Many industry stakeholders and policymakers view deep sea mining (DSM) as a panacea for securing sufficient supplies of critical minerals, which are needed for clean energy and defense technologies. In March, the White House issued an executive order promoting mining generally and, in April, followed with a second order to fast-track deep sea permitting and circumvent multilateral regulations of the practice.

However, an analysis of the applicable international and US environmental requirements for DSM reveals that, in practice, the risks to deep sea ecosystems would prohibit DSM from proceeding under current laws.

STAY CONNECTED

Sign up for PowerPlay, the Atlantic Council’s bimonthly newsletter keeping you up to date on all facets of the energy transition.

Why pursue deep sea mining?

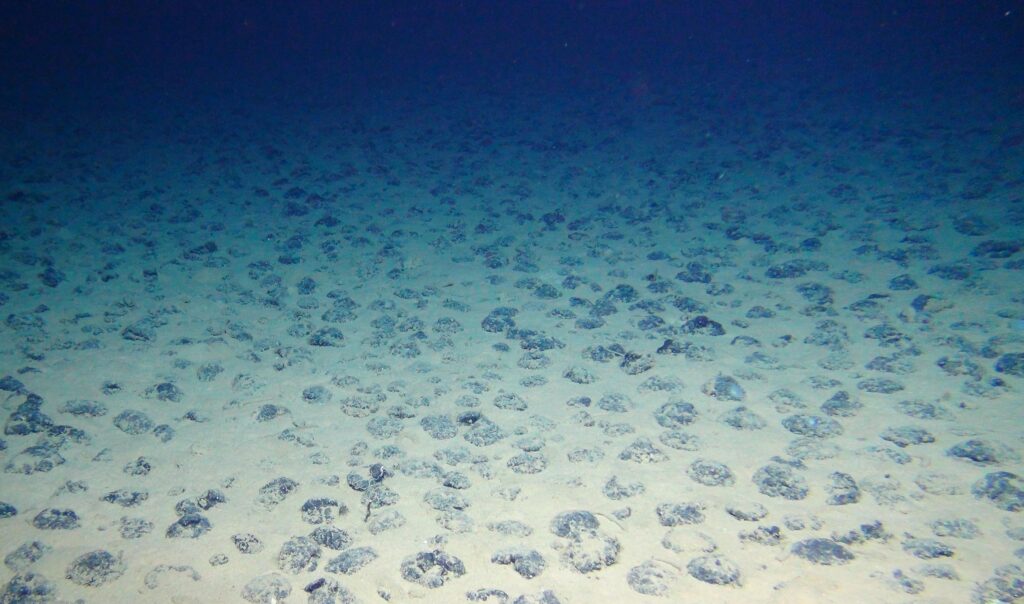

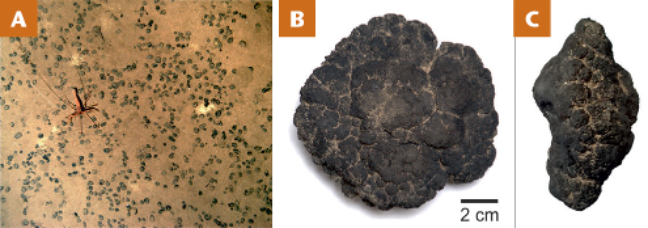

DSM is focused on collecting polymetallic nodules (PMNs) that look like potatoes and contain critical minerals that currently are sourced from mining on land. A patch of the Pacific Ocean called the Clarion-Clipperton (CC) Zone, which covers more than 4 million square kilometers, may hold more cobalt, nickel, and manganese reserves1(p.23) than are available on land.

B. Front of a PMN

C. Side of a PMN

Copyright British Geological Survey, National Oceanography Center © UKRI 2018

What rules govern DSM?

DSM in the CC Zone and elsewhere beyond national jurisdiction is regulated by the International Seabed Authority (ISA) under the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS), to which most United Nations members are parties. The ISA has entered into 15-year exclusive rights contracts for DSM exploration with 17 contractors looking at PMNs in the CC Zone.

The United States is not a party to UNCLOS and cannot sponsor DSM exploration contracts beyond its national jurisdiction, but it and other nations can pursue DSM on their continental shelves, as countries like the Cook Islands are doing. No country is currently mining in the CC Zone, but Nauru is trying.

But the United States has its own applicable laws on DSM: the US Deep Seabed Hard Mineral Resources Act and the US Outer Continental Shelf Lands Act.

So, what do international and US laws say about whether DSM is permissible?

United Nations Convention on Law of the Sea

UNCLOS addresses environmental protection for seabed activities. It directs the ISA to adopt rules for “the prevention of damage to the flora and fauna,”2(Art. 145) to disapprove exploitation where “substantial evidence indicates the risk of serious harm to the marine environment,”3(Art. 162(2)(x)) and to include measures “necessary to protect and preserve rare or fragile ecosystems as well as the habitat of depleted, threatened, or endangered species and other forms of marine life.” 4(Art. 194(5))

International Seabed Authority

The ISA has issued final rules for exploration5(p.4) and draft rules for exploiting6(p.117) deep sea resources. Both regulations require a “precautionary approach” (Principal 15 of the Rio Declaration on Environment and Development) and prohibit activities in international waters that would cause “serious harm,” which both rules define to be any effect which represents a “significant adverse change in the marine environment.”

