While sub-Saharan Africa has enjoyed an average economic growth of over 5 percent since the turn of the century, a recent International Monetary Fund (IMF) estimate has sparked worries of a continent-wide slowdown. The report estimated that Africa’s combined gross domestic product (GDP) has grown by a mere 1.5 percent rate in 2016, the continent’s worst performance in more than twenty years. Although this figure is still to be confirmed by the IMF, it comes as a blow to the widely-touted “Africa Rising” narrative that has often been employed by government and business leaders in Africa to incentivize foreign investment.

While sub-Saharan Africa has enjoyed an average economic growth of over 5 percent since the turn of the century, a recent International Monetary Fund (IMF) estimate has sparked worries of a continent-wide slowdown. The report estimated that Africa’s combined gross domestic product (GDP) has grown by a mere 1.5 percent rate in 2016, the continent’s worst performance in more than twenty years. Although this figure is still to be confirmed by the IMF, it comes as a blow to the widely-touted “Africa Rising” narrative that has often been employed by government and business leaders in Africa to incentivize foreign investment.

The reality remains that the growth which catalysed the idea of “Africa Rising” was largely due to a generally favorable global economic environment. Thus, while stronger monetary and budget policies, along with an improved macroeconomic situation, helped African countries weather the 2008-09 global economic crisis, a recent sharp fall in the global price of commodities, and a decrease in global demand, among other factors, have illustrated many African countries’ vulnerable endogenous capacity to sustainably deliver high economic growth rates. However, these external factors do not influence all African countries equally. Indeed, a deeper analysis suggests that the aggregate growth figure hides the development of a multi-layered growth, with most of the region’s net importers of commodities doing much better than their resource intensive counterparts.

In fact, although as many as twenty-three of the continent’s fifty-four nations are under severe economic strain, the region’s biggest oil producers face particularly bleak short-term prospects. Hampered by internal political strife, droughts, the emergence of non-state terrorist actors, and the fall in demand for natural resources, Nigeria and Chad are mired in recessions. Angola, a regional powerhouse whose oil production represents 95 percent of exports and 75 percent of the state’s fiscal revenue, will barely avoid a downturn this year.

Other resource exporters such as South Africa, which recently wrestled the title of Africa’s biggest economy back from Nigeria, are also undergoing economic stagnation. The prices of commodities produced by the country, having followed the downward global trend, combined with the resurgence of chronic bad governance and outright corruption have eroded investor confidence and led to a significant drop in the rate of foreign direct investment.

However, it would be a mistake to assume that sub-Saharan Africa’s recent growth was only due to the last decade’s commodity boom, or to overstate the long-term importance of these muted IMF growth figures. In fact, many African countries have continued to modernize their economies through the implementation of sound policies, and still managed to sustain steady growth rates in 2016.

Indeed, this more heterogeneous group of economies is predicted to see its collective GDP increase by 5.5 percent, just below the 6 percent rates it averaged during the last decade. Despite many challenges such as terrorism, droughts, and pandemics, these growing countries have also done much to diversify their economies. These countries fall into three distinct groups.

First, the much poorer countries of the group focused on consolidating the basics such as security and good governance, while trying to improve the productivity of the agricultural sector. Mali, for example, whose growth is thought to have hit 6 percent, despite recent terrorist attacks on its capital Bamako, allocates almost 45 percent of its budget to improving state capacity, bolstering its military capabilities, and subsidizing its agriculture.

Similarly, another desperately poor yet promising nation, Ethiopia, capitalized on low labor costs, business friendly regulations, and strategic public investments in new industrial parks to boost its exports and drastically reduce its poverty rate. This is the reason why the United Nations Industrial Development Organization (UNIDO) selected the East African nation, along with Senegal to be the first recipients of their ambitious Inclusive and Sustainable Industrial Development (ISID) program, which aims to eradicate poverty and create prosperity in developing countries through industrialization.

Second, “economies in transition” as identified by the McKinsey report, Lions on the Move, are characterized by having a burgeoning manufacturing industry as well as an agricultural sector representing a considerable share of the national GDP. Such countries, having spent the last few years consolidating their internal political climates and improving business environments through reforms such as changes to the tax code or facilitating land access, were able to focus the bulk of their budget on making strategic investments in much-needed infrastructure and energy projects.

Indeed, nations like Senegal and Côte d’Ivoire, for example, owing much to their responsible macroeconomic management, are expected to be among the region’s fastest growers when official 2016 GDP figures are confirmed later this year. This success is fully understandable when contextualized by both the Emerging Senegal Plan and Cote d’Ivoire’s National Development Plan, which preconize prudent fiscal management, while encouraging structural transformations of the economy and improving the private sector’s position in areas such as agriculture, manufacturing, education, and services.

