The Indo-Pacific has emerged as the epicenter of global strategic competition. Home to over half the world’s population, nearly two-thirds of global gross domestic product (GDP), and some of the busiest maritime trade routes, the region is central to global security and prosperity. It is also China’s backyard, and Beijing’s growing geopolitical and economic footprint has triggered a flurry of Indo-Pacific strategies from the West.

Despite these stakes, the Trump administration has yet to articulate a defined strategy for US engagement. So far, its two most notable moves in the region have been gutting the US Agency for International Development (USAID) and imposing some of the highest tariff rates announced on “liberation day.” These measures risk severely damaging this region’s economies and eroding goodwill.

Compounding this, Defense Secretary Pete Hegseth recently urged Indo-Pacific countries to increase their defense spending to 5 percent of their GDP. Even the region’s largest defense spenders would need to more than double their current budgets to meet that target. This would divert scarce resources away from sectors vital to long-term stability and growth—sectors already strained by the loss of critical US development support.

Security is rightly a priority for the United States in the Indo-Pacific. But in a region with a substantial development and infrastructure gap, scaling back on economic engagement while urging countries to boost defense spending risks alienating key partners. This imbalance creates an opening for China, which is both willing and well-equipped to step in with development financing and infrastructure investment. Without a more balanced strategy that pairs security alliances with meaningful economic and diplomatic engagement, the United States risks ceding long-term strategic influence in the region.

Development cuts are a strategic misstep

USAID had long served as a cornerstone of US influence in the Indo-Pacific. With operations in more than thirty countries in the region and more than one hundred small and large-scale projects across the Pacific Islands, USAID played an integral role in advancing a free and open Indo-Pacific. This was crucial because of the region’s strategic importance and because the Indo-Pacific faces mounting challenges. From accelerating climate change to increasing security threats from China and North Korea, the region is a complex and volatile environment. Compounding this volatility is a significant gap between its infrastructure needs and government investment—one of the largest globally—which continues to obstruct economic progress and regional connectivity. USAID helped tackle infrastructure bottlenecks, advanced climate resilience, promoted governance and public health, and provided critical stabilization in fragile environments.

With US foreign aid on pause pursuant to US President Donald Trump’s executive order “Reevaluating and Realigning United States Foreign Aid,”* those vital development ties have been severed. There are limited alternatives to fill these gaps—leaving a vacuum that China is already stepping into with targeted aid and infrastructure investments that advance its interests while building long-term economic dependencies on Beijing.

China’s development diplomacy

There is a tendency in Washington to overestimate its capacity for coalition building while underestimating that of China. In 2021, then US Secretary of State Antony Blinken said that China lacks what he called the United States’ unique asset—“the alliance, the cooperation among like-minded countries.” Multilateral initiatives such as the Quadrilateral Security Dialogue and the Australia–United Kingdom–United States partnership known as AUKUS, as well as numerous bilateral alliances, have been spotlighted as great successes of US coalition building in the Indo-Pacific. However, China has long understood that influence doesn’t always require formal alliances. Through its Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), it has built a vast web of strategic infrastructure—from the China-Laos Railway to ports in Pakistan and Myanmar—that serve both local development needs and Beijing’s long-term geoeconomic ambitions, such as reducing reliance on strategic chokepoints.

Though often criticized for creating asymmetric dependencies, BRI projects fill real gaps that Western alternatives have neglected. However, economic alignment also often comes with political expectations—most notably, adherence to the “one China” policy. Pakistan, Cambodia, and Myanmar have offered strong diplomatic support for China’s positions on Xinjiang and the South China Sea in return for economic backing. Cambodia, for example, has blocked criticisms of China’s maritime claims from the Association of Southeast Asian Nations.

These asymmetrical dependencies have prompted some pushback. In 2017, Nepal canceled the Budhi Gandaki Hydropower Project with China over transparency issues, and in 2019 Malaysia renegotiated the East Coast Rail Link for better local terms. At the same time, countries across the Indo-Pacific have shown a growing interest in partnering with the United States on economic and infrastructure initiatives where possible. The recent US-Philippines partnership to co-fund a major railway under the Luzon Economic Corridor signals what’s possible when Washington actively engages. A Filipino spokesperson claimed that through this project the Philippines had “sent a strong message that in today’s geopolitical landscape, military and economic support for key allies must go hand in hand.” This signals a crucial reality: As infrastructure and investment gaps persist across the region, many countries may find it difficult to reject Chinese funding outright—particularly if viable alternatives remain limited.

US retreat, Chinese advance

China is moving quickly to fill the gaps created by the United States’ retreat from foreign aid. Within a week of the United States canceling child literacy and nutrition programs in Cambodia, China announced nearly identical initiatives. Prior to its foreign aid retreat, the United States had also funded 30 percent of the demining operations in Cambodia, focused on removing landmines left behind in the Vietnam War. Cambodia’s leading demining authority has since announced that China will provide $4.4 million to support these projects—an effort that was once considered a key link between the United States and Cambodia.

