Beyond tariffs: Building a win-win relationship between the US and Iraq

Iraq was among the countries that received a letter from US President Donald Trump on July 9th advising its prime minister that Baghdad’s trading relationship with Washington was far from reciprocal—and thus its exports to the United States would be subject to a 30 percent tariff starting August 1.

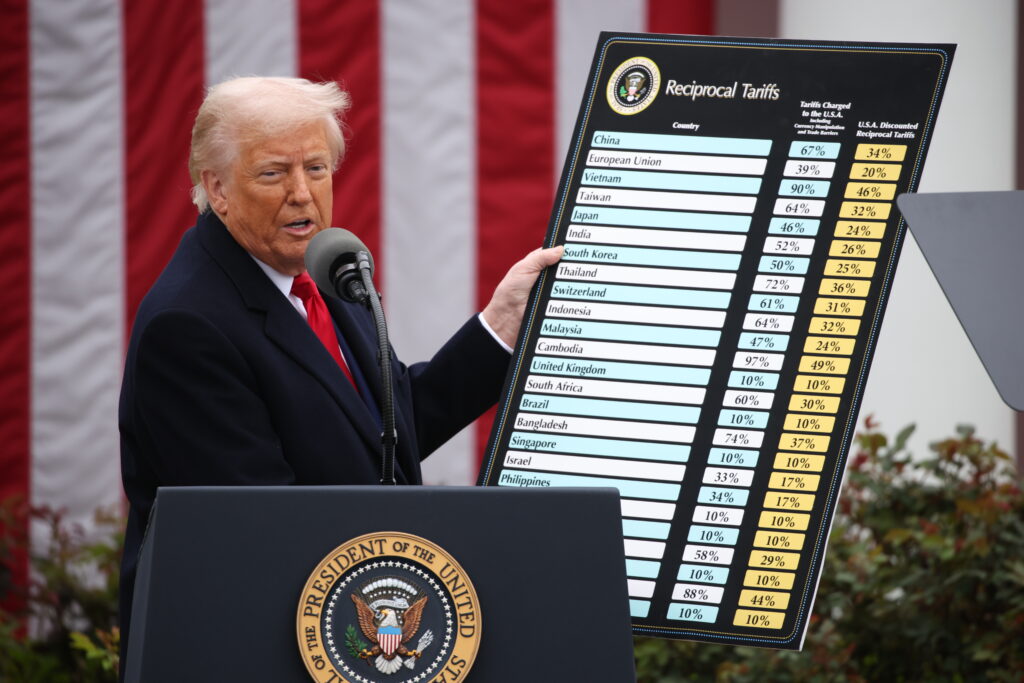

This is lower than the initial rate of 39 percent that the Trump administration announced on “Liberation Day” back in April, but higher than the revised 10 percent base rate that applied to all countries when the Trump administration paused “Liberation Day” tariffs for ninety days, allowing room for negotiations that expired in July.

But the US trade deficit with Iraq is primarily a function of Iraqi oil exports, which are exempt from reciprocal tariffs. Thus, the first 39 percent rate, the 10 percent temporary rate, or the new 30 percent rate have no direct implications for the calculation. However, there will be indirect impacts resulting from lower oil prices, due to the expected decline in global oil demand that is likely to follow the potential adverse effects of the tariff on global trade.

This piece will review the mechanics of the tariffs imposed on Iraq, a brief history of the trade between the two, and policy responses for a win-win relationship between Iraq and the United States—particularly with respect to the US-Iraq Strategic Framework Agreement, which is a key framework for the evolving relationship between the two towards one that is focused on political, economic, cultural, and security ties.

SIGN UP FOR THIS WEEK IN THE MIDEAST NEWSLETTER

The mechanics of the tariffs

There is no public data on how the Trump administration decided on the 30 percent tariff rate for Baghdad, nor is there information on Washington’s assessment of their expected effect on its trade deficit— apart from Trump’s assertion that they are “far less than what is needed to eliminate the Trade Deficit disparity we have with your country,” he wrote in a July letter to Iraq’s Prime Minister Mohammed Shia’ al-Sudani.

Nevertheless, there is enough data to see how the initial 39 percent was calculated. On Trump’s so-called “Liberation Day,” the US Trade Representative (USTR) announced its rate formula, in which many variables canceled each other out. Thus, the formula effectively calculated the trade deficit with a country, divided by imports from that country. Then, the US reciprocal tariffs are 50 percent of that result in order to balance the deficit.

The US-Iraq trade relationship was estimated at approximately $8.8 billion in 2024, comprising Iraq’s exports to the United States of $7.4 billion (mostly oil) and the United States’ exports to Iraq of $1.4 billion—excluding re-exports of $0.3 billion through the United States. The top five US imported goods to Iraq account for 70 percent of the total, including cars at 39 percent, machinery at 16 percent, pharmaceuticals at 8 percent, electrical and electronic products at 8 percent, and optical, photographic, technical, and medical apparatus at 7 percent. However, the data does not capture all of the US exports of these same products that come via third countries in the region by Iraqi importers. There are no data on the value of these exports, as they effectively enter Iraq as exports from a third country; thus, it is not possible to identify them as US products.

With these numbers taken into account, the US-Iraq trade deficit—at least until Trump tariffs take effect—is worth about $5.8 billion, so its tariff and non-tariff barriers are 78 percent (5.8/7.4 = 78 percent), and thus, according to the Trump administration’s calculus, the reciprocal tariff rate of 39 percent (78/2= 39 percent) is correct.

