Lebanon’s economic recovery plan will only repeat past failures

On April 30, Lebanon’s new Prime Minister Hassan Diab revealed his economic recovery plan and, along with his political allies, touted it as the panacea for Beirut’s financial woes. Since then, his government has been locked in negotiations with the International Monetary Fund (IMF), whose assistance—along with other foreign aid—is posited as the necessary precondition for jumpstarting economic recovery in the plan. But the IMF remains skeptical. Its spokesman Gerry Rice has said it is “premature to talk about any… financing right now.” Some of Lebanon’s negotiators with the IMF share that skepticism, two of whom—Henri Chaoul and Alain Bifani—have resigned in protest over Beirut’s obstinate resistance to genuine reform—and rightly so.

Diab’s plan simply won’t suffice. Its remedies are either incomplete or premised on repeating past failures. Indeed, Lebanon has few, if any, tools to restore sustainable growth and those are certainly not the routes outlined in the plan.

Decades of corruption, waste of public funds, and financial mismanagement have ruined Lebanon’s economy. Rather than create productive sectors, successive Lebanese governments have bet on high-end tourism, luxury real estate, and expatriate remittances to remain afloat since 1990. But even prior to the coronavirus pandemic, its bloated bureaucracy, poor infrastructure, and security concerns drove away tourists and investors.

Instead of funds trickling down—as the government had hoped—this flawed economic model created wage stagnation and high basic living costs. Meanwhile, partisan politicians squandered or stole foreign aid intended for upgrading Lebanon’s vital infrastructure—like electricity, water, waste management, or public transportation—and doled out public jobs—by far the country’s largest sector—to their cronies.

Meanwhile, Beirut consistently overborrowed and overspent. By 2018, Lebanon’s per capita GDP shrunk to $8,269. Coupled with anemic growth—as low as 0.2 percent—its public debt ballooned to the world’s third highest at 170 percent of GDP. This year, per official figures, inflation will reach 53-55 percent, as the economy shrinks by more than 12 percent. The Lebanese lira, once pegged at 1,500 to the dollar, has lost over half its value, pushing almost half of the Lebanese people into poverty.

Diab’s promise that his plan will remedy this dysfunction and restore economic growth by 2024 is unlikely.

The plan’s figures are based on an incorrect exchange rate of 3,500 lira to the dollar—an exchange rate that Beirut has lost control over. It has been fluctuating between the official 3,850 rate—up to nine thousand lira to the dollar as of the date of this publication—on the black market. The plan also depends on speculative funding sources, like the Lebanese diaspora—without providing any estimated figures or how Lebanon intends to attract their dwindling remittances—and approximately $21 billion in foreign aid and IMF assistance, which might never come.

Additionally, the plan’s avenues for economic recovery—tourism, a knowledge economy, banking, and agriculture—are non-starters.

Tourism, once the country’s economic centerpiece, has languished due to domestic, regional, and international turbulence that’s unlikely to subside in the near future. Meanwhile, other countries are increasingly edging out Lebanon as the Middle East’s luxury entertainment, world heritage, and summer tourism hubs. The country has replaced virtually all that is culturally unique or environmentally attractive with edifices of hollow opulence, decreasing Lebanon’s chances of a touristic revival.

Reviving Lebanese tourism is based on the unsubstantiated hope that Lebanon’s private sector will restore this infrastructure to its heyday. Centering the economy on tourism would also repeat Lebanon’s past mistakes, as it largely benefited only specific segments of the Lebanese populace and economy, particularly luxury retailers concentrated in urban, coastal areas.

Diab’s reform plan also calls for establishing a knowledge economy as “the future for… Lebanon.” However, the country ranks as one of the world’s most corrupt and one of the hardest to do business in. Additionally, Lebanon’s lack of basic business infrastructure—like twenty-four-hour electricity or modern internet speeds—domestic instability, and the constant threat of war are insurmountable deterrents to serious foreign investment.

