Lebanon’s fate appears to be irreversibly tied to Syria

Militant group Hezbollah and its allies’ use of Lebanon as a platform to prop up the regime of Syrian President Bashar al-Assad has directly, yet not solely, contributed to the country’s unprecedented economic collapse. With the growing status of Lebanon as a pariah state and its continuing indirect support to Damascus in spite of its dire situation, Lebanon’s fate appears to be irreversibly tied to that of Syria.

Since 2011, Lebanon has been drawn into the regional confrontation between Iran on one hand and Gulf states and the United States on the other. Iran has been supplying Assad with a steady supply of cannon fodder via its proxy Hezbollah, regardless of the Lebanese government policy of dissociation voted in 2012. Hezbollah’s buttressing of Assad, despite the objections of Lebanon’s Sunni population, worsened relations with Arab states, which were already tense since the 2005 assassination of Lebanese Prime Minister Rafik Hariri, for which members of the militant group are being prosecuted.

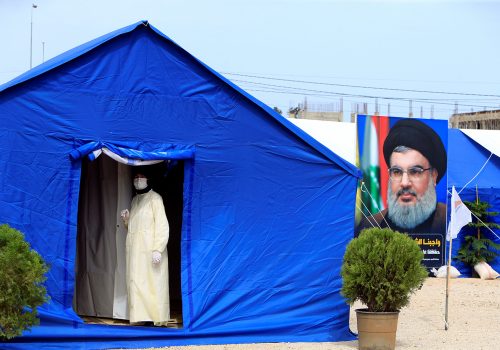

In 2016, Hezbollah Secretary-General Hassan Nasrallah aggravated Lebanon’s relations with the Gulf states where he lashed out at Saudi Arabia in a public statement, saying: “the Saud family will be defeated in Yemen,” a reference to the Saudi-led intervention in the country. Last year, Nasrallah also threatened Riyadh that war with Iran “would destroy you.” Hezbollah remains designated a Foreign Terrorist Organization (FTO) and, in 2019, Washington placed the militant group’s members of parliament on the US Treasury’s Office of Foreign Assets Control (OFAC) sanctions list as well.

With the war winding down in Syria, Hezbollah and its pro-Syrian allies, namely the Amal and Free Patriotic Movements, made sure that Lebanon could act as an economic lifeline for Syria. Over the last few years, Lebanon supplied subsidized oil and flour to Damascus, which further dwindled Lebanon’s already decreasing foreign currency reserves.

Until May, Syrian businesses used Lebanon as a transit center before re-exporting their goods back to Damascus, according to a recent piece by Al-Arabiya. Economists who spoke to me on the condition of anonymity believe that, in 2019, over $2 to $3 billion of subsidized oil imported to Lebanon was smuggled into Syria. Despite the economic collapse and dollar shortage in Lebanon taking place since October 2019 and the government’s compliance with the decision to support basic commodities, diesel and flour are still being smuggled into Syria. Money changers I spoke to also underlined that they were providing currency needs not only for Lebanon but for Syria as well. They are also attributing the large devaluation in the Lebanese pound in March to transfers made to Syria. Mohammed, a currency changer, told me, “We are not talking about a few hundred dollars sent by Syrian workers but of millions—such operations don’t take place in Lebanon without significant political backing.”

The illegal commerce to Damascus has not only shrunk Lebanon’s currency reserves, but worsened already tense relations with Washington, which is expanding the implementation of the Caesar Act to Lebanese businesses operating in Syria. The Caesar Act—named after a Syrian military photographer who leaked some 55,000 pictures of people who were killed and tortured by the Assad regime—aims to sanction those who support Assad and those operating in specific Syrian industries such as construction, energy, and the military. A source close to the Trump administration told me that new measures will be applied with severity on Lebanon if it does not respect the guidelines.

In such a sensitive phase, Hezbollah is facing what it considers to be a western and Arab conspiracy against itself and its axis and is no way willing to modify Prime Minister Hassan Diab’s cabinet, despite its unfortunate track record. Furthermore, the government has failed to pass a much-needed capital law to put an end to an arbitrary control on outflows imposed by banks.

Negotiations with the International Monetary Fund (IMF) have also gone nowhere and over half the population is now living under the poverty line. The Diab cabinet was appointed in January by a coalition dominated by Hezbollah and the Free Patriotic and Amal movements—two allies the militant group cannot do without even given their corruption allegations. And, although the cabinet includes largely respected technocrats, such as Ghazi Wazni and Demianos Kattar, their participation has shown that they have little freedom to operate from the Diab government’s primary political backers.

Hezbollah’s priority remains outwardly directed; it will continue to adopt more radical stances to be able to manage its regional agenda. Yet, with hope for any solution dimming every day, and as Lebanon and Syria’s fate becomes increasingly intertwined, the situation will grow more desperate. For the foreseeable future, at least, Lebanon’s fate will remain squarely in Iran’s ‘axis of resistance’: a pariah state without any immediate prospect of genuine reform.

Mona Alami is a nonresident senior fellow with the Atlantic Council’s Middle East programs.

Image: A money exchange vendor counts Lebanese pound banknotes at a currency exchange shop in Beirut, Lebanon June 17, 2020. REUTERS/Mohamed Azakir