Within days, Egyptians are going to vote in a public referendum on an amended proposed constitution, the nation’s second in two years. The proposed document includes a number of significant improvements as compared to the now-suspended 2012 constitution.

Within days, Egyptians are going to vote in a public referendum on an amended proposed constitution, the nation’s second in two years. The proposed document includes a number of significant improvements as compared to the now-suspended 2012 constitution.

Many observers have identified the flaws of the proposed amendments and, indeed, the document offers a number of disappointments. Among its shortfalls, the document maintains the jurisdiction of military courts to try civilians under certain conditions, limits the freedom of worship to only the three (“heavenly”) Abrahamic religions, continues to insulate the military establishment from civilian (or any) oversight, appeases several state institutions by providing them with undue constitutional guarantees, and lacks vision for genuine reform in state structures. These are only but a few of the problems presented in this proposed constitution – and they are not insignificant.

Having said that, it is equally important to recognize some of the major developments in this document, particularly, in the chapter on rights and freedoms. If adopted, the proposed constitution will provide the human rights community with useful tools that, under the right conditions, could potentially be used to challenge the status quo and any future legislation that attempts to chip away at people’s rights. The constitution alone, however, will not improve the human rights situation in Egypt. The political context in which this Constitution is applied will play a more important factor in protecting these rights than an isolated reading of the text without regard to the surrounding environment.

Without ignoring or underplaying problems that exist within the current draft, it is worth highlighting some of the overlooked changes that represent positive progress:

Guaranteeing gender equality: Last year, the Islamist-dominated constituent assembly refused to guarantee gender equality in the constitution, limiting it in accordance with the provisions of Sharia. After contentious debates, they removed it entirely from the provisions of the 2012 constitution, instead, making only a general and passing reference to equality in the preamble. The 2013 proposed constitution (Article 11) obligates the state to “guarantee the achievement of equality between women and men in all civil, political, economic, social and cultural rights.” It also provides protection to women from “any form of violence.”

Banning torture: Article 52 of the Proposed Constitution bans all forms of torture (not just during detention). This new article also exempts the crime of committing torture from any statute of limitation. This could, in theory, create better mechanisms for seeking justice for victims of police abuse in the future, even if such mechanisms are not available at the time of the crime.

Better antidiscrimination provisions: Article 53 establishes a considerably stronger antidiscrimination framework. First, the article provides a wide range of bases upon which discrimination is prohibited, including, for the first time, “disability, social class, political or geographic allegiances, or any other reason.” Second, to further combat discrimination, the article makes hate speech a crime punishable by law – a progressive move relative to other democratic states (although the article could also potentially be abused to restrict legitimate free speech). Third, the article requires the state to eliminate all forms of discrimination and to create an independent commission to undertake this role.

Stronger protections for the rights of the child: The proposed constitution provides stronger protections for the rights of children. Consistent with international standards, article 80 explicitly defines anyone under the age of 18 as a child. This was a prominent demand made by the human rights community during last year’s constitutional debates but the constituent assembly refused to recognize it in the 2012 constitution. The Islamist-dominated assembly at the time argued that Sharia does not recognize a specific childhood age. Not only does article 80 expand the scope of protection to all children, but it also provides additional protections, including prohibiting child labor in any sector that could expose the child to danger; protecting the child from all forms of physical, commercial, and sexual abuse; creating special courts for juveniles; and mandating that all child-related legal procedures must be taken according to what is in “the best interest of the child.” The article also guarantees the right to early childhood education.

$1§ Stronger protections for the rights of the elderly and persons with disabilities: Articles 81 and 83 of the proposed constitution require the state to ensure that the rights of persons with disabilities and the elderly are protected, such that they have equal opportunities to integrate into all aspects of society.

Explicit ban on human trafficking: The 2012 constituent assembly refused to impose an explicit ban on human trafficking, preferring instead to prohibit sex trade and other forms of “exploitation.” Some members argued at the time that a ban on trafficking would also ban underage marriage, which they believed was contrary to Islamic sharia which, according to them, allows marriage as early as the age of puberty, no matter when that might be. The proposed constitution amended this by adding article 89 an explicit ban on human trafficking and all forms of slavery.