Lebanon’s corruption and US anti-Hezbollah financial sanctions would also prevent Beirut’s return as the region’s banking hub. In fact, Beirut’s finance minister predicts that its number of banks will be halved. Lebanon also can’t become a regional agricultural net exporter, as only 12 percent of its small territory remains suitable as arable land, having declined for decades due to unconstrained construction and illegal well-digging. Oil and gas, on which Lebanon once pinned its hopes, also hold no promise, as off-shore exploration has revealed that Beirut lacks commercially viable quantities of these natural resources.

Moreover, the areas where the plan is silent on speaks volumes about Beirut’s lack of will for genuine reform. Perhaps, as a concession to the feudalist forces backing Diab, his plan fails to redress the sectarian factionalism and chieftains—including Hezbollah’s shadow state and army—that have drained Lebanon’s vitality or how to recover the funds they stole.

As a corollary concession, the plan leaves Lebanon’s bloated public sector—one of the country’s major sources of corruption, stagnation, and economic drain—unaltered. Beirut’s arcane bureaucracy and overly generous governmental employee benefits have perpetuated the rule of Lebanon’s feudal lords, who dole out favors and jobs to secure street support and votes. While this sector balloons the country’s budgetary deficit by employing one-third of the Lebanese people, it still fails to provide functioning basic public services, like twenty-four-hour electricity, clean water, and infrastructure.

Lebanon’s resistance to genuine reform is perhaps most prominently typified by Hezbollah, which has been signaling its readiness to veto any IMF deal that “imposes terms on Lebanon.” The group has been prodding Beirut to instead “turn eastward” to revive its economy, looking at countries like Syria, Iran, Russia, and, particularly, China—a recommendation which is gaining traction within the Diab government. Beijing’s aid and investment may provide a quick, temporary fix to many of Lebanon’s economic woes. However, Lebanon will inevitably relapse into economic chaos precisely because Chinese funding won’t hinge on Beirut enacting the necessary reforms to build a sustainable economy.

Moving forward, the IMF and international donors must continue taking a hardline stance vis-à-vis disbursing aid to Lebanon. In the short term, that means denying Beirut aid until it implements genuine and sweeping reforms.

However, in the past, Lebanon has limped along, and even prospered, on superficial or short-term solutions (as was seen during Beirut’s “golden years” between independence and the 1975 civil war), before the centrifugal forces inherent in its flawed sectarian system pulled the country apart.

Therefore, international oversight must continue in the medium term. IMF and international aid —including from the 2018 CEDRE conference—must be disbursed to Beirut in tranches in return for results and a supervised, transparent privatization process of state-owned companies to exclusively foreign bidders. Doing so would prevent the resurgence of the country’s sectarian political oligarchs through domestic shell corporations and, perhaps, permanently cripple their political power by making Lebanese citizens less dependent on them for employment.

But Beirut will require long-term supervision to sustain this progress. Any future aid and investment must be conditioned on sustaining tangible progress and ensuring that Lebanon’s corrupt sectarian forces, which are unlikely to be eliminated in the foreseeable future even by the most genuine of reforms, will not lead to its relapse. Absent such a strict, multi-tiered process with constant supervision, IMF and donor countries will be throwing their money away as Beirut’s corrupt system persists, which in turn will see Lebanon seeking financial assistance and foreign loans, again.

David Daoud is a research analyst at United Against Nuclear Iran (UANI) on Hezbollah and Lebanon. Follow him on Twitter: @DavidADaoud.

Paul Gadalla is a former Beirut-based journalist who also worked in communications at the Carnegie Middle East Center in Lebanon. Follow him on Twitter: @BoulosinDC.

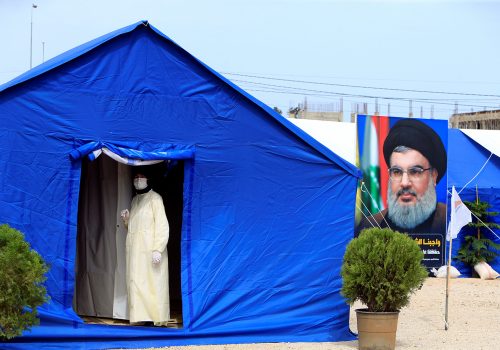

Image: A man rides a motorbike past a poster depicting Lebanon's Hezbollah leader Sayyed Hassan Nasrallah, near Sidon, Lebanon July 7, 2020. REUTERS/Ali Hashisho