Myanmar is another example. In the aftermath of a major earthquake in March, rescue teams from across the world—including China and Russia—rushed to support the region. The United States was noticeably absent from these efforts, only surfacing days later when it deployed a small USAID emergency team and pledged two million dollars in aid—a small sum compared to China’s promised fourteen-million-dollar aid package. Natural disasters are a frequent and economically devastating reality in the Indo-Pacific, and the United States has historically played a leading role in relief and recovery efforts. Now, however, that space is increasingly being filled by China.

In the Pacific Islands—the world’s most aid-dependent region—China has launched new development partnerships in the absence of US assistance. Beijing announced plans to bolster support for the region’s climate change efforts, committing to one hundred small-scale projects over the next three years. It has also pledged two million dollars in investments focused on clean energy, fisheries, ocean conservation, low-carbon infrastructure, and tourism. Beyond multilateral initiatives, China is also seeking to strengthen bilateral ties through agreements such as its recent deal with the Cook Islands.

China’s efforts extend beyond expanding development aid. Seeking to deepen ties with Southeast Asian countries shaken by Trump’s trade war, Chinese President Xi Jinping launched a diplomatic charm offensive in April, traveling to Vietnam, Cambodia, and Malaysia to promote China as a “stable partner” in light of global economic disruptions. Ultimately, the suspension of US foreign assistance has handed China an opportunity to expand its soft power in the Indo-Pacific at the expense of the United States.

What can the US do?

The Indo-Pacific doesn’t just want military alliances—it wants railways, schools, and hospitals. It wants partners who show up with solutions, not just rhetoric. In that context, the US withdrawal from economic aid sends the wrong message at the worst time.

To maintain strategic influence in the Indo-Pacific, the United States must rebalance its approach. While Trump is intent on reducing foreign aid and has shown no signs of bringing back USAID to its previous size, US policymakers have plenty of options to reengage with Indo-Pacific countries on their development goals and prevent China from gaining more of a strategic foothold in the region.

- Trump should visit the Indo-Pacific. A presidential visit would reinforce bilateral alliances, demonstrate US commitment to the region, and open new avenues for advancing positive economic statecraft in support of US interests.

- Congress should expand the US International Development Finance Corporation’s (DFC’s) mandate, scale, and capabilities. With the rollback of USAID, the DFC—which is up for reauthorization this year—has become the United States’ primary instrument of affirmative economic statecraft. It therefore serves as the most effective counter to China’s BRI, offering a transparent and sustainable alternative to Beijing’s development financing across the Indo-Pacific. Strengthening the DFC will enhance the United States’ ability to compete economically and strategically in the region.

- The US government should prioritize de-risking private sector investment in Indo-Pacific markets. To compete with China’s development financing model, the United States should expand access to political risk insurance through agencies such as the World Bank’s Multilateral Investment Guarantee Agency and the DFC.

- The Trump administration should adopt an economic strategy in the Indo-Pacific that furthers US strategic goals in the region. This strategy should be focused on strengthening supply chain resilience, enabling mutually beneficial economic growth and development with Indo-Pacific partners, and ensuring that the United States maintains strategic influence in the region.

The United States’ withdrawal of foreign aid threatens to undermine its economic, diplomatic, and strategic influence in the Indo-Pacific, creating space for China to expand its foothold. The Trump administration and Congress must act now to reinvest in its economic partnerships in this critical region.

Lize de Kruijf is a program assistant with the Atlantic Council’s Economic Statecraft Initiative.

Nazima Tursun is a former young global professional with the Atlantic Council’s Economic Statecraft Initiative.

Note: Some Atlantic Council work funded by the US government has been suspended or terminated as a result of the Trump administration’s Stop Work Orders issued under the Executive Order “Reevaluating and Realigning US Foreign Aid.”

Further reading

Tue, Jun 24, 2025

The ‘ironclad’ US-South Korea alliance is outdated. A new age requires a ‘titanium’ alliance.

New Atlanticist By Markus Garlauskas

Washington and Seoul must set a new foundation for the seventy-year-old alliance that reflects the current strategic environment.

Thu, May 15, 2025

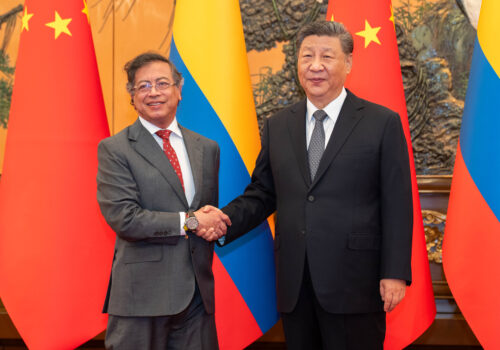

Four questions (and expert answers) about the China-Latin America summit

New Atlanticist By

At the summit, China offered billions of dollars’ worth of credit and Colombia entered into the Belt and Road Initiative.

Mon, Feb 24, 2025

Trump’s dismantling of USAID offers a new beginning for Africa

AfricaSource By Rama Yade

African leaders should take advantage of the dismantling of USAID to propose new partnerships made up of direct investment and fairer trade, Rama Yade writes.

Image: A road named "Xi Jinping Boulevard" opens in Phnom Penh on July 19, 2024, after the country's latest infrastructure project completed with assistance from China, its major donor. Kyodo via Reuters Connect.