Rights and freedoms supersede legislation: Article 92 prevents the legislator from passing any laws that would limit any rights or freedoms in a way that would “impinge on their essence or the origin.” This language existed in the 2012 constitution (Article 81) as well but it was also followed by a clause that subjugated the entire chapter on rights and freedoms to the limitations of the chapter on “the basic components of the state.” This included potentially strict interpretations of Sharia, an obligation to protect the “authentic nature of the Egyptian family,” and an expansive role for an unelected and unaccountable religious institution – Al-Azhar. The 2013 amendment, which does not include this “basic components of the state” qualifier, provides a useful tool to challenge the constitutionality of any legislation that attempts to strip these rights away by an overzealous legislature. The recently enacted protest law, which raised much controversy due to its oppressive limitations on freedom of assembly, is a likely candidate to be challenged in court pursuant to the mechanism provided by this tool.

Binding Egypt to international human rights conventions: Another potentially useful tool appears in article 93, which commits Egypt to comply with any human rights treaties and conventions that the country has ratified. More importantly, the article gives such international instruments the power of law within Egypt. As a result, enforcing such treaties in Egypt will not simply depend on the political will of the government but also pursuant to a legal obligation. This could provide considerable support to Egyptian human rights activists in their persistent struggle to bring Egypt’s laws closer to the international standards.

A more balanced role for religion: Unlike what many Islamists feared, this proposed constitution does not create a secular state. Nevertheless, it brings Egypt back to its decades-old equilibrium (and tensions) between the role of religion in government versus that of civic institutions. To the dismay of many secularists, Islamic sharia remains the primary source of legislation but it is up to the courts to decide when a law has veered from the principal tenets of Islam, as opposed to Al-Azhar, as was the case in the 2012 constitution. More importantly, the current draft repeals the controversial article 219, which allowed for extreme interpretations of sharia to potentially serve as the basis for legislation. In addition, article 7 of the current draft strips Al-Azhar of the legislative role it had in the 2012 constitution – an advisory but authoritative role that would have elevated the power of the religious institution to an unprecedented level in Egypt.

These proposed amendments represent a welcome departure from the Egyptian constitutional legacy in these areas of rights and freedoms. These provisions, however, will be useful tools for human rights advocates only if there is political will to enforce them. Among other factors, the extent to which these articles will be enforced will depend largely on the willingness of the Supreme Constitutional Court to assert its independence and not shy away from a stand-off with future governments and their legislatures.

Nonetheless, working with a good text is far better than the alternative. The Egyptian experience since January 25 has demonstrated that Egypt will not realize its democratic aspirations overnight (or over three years). Improving Egypt’s political reality requires a lengthy series of small steps. Despite its flaws, the progress made in this Proposed Constitution is one such step forward.

Tamer Nagy Mahmoud is an Egyptian attorney at an international law firm in Washington, DC. He has advised members of the 2013 Committee of Fifty, the 2012 Constituent Assembly, political parties, and civil society, on matters of constitutional reform. He is a member of the Public International Law & Policy Group (PILPG) a founding member of the Egyptian Independent Association for Legal Support (Sheraa), and a member of the Egyptian-American Rule of Law Association. The views presented in this article are his own.

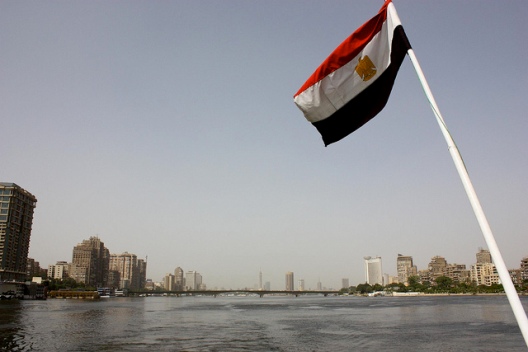

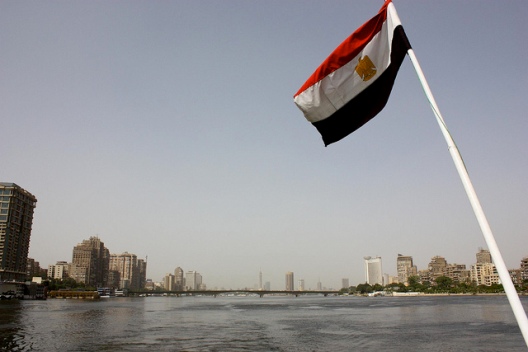

Image: Photo: Johanna Loock