By killing Mahsa Amini, the Islamic Republic has created millions of Medeas

In Greek mythology, when the hero Jason betrays his wife, the princess Medea of Colchis, and marries another woman, Medea exacts the most horrible revenge and kills her rival and even her own children. In today’s Iran, millions of latter-day Medeas are bravely telling the world they have had enough of mistreatment by a brutal regime.

It is possible that the mythological Medea was originally Iranian. Colchis, in today’s Western Georgia, is a region that was long under Iran’s cultural, as well as political, influence. Herodotus, in The Histories, adds the detail that Medea and her son Medeus ended up on the Iranian plateau, and that the inhabitants took their name “Mede” from her and her son. He writes, “Long ago the Medes had been called Arians by everyone, until Medeia of Colchis came to them from Athens, and then, at least according to what the Medes themselves say, they, too, changed their name.”

It’s no surprise that the clerical elite that rules the Islamic Republic has been as obtuse as Jason. Through its blindness, it has brought catastrophe on itself. Its brutal and misguided actions have provoked the anger of millions of Iranian Medeas, who are seeking revenge, first for their murdered 22-year-old sister Mahsa Jina Amini, the young Kurdish woman fatally beaten in the custody of the so-called “morality” police, and second, for decades of mistreatment and discrimination by the Islamic Republic. Their search for revenge could destroy the entire fragile structure of the state.

Iran has changed a great deal since the early days of the Iranian revolution in the 1980s, but its leadership has not. A tight-knit fraternity of powerful clerics—Mohammad Beheshti, Ali Akbar Hashemi Rafsanjani, Ahmad Jannati, Mohammad Reza Mahdavi Kani, Mohammad Yazdi, Ali Khamenei and others loyal to the visions of Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini—seized power in bloody clashes that followed the collapse of the monarchy and crushed opposing Marxists, socialists, moderates, and traditional clerics. For four decades, presidents, ministers, and parliaments have come and gone, but this group of revolutionaries and its acolytes—despite the death of many of its members—has remained firmly in control of the levers of power.

While some of the personnel have changed, the philosophy of the ruling elite has not, despite the enormous changes in the larger society. The elite remains committed to the attitudes of the 1980s, when Iran was at war with Iraq and much of the rest of the world, and Khomeini’s word was law. In those violent years, the morality patrols—staffed by those loaded with grievances and resentments—ran amok, harassing anyone whose appearance, dress, speech, or music, did not conform to the most rigid view of what those in power considered proper and Islamic. Questioning the prevailing madness was equivalent to treason. There were no doubts, no debates. Iranians went along or were crushed.

For Iran’s women, who had been at the forefront of the broad uprising that brought down the monarchy in 1979, the message of the triumphant revolution was: Ya rusari, ya tusari (Cover your head or we will smash it). Throughout 1979, demonstrations against measures to limit women’s rights and to make veiling compulsory were attacked by thugs with clubs, knives, chains, and even acid.

While the ruling elite enjoyed its power and privileges, it failed to notice that Iranian society was changing. Iran’s population is now 86 million, more than double what it was in 1979. Less than 20 percent of the population has any memory of pre-revolutionary Iran. Literacy rose from about 50 percent to well over 90 percent. Girls whose conservative parents had kept them out of middle school and high schools were now, shielded by dress codes, flooding both secondary schools and universities. Universities appeared in places like Kashan, Sanandaj, and Yazd, where higher education had formerly required leaving one’s family for the big cities. Provincials who earned advanced degrees could become professors in their hometowns they had previously fled because of lack of opportunity.

Along with this population growth, came the emergence of a population that is smart, creative, well-educated, curious about the world, and enormously tech-savvy. Iranian women—holding about sixty percent of university places—are at the forefront of this new and dynamic society, which stands in clear opposition to the rigid ideas of those who rule the Islamic Republic.

By the end of the second decade of the new century, the clerical establishment did not like what it was seeing. It saw new art and music it did not understand. It saw young people ridiculing and ignoring its rules. It saw the morality police lose their former power to intimidate (though they continued to arrest women, sometimes violently). These rigid and isolated clerics at the top unwisely thought they could stop change by re-imposing the outdated rules of 43 years ago.

