With interim president, Adly Mansour’s constitutional declaration on July 7, a new system was adopted to amend the currently suspended Egyptian constitution, with two committees formed to carry out the task. The first committee of ‘ten experts,’ has completed its work, while the second, the ‘Committee of Fifty’ will begin its work on September 8.

The ten-man expert committee—made up of six judges and four constitutional law professors—worked for a period of one month, finishing their work on August 18. The committee came under severe criticism because of the secrecy and lack of transparency surrounding its work. No details were officially published regarding the committee’s work, or on its discussion or voting process.

The constitutional process will be impacted negatively due to the fact that the ten-person committee does not have the right to vote on the final draft of constitutional amendments. The committee is permitted to attend the Committee of Fifty meetings, but simply in the capacity of participating in the discussion. The draft amendments approved by the ten-man committee are in no way binding on the Committee of Fifty, so this reflects a significant loophole with the representation of judges and constitutional law professors, the two most important groups which should be involved in the constitution-writing process. Essentially, all of the work done by the ten-man committee could be changed or abandoned. It is worth mentioning that once the Committee of Fifty has completed its work, the ten-expert committee (together with a select few from the fifty), will be left only with the ‘technical’ task of finalizing the draft, because of their expertise. An appropriate solution to this problem is the ten-man committee joining the Committee of Fifty, in a more active capacity. This way, the legal experts’ voices would be included in a final vote.

The Amendments

The ten-man committee undertook wide-scale amendments to the 2012 constitution. Of the 236 original articles, they removed thirty-eight articles, leaving the draft with only 198 articles. Seventy-four of these articles were carried over from the 2012 constitution with no amendments. The remaining 124 articles were amended either entirely or partially.

In their amendments, the ten-man committee tended towards conciseness in several of the constitution’s articles, as well as opting for brevity in the wording of the constitutional text. This is a positive change, both constitutionally and linguistically. It is known that the more that constitutional texts tend towards conciseness and brevity, the more that constitution will be able to cope with an ever-changing reality and provide solutions to the diverse problems facing the society at different stages of its development.

The 2012 constitution underwent significant changes with more than two thirds of the articles changed, either by deletion, addition, or amendment. There is no doubt that after all of these amendments, we are now looking at the draft of a new constitution. This could cause widespread debate in the future, particularly amongst Islamists, regarding the level of commitment to the constitutional declaration which stipulated the undertaking of “constitutional amendments” and not a complete change of the constitution.

The Committee of Fifty

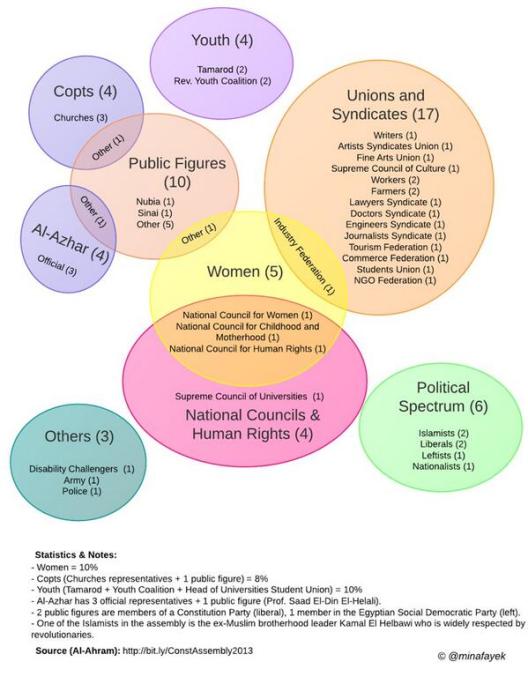

Two weeks ago, the criteria for choosing members of the Committee of Fifty was announced, along with the percentage allocated to each party or institution. On Monday the members were revealed, and of the fifty, two Islamists, five women, and four Copts were chosen.

More importantly, only six out of the fifty seats are allocated to political parties. The six seats are divided among two Islamist members, two liberal members, one nationalist member, and one leftist member. This distribution is the most conspicuous problem in the make-up of the Committee of Fifty, because it does not take into account the actual size of the Islamist current with its different factions—the Muslim Brotherhood, Salafi parties, the Wasat Party, and al-Jama’a al-Islamiya’s Construction and Development Party. This Islamist faction is in no way less than fifty percent of Egyptian society, regardless of the recent political events over the past two months. If we want to depend on a correct apportionment of the political trends during the past two years, there were no more than two major camps: Islamists and, on the other side, all those who can be identified as the ‘civil’ trend. The civil side includes liberals, nationalists, and leftists. Consequently, the allotment of the political parties’ seats in the Committee of Fifty should have been split equally between the two main camps in Egypt, giving Islamists three seats and civil parties the other three.

An extremely important consequence of this unfair Islamist representation in the Committee of Fifty is a deepening feeling of exclusion and isolation among Islamists. Most Islamist parties, with the exception of the Nour Party, rejected participating in the events following Morsi’s removal on July 3, including the amendment of the constitution.

Of the two Islamist representatives, one belongs to the Salafi Nour Party. Bassam Zarqa, the party’s vice president, will participate in the committee after the party seriously considered withdrawing. The Nour Party, the largest representative of the Salafi movement in Egypt, announced its extreme dissatisfaction with both the make-up and selection process of the Committee of Fifty. Despite its clear prejudice against the representation of the Islamist trend in general, the party finally decided that a lack of participation would only serve to be more detrimental to the process.

Dr. Kamal al-Hilbawy, the other representative chosen to represent Islamist parties, is an independent Islamist personality who does not actually belong to a party. In addition to unfair representation of Islamists in the Committee of Fifty, the committee does not include a representative from the Islamist parties that opposed Morsi’s removal: the Muslim Brotherhood, the Wasat Party, and the Construction and Development Party. This shows the continued failure of all political factions in Egypt, including the Muslim Brotherhood, to use political negotiation to compromise and resolve Egypt’s successive crises over the past two years. There is no doubt that this will be reflected in the work of the Committee of Fifty and in the constitutional amendments that it will produce. Islamists will continue to reject the committee and its work, resulting in a continuation of the political crisis in Egypt and the detraction of the “legitimacy” of the new constitution’s drafting. The crisis in Egypt, however, cannot withstand further escalations or isolation. Instead, it is in need of an inclusive process for all, whether Islamists or otherwise, as long as they were not involved in violence, or the incitement of violence.

Yussef Auf is a fellow with the Rafik Hariri Center for the Middle East. His work focuses on Egyptian constitutional issues, elections, and judicial matters. He has been a judge in Egypt since 2007.

Chart created by Mina Fayek.