Amidst the pandemic, Hezbollah buries fighters killed in Syria

On March 19, Lebanon closed its borders, including the land crossing with Syria, as it locked down to prevent the spread of coronavirus.

A fortnight later, on April 2, the family of Husayn al-Sayyed Husayn buried the young man’s remains in the Louaizeh village graveyard in south Lebanon.

At first, the two events appear unconnected. But Husayn was an 18-year-old Hezbollah fighter killed in Syria on November 2013, where the Iran-backed Lebanese militant group fights in support of the Bashar al-Assad regime.

Despite the official border closure, Husayn’s remains are among those of at least six Hezbollah combatants, as well as one commander, killed up to seven years ago and recently brought back from Syria.

A Hezbollah media official said the remains were returned from Syria “before coronavirus,” but was not able to provide a specific date. The returns were widely publicized on pro-Hezbollah news sites and Facebook pages after the lockdown, including a picture of three of the bodies wrapped in Islamic green cloth before their burial. Four sources close to Hezbollah, including a fighter who returned from Syria in January, said the Lebanese border was not closed for the party’s use.

“The borders are closed to you only,” said a Hezbollah fighter from Beirut, who went by the name Hassan, with a smile.

The sources confirmed details of the returns, most of which were the remains of fighters killed in 2013 in battles with Syrian rebels in the Damascus suburb of Eastern Ghouta. They painted a picture of exhumations in areas recaptured by pro-Assad forces and bodies of Lebanese fighters still missing in Syria.

“These guys were missing, they were martyred seven years ago, and today they returned, because they were all missing, disappeared. [The battle in] Syria has nearly finished,” said an administrator of a pro-Hezbollah WhatsApp news group, who went by the name Abo Ali.

“The Syrian Arab Army and Hezbollah search for the bodies in Eastern Ghouta. There are groups tasked with this job,” said a resident of south Lebanon supportive of Hezbollah and familiar with the returns. “Bodies are still missing in Eastern Ghouta, rural Aleppo, and just maybe a couple in the desert of eastern Syria. They are working on finding them all. Some are swapped with the rebels in deals. . . Some are found by digging in possible areas and asking locals, like recently.”

And it’s not just the remains of Hezbollah fighters killed years ago that are returning to Lebanon. Multiple additional combatant deaths have been reported by media outlets close to the party since the COVID-19 lockdown, pointing to its continued engagement in military combat and training activities.

They include Jad Yasin Sufan from south Lebanon, whose death was announced on July 10, and whose body was paraded at the Sayyida Zaynab shrine south of the Syrian capital Damascus, before being returned to Lebanon. The tomb is a key pilgrimage site for Shia Muslims and its protection was one of the main reasons Hezbollah used to justify its military intervention in Syria more than seven years ago.

The specific circumstances and locations of these recent deaths are unclear, with funeral reports simply stating that each died “carrying out his duty of jihad.” Hezbollah operates militarily in Lebanon and Syria and has sent trainers and commanders across the region.

Lebanese journalist Ali Amine, who edits the Al-Janoubia news site, said that the wording in the recent death notices pointed to them happening in Syria. “The official obituary of the Islamic resistance talks about a “martyr of the holy defense and the knights of Zaynab,” which is an affirmation of him dying in Syria,” said al-Amine. “Zaynab denotes the shrine of Sayyida Zaynab in Damascus.”

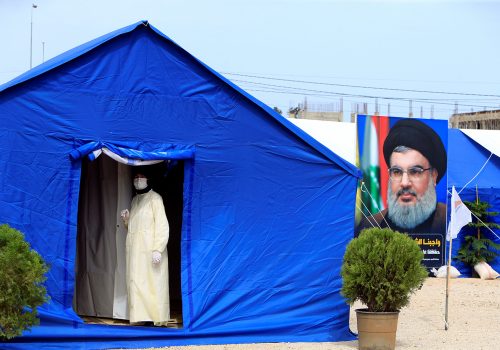

The fighters’ remains are returned to Lebanon in ambulances belonging to Hezbollah’s Islamic Health Unit, according to three sources close to the party. The same health unit has also been deployed in the Islamist party’s coronavirus response by way of disinfecting public spaces, preparing to transport COVID-19 cases to hospitals, and carrying out public awareness campaigns. Analysts say the pandemic has provided an opportunity for Lebanon’s political parties, such as Hezbollah, to try to prove themselves as service providers, especially after 2019’s widespread anti-establishment protests.

Sources gave differing accounts of the routes used to return bodies from Syria. Hezbollah uses an official crossing, according to one, while another said they rode on “special routes” away from the border checkpoint.

For the past month, the Lebanon-Syria border has been open two days a week for Lebanese citizens in Syria wishing to return home, but there was “no information” on the return of the Hezbollah fighters’ corpses, according to a spokesperson for the Lebanese General Security, which controls the official border crossings.

“Hezbollah deals with the remains of fighters killed in action itself and has specialists in its Islamic Health Unit to carry out DNA tests to confirm their identities,” claimed the Hezbollah media official. “It’s in the hands of the Islamic Health Unit.”

Lebanon’s Ministry of Public Health was unable to provide information on standards and stipulations for cross-border repatriations of human remains.

Funerals for the returned fighters—which are organized and funded by Hezbollah—have been affairs inconsistent in social distancing. Video footage from the funeral procession of Bilal Hatoum, whose remains were returned from Syria’s Eastern Ghouta in early April, showed mask-wearing attendees socially distancing from each other at times. But at others they gathered close around his coffin, draped in a yellow satin Hezbollah flag.

In an interview in April, Hassan, the Hezbollah fighter recently returned from Syria, played down any impact of the pandemic on the Party of God.

“The coronavirus did not affect Hezbollah. Battles have diminished somewhat. Whoever was here stayed here and whoever was there [in Syria] stayed there,” he said. “There are breaks. When the situation is stable, we come back [to Lebanon]. When the situation becomes tense, we go to Syria.”

Lebanon and Syria have both reported relatively low coronavirus cases and death numbers: Beirut imposed a lockdown early on and, as of July 13, had recorded 2,334 cases and thirty-six deaths for a population of around six million. Syria’s case numbers remain in the hundreds, although observers have raised doubts about their accuracy.

In Syria, Hezbollah has trained and fought alongside Afghan, Syrian, and Iranian commanders and militias, while gaining extensive battlefield experience.

Offensives in Syria have become part of the group’s narrative of military victories. In May, Secretary-General Hassan Nasrallah said that, “Syria emerged victorious at the end of a universal war,” claiming that the party entered the conflict in part due to a threat to Palestine. He drew together the multiple conflicts in which Hezbollah has been or is involved into a narrative of one war against hostile enemies, often characterized as a “US-Israeli plot.”

Although battle intensity has lessened in many parts of Syria, Hezbollah combatants will likely remain deployed in the country, especially in the Lebanese border areas around AlQusayr, where it has reportedly built up weapons stocks.

While the cross-border body traffic is less frequent than it once was, the recent returns show that even a global pandemic will not prevent the Party of God from military deployments in both Syria and Lebanon.

“They have the same importance,” said the fighter Hassan, when asked to compare battles in Syria with confronting Israel in his home country. “There is no difference between them. It is the same project.”

Lizzie Porter is a freelance journalist based in Beirut, Lebanon, focusing on Shia politics and religion, Lebanon, Syria and Iraq. Follow her on Twitter: @lcmporter.

Image: Hezbollah fighters' graves at the Garden of Lady Zeinab cemetery, which is reserved for combatants, in Beirut's southern suburbs