In July, President Ebrahim Raisi announced a “hijab and chastity” law and sent more morality police—still loaded with its class resentments—in a fruitless attempt to re-create their glory days of unquestioned authority. The result was inevitable: confrontations between a savvy and progressive society, and a calcified and brutal state.

These confrontations became tragedy on September 16, after the murder of Amini. Following her death, Iranian women and girls have decided they had had enough of mistreatment. Going beyond a demand to make hijab a matter of choice, they would take to the streets and vocalize their discontent for decades of humiliation, degradation, brutality, and the tyranny of senseless rules. Removing their hijab and in some instances burning it, they also stomped on the ubiquitous images of the Supreme Leader and founder of the Islamic Republic—or gave them the finger—demonstrating that these women and girls would no longer put up with a clerical establishment.

It has been said that most governments are only two bad decisions away from collapse. In some cases, it is only one decision. Washington’s decision to insist on judicial immunity for American military advisers in Iran in 1963 made Ayatollah Khomeini— previously an obscure, right-wing scholar preaching against coeducation—into an Iranian national hero who would lead the broad coalition that brought down the Shah. Fourteen years later, Mohammad Reza Shah’s decision to order the publication of an anti-Khomeini editorial in January 1978, which started the avalanche that in only one year destroyed the Iranian monarchy.

The besieged elite’s decision to restore at least the appearance of the society of the repressive 1980s and to allow its “base” in the morality police to enforce the obstinate triviality of pointless rules, is clearly a similar bad decision with equally disastrous consequences.

The legendary Medea had no intention of accepting her betrayal and forgiving Jason and the other men of Corinth who had mistreated her. Nursing her grievances, she would exact the most appalling vengeance. Today, Iran’s oblivious aging rulers have, like Jason, gone too far. Now they must face a million Medeas with no thought of forgiving and determined to have their revenge.

John Limbert is a retired professor of Middle Eastern Studies at the United States Naval Academy in Maryland. A Foreign Service Officer for thirty-four years, he served as deputy secretary of state for Iran under the Obama administration. He was among the fifty-two Americans held hostage during the 444-day Iran hostage crisis. He is the author of Iran: At War with History, Negotiating with Iran: Wrestling the Ghosts of History, and Shiraz in the Age of Hafez.

Further reading

Wed, Sep 28, 2022

I’m a member of Gen Z from Tehran. World, please be the voice of the people of Iran.

IranSource By

To all the brave and beautiful people out there who know what freedom feels like, be our voice.

Mon, Sep 26, 2022

‘Women, life, liberty’: Iran’s future is female

IranSource By

Women, young and old, have been at the forefront of the uprising, just like every other protest in Iran over the past decades.

Fri, Sep 30, 2022

The protests in Iran have an anthem. It’s a love letter to Iran.

IranSource By

Shervin Hajipour's “For the sake of” has captivated the whole nation.

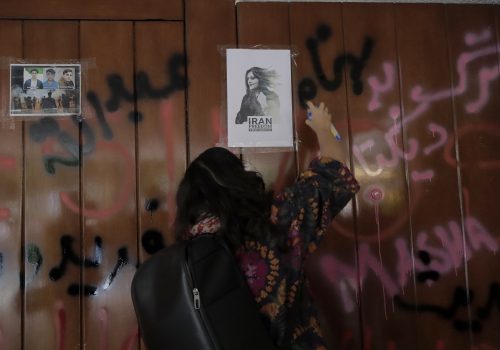

Image: Hairs cut by women near a drawing depicting Mahsa Amini. A protest march took place in Toulouse in solidarity with women in Iran, following the death of the young Iranian woman, Mahsa Amini, who died after being arrested by the Islamic republic's 'morality police'. Police have said Amini fell ill as she waited with other women held by the morality police, who enforce strict rules in the Islamic republic requiring women to cover their hair and wear loose-fitting clothes in public. The death of Mahsa Amini sparked protests worldwide. Several hundreds of people participated to the protest. Toulouse. France. October 9th 2022. (Photo by Alain Pitton/NurPhoto)