US Deep Seabed Hard Mineral Resources Act

The United States has its own DSM policy in the Deep Seabed Hard Mineral Resources Act (DSHMRA). This awkward and long-dormant statute prohibits any person under US jurisdiction from exploration or commercial recovery in international waters unless the activity “cannot reasonably be expected to result in a significant adverse effect on the quality of the environment.” That standard is incorporated in regulations. Despite the obvious schism with UNCLOS and objections from the ISA and UNCLOS parties including China and Russia, Canada’s The Metals Company, encouraged by the White House, announced in March that it will apply for a DSHMRA permit to mine in the CC Zone.

US Outer Continental Shelf Lands Act

The Outer Continental Shelf Lands Act (OCSLA) applies to any DSM activities on the 13 million square kilometer US “outer continental shelf”—including Pacific territories where PMNs are found. OCSLA and its regulations have several environmental standards addressing exploration and also requiring mining operations to be “designed to prevent serious harm or damage to … any life (including fish and other aquatic life), property, or the marine, coastal, or human environment.” The potential for DSM in US territory is not an idle consideration. A company named Impossible Metals made an unsolicited request for a lease in 2024 to mine PMNs offshore American Samoa, and has reportedly resubmitted the proposal to the Trump administration, which is likely to be more receptive to the idea.

In sum, the environmental takeaways under these laws are similar:

- Don’t mine if there will be “serious harm” to the environment (UNCLOS).

- Don’t mine if there could be a reasonable expectation the activity will “result in significant adverse effect on the quality of the environment” (DSHMRA).

- Don’t mine if there is “a threat of serious, irreparable, or immediate harm or damage to life (including fish and other aquatic life) … or to the marine, coastal, or human environment” (OCSLA).

Would DSM meet these standards?

Out of concern for environmental impacts of DSM, the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN)—a leading global conservation organization with governmental members, including the United States—approved a resolution in 2020 calling for a moratorium on DSM in international waters. To date, 32 nations have called for a ban or moratorium on the practice.

Studies have shown that the habitats of PMNs teem with exotic and little-understood life. One seminal article estimates that over 6,000 multicellular species occur in the CC Zone, living on and among the PMNs. About 90 percent are probably still undiscovered to science. Each mining operation is likely to remove7(p. 91) PMNs from hundreds of square kilometers each year of operation. If the PMNs disappear, so will these animals, potentially including pink “Barbie” sea pigs and other species that the Natural History Museum of London’s scientists have discovered.

Things go slowly in the deep sea. The PMNs form over millions of years. This is the oldest of old growth—if it is stripped away, the nodules would probably take the same millions of years to come back, if ever.

DSM impacts besides habitat removal include dispersion of animals, noise, and possible oxygen depletion. During DSM testing, contractors primarily use self-propelled collectors that leave tracks and produce sediment plumes with potentially far-reaching consequences8 (p. xii) for the marine environment. One recent study found some small and mobile animals commonly found in sediment everywhere in the CC Zone had re-colonized testing track areas after 44 years, however, large-sized animals that are fixed to the sea floor were still very rare in the tracks, showing little signs of recovery. Impossible Metals proposes to hover and pluck the nodules, but its technology is untested at scale.

The CC Zone is huge—4.2 million kilometers have commercial potential and 3.4 million9(p. 23) are considered particularly attractive for mining. This is an area larger than Alaska, Texas, California, and Montana combined, and the abundance and diversity of life forms vary substantially across it.

What’s the takeaway?

No experienced and objective environmental regulator could reasonably conclude that DSM, as now proposed, would meet the environmental standards of UNCLOS, DSHMRA, or OCSLA.

With new technology, greater understanding of the deep sea environment, and advancements in artificial intelligence, future DSM efforts may be able to selectively harvest PMNs with less impact. But for now, deep sea mining does not pass the environmental tests of the laws that apply.

William Yancey Brown is a nonresident senior fellow at the Atlantic Council Global Energy Center. From 2013 to 2024, Brown was the chief environmental officer of the Bureau of Ocean Energy Management in the US Department of the Interior, where he oversaw the implementation of NEPA.

RELATED CONTENT

OUR WORK

The Global Energy Center develops and promotes pragmatic and nonpartisan policy solutions designed to advance global energy security, enhance economic opportunity, and accelerate pathways to net-zero emissions.

Image: Manganese nodules on the seafloor in the Clarion-Clipperton zone. (Geomar Bilddatenbank, Wikimedia Commons) https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Deep_sea_mining#/media/File:2015-04-14_18-20-14_Sonne_SO239_157ROV11_Logo_original(1).jpg