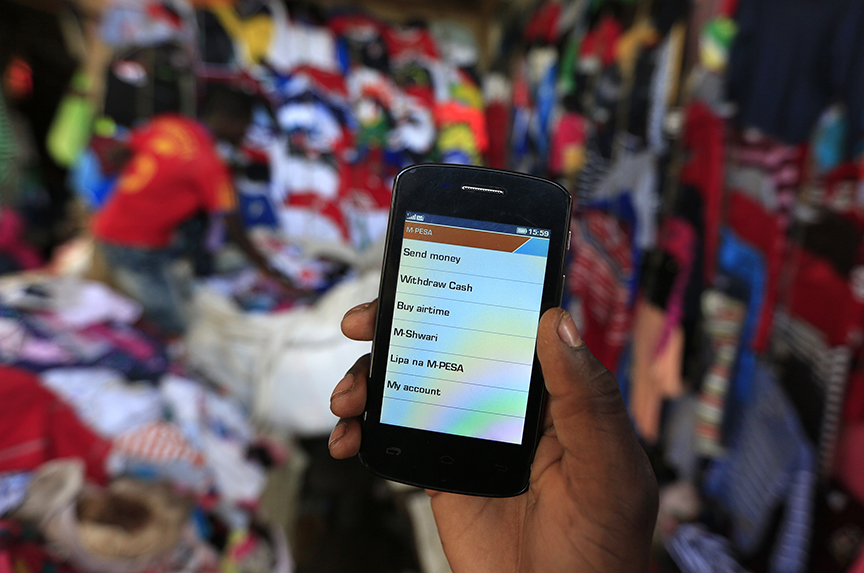

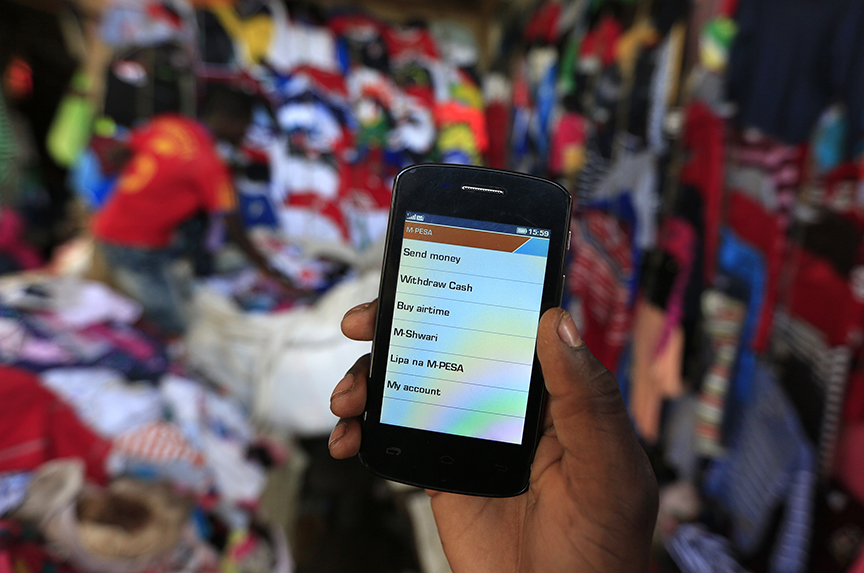

Finally, Kenya, whose growth is also projected at 5.9 percent, exemplifies sub-Saharan Africa’s more advanced economies. Kenya was able to take full advantage of its young population as well as the country’s bustling technology, banking, and insurance industries. Today, for example, Kenya’s capital city of Nairobi, often referred to as Africa’s Silicon Valley, is home to many of the continent’s most innovative technology-based initiatives such as M-Pesa, M-Farm, ICow, and Ushahidi whose solutions are being replicated all across the world. The private sector’s involvement was also complemented by strong public investments and the many government-paid initiatives in the mould of the National Youth Service (NYS), a program aimed at reducing unemployment among the restless youth population.

It is, however, no coincidence that most of the countries that are doing well economically belong to the models of regional integration that are the East African Community (EAC) and the West African Economic and Monetary Union (WAEMU). These trading blocs have, through the promotion of free trade and harmonization among member states of carefully benchmarked policies, considerably improved their regions’ competitiveness and attractiveness to investors. Yet, despite the continent’s many “success stories,” economic growth is unlikely to spill over to commodity exporters anytime soon, as current trade among countries in Africa only makes up 14 percent of total trade, a relatively low percentage compared to the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) and the European Union (EU) whose intra-regional trade amounts to 25 percent and 60 percent, respectively.

There is, however, evidence that governments in the region are moving to address the significant lack of intra-regional trade. Beyond EAC and WAEMU, SSA is home to other trading blocs boasting free movements of goods and people, three of which have recently formed the African Free Trade Zone (AFTZ). After the 2015 Africa Union Summit, there is great hope that this agreement could soon be extended to all of the continent’s fifty-four states, which should boost the continent’s trade figure.

Overall, it is clear that significant parts of sub-Saharan Africa remain on an upward trajectory. Today, almost half of the countries on the continent are performing well and taking considerable steps toward diversifying their economies. Yet, most of sub-Saharan Africa’s biggest economies underperformed last year, having failed to implement enough game-changing reforms during the commodities boom of the last decade. Going forward, the onus is on the continent’s main resource exporters to prove that 2016 was not the year when the continent’s carefully crafted “Africa Rising” narrative started unravelling.

Mayécor Sar is an Atlantic Council Millennium Fellow and a policy adviser at the presidential delivery unit in the Office of the President of Senegal. You can follow him on Twitter @Mayecorsar.

Image: A man showed his M-Pesa mobile money transaction page at an open-air market in Kibera in Kenya’s capital Nairobi on December 31, 2014. M-Pesa is a mobile phone-based money transfer, financing, and microfinancing service. (Reuters/Noor Khamis)