A brief history of Iraq-US trade

In looking at the trading relationship this piece will consider Iraq oil exports in terms of barrels per day (bpd) and not in their amount in dollars in any given year, as changes in oil prices can alter the numbers meaningfully leading to false conclusions—for instance oil exports of 200,000 bpd, at $30 bpd lead to $2.1 billion in export revenues yet could lead to $4.2 billion in export revenues if oil prices were $60/bbl, but the barrels exported are the same.

The US exports to Iraq have been relatively small, averaging $1.4 billion a year between 2012 and 2024, with trade declining from $2 billion in 2012 to $1.4 billion in 2024; while overall exports to Iraq have almost doubled in the same timeframe. However, this is not a function of a declining relationship or a decline in demand for US products, but rather the evolution of Iraq’s economy towards a consumer-driven economy, in lockstep with the end of years-long conflicts. Iraqis are also increasingly importing the same consumer goods from China that the United States, Europe, and other regional consumers are importing. Crucially, this is not a function of tariffs or non-tariff barriers on US exports. As the International Monetary Fund (IMF) notes, Iraq has a low effective tariff rate, estimated at under 1 percent in 2023, which is significantly lower than in other Middle East and North Africa countries from 2012 to 2023.

Between 2012 and 2024, Iraq’s total oil exports grew by 39 percent, while its exports to the United States declined by 64 percent. However, this is not a function of a declining relationship, but rather a result of two factors specific to the United States. The first is that US oil consumption has been modest during this period, increasing by 8 percent, while its oil imports have decreased by 23 percent during the time frame. This is a function of the second US-specific factor, that is, the emergence and rapid expansion of its shale oil industry. This fundamentally altered the profile of the United States as an oil importer, with imports as a percentage of its oil consumption declining from 49 percent in 2012 to 35 percent in 2024.

Policy Implications

The promising aspect of Trump’s letter—that the tariffs are subject to revision and the evolving relationship with the United States—presents an opportunity that Iraq can seize to build up crucial aspects of the US-Iraq Strategic Framework Agreement.

Iraq can accomplish this through developing both its economic energy relationship with Washington, as well as securing Iraq’s energy independence by diversifying its sources of gas exports away from its dependence on Iranian gas imports. These go much beyond any specific Iraq trade policy with the United States, given its very low effective tariff rate of around 1 percent (earlier), or any Iraqi efforts or measures to increase US imports for its Public Distribution System (PDS) such as imports of rice, and grains—as crucial as these are for Iraq to pursue.

This can be done through a mega-energy deal with US companies. Such a deal should encompass multiple interlinked components, and unfold over multiple years; it can be larger and more strategic than, but along the same lines as, the $27 billion energy deal signed with TotalEnergies in mid-2023, or the $25 billion energy deal signed by BP in early 2025.

The framework of this mega-deal could include interlinked deals between multiple US companies, covering four sub-components. The first sub-component is alternative gas imports, to meet its demand for gas for power generation, through imports of US Liquified Natural Gas (LNG), in addition to its recent deal for pipeline gas imports from Turkmenistan.

This opens up and leads to the second subcomponent, which is the significant infrastructure development needed to develop Iraq’s LNG infrastructure by US companies. The sourcing of LNG from the United States and building LNG infrastructure can be complemented by the third sub-component, which involves increasing domestic gas production sources by capturing large amounts of flared gas using US technology and companies.

The gas produced from these three subcomponents leads to the fourth subcomponent, which effectively uses this gas for electricity generation to meet Iraq’s need to close the gap between supply and demand of electricity. Thus, the fourth sub-component completes the first three, through the upgrading and development of Iraq’s electricity grid infrastructure by US companies such as GE Vernova. For all these to happen smoothly, Iraq needs to facilitate access and secure investments from US companies across all aspects, especially in relation to any tariff and non-tariff obstacles, irrespective of its current low effective tariff rate.

Not only does this create the first large visible economic and energy aspect of their Strategic Framework Agreement, but the successful implementation of these four subcomponents can have substantial positive implications for Iraq’s economy, which in the process creates more investment and trade opportunities for US companies in Iraq’s evolving economic journey.

Ahmed Tabaqchali is a nonresident senior fellow with the Atlantic Council’s Middle East Programs. He is an experienced capital markets professional with over 25 years of experience in the US and MENA markets, and serves as the chief strategist at the AFC Iraq Fund.

Further reading

Mon, Jul 7, 2025

Unpacking Iraq’s Federal Supreme Court chaos

MENASource By

Regardless of the reasons behind initial mass resignations, the ongoing uncertainty surrounding the Supreme Court is serious.

Mon, Jun 30, 2025

Balancing acts and breaking points: Iraq’s US-Iran dilemma

MENASource By C. Anthony Pfaff

The future of US–Iraq relations is neither as dim as it may first appear, nor as promising as one might hope.

Thu, Apr 3, 2025

Washington halted the Iraq-Iran electricity waiver. Here is how it’s perceived by Washington and Baghdad.

MENASource By Ahmed Tabaqchali, C. Anthony Pfaff

By making Iranian energy more costly, the United States hopes to incentivize Iraq to diversify its energy sources and reduce its dependency on Iran.

Image: This picture shows a chimney at an oil field in the Shekhan district near the Kurdish city of Dohuk in the Kurdistan Region of Iraq. Several oil fields in the Kurdistan Region were targeted by explosive-laden drones between July 14th and 17th, halting operations at several fields, some of which are operated by the United States, according to Kurdish authorities.