent settlement will become known after the Iraq's elections and the year's end.

Thu, Apr 3, 2025

Washington halted the Iraq-Iran electricity waiver. Here is how it’s perceived by Washington and Baghdad.

MENASource By Ahmed Tabaqchali, C. Anthony Pfaff

By making Iranian energy more costly, the United States hopes to incentivize Iraq to diversify its energy sources and reduce its dependency on Iran.

Mon, Jun 30, 2025

Balancing acts and breaking points: Iraq’s US-Iran dilemma

MENASource By C. Anthony Pfaff

The future of US–Iraq relations is neither as dim as it may first appear, nor as promising as one might hope.

Image: FILE PHOTO: A worker walks through the Majnoon oilfield in Basra, 420 km (261 miles) southeast of Baghdad, October 6, 2013. REUTERS/Essam Al-Sudani/File Photo