Iranians are knocking clerics’ turbans off. This isn’t an anti-religion act but an indirect tool for accountability.

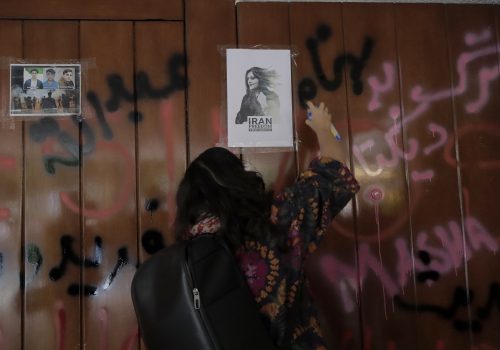

The September murder of Mahsa Jina Amini by the so-called morality police was the spark that has now fueled a revolution in Iran. The door has been opened to unprecedented, yet effective, movements for human rights and justice, including anti-government chants, burning and removing mandatory hijab, vandalizing regime apologists’ cars with “Death to [Supreme Leader Ayatollah Ali] Khamenei,” spray painting the names of protesters killed by security forces on walls, and, most recently, knocking turbans off of clerics’ heads.

This viral trend of #Turban_Throwing (#عمامه_پرانی) is not an attack against Islam as a religion and faith, but rather a stand against a regime that has used religious practices as a cover to commit unimaginable violence.

Since the nationwide anti-government protests began on September 16, not many clerics roam the streets in towns and cities in their aba and ghabeh (clerical robe attire) and black or white ammameh (turban). Those who dare risk meeting an Iranian civilian, usually under the age of twenty-five, who knocks their turban off and runs away.

This newest trend took off on October 22, when a video circulated on Persian language social media of a young man walking up to a cleric, knocking his turban off, and sprinting away, while the cleric bends over to try and collect himself. This first instance occurred in the holy city of Qom, one of the most powerful strongholds for Shia clerical institutions. Since then, countless other videos have been posted online and shared from across the country.

The situation has become so dire for clerics that they are now experimenting with different methods of keeping their turbans in place or even carrying spares, just in case. One viral meme even jokingly suggested a turban helmet, while another encouraged protesters to steal the turban so its meters-long fabric can be used as a fuse for numerous Molotov cocktails.

The spirit of the revolution can be felt in these videos—led by Gen Z who are at the forefront of the uprising. These youth are treating the clerical establishment with the same teenage antics they use on their parents and teachers. It’s this fearless and defiant generation, who are connected to each other through a highly-censored Internet and social media, that are only capable of flabbergasting a well-established dictatorship that has devastated Iran since 1979.

Turban toppling is not anti-religion

The turban is one of the three parts of Shia clerics’ dress that supplements their clerical attire. People who argue that this dress was worn by clerics for centuries and should be respected as part of the right to freedom of religion or that this viral trend is anti-religion must be reminded of the fundamental shift in the meaning and function of that very dress worn by the Islamic Republic’s clerics.

The truth is Iranians have felt anger and resentment towards clerics for some time. For years, citizens have walked by and spit on them in the streets and taxi drivers have even denied them rides—a problem so well known that it was even captured in the 2004 Iranian film, Marmoulak (“The Lizard”). However, not until the current protests have acts against the clerics become so bold and popular, gaining momentum and meaning amid this revolution.

Within the Islamic Republic framework, clerical garbs have become a tool to hide behind while also serving as a reminder of the trauma inflicted on its naysayers. This attire has been used for four decades as a uniform of the regime—worn to justify wreaking unspeakable sufferings, supposedly in the name of God, including the harassment of women by clerics, as evident by a viral video compilation in the wake of these ongoing protests.

The Constitution of the Islamic Republic of Iran establishes a Shia theocracy by placing the Shia school of Islam above all other religions and appointing Shia clergies as the ruling class. In essence, high-ranking clerics must review all governing matters according to Islamic criteria, making the Supreme Leader a ruler above the judiciary, government, and parliament. Article 177 iterates that the articles of the Constitution that construct the Islamic character of the political system are unalterable. Thus, the path was opened for a ruthless dictatorship, which is the precise situation Iranians have faced for over four decades.

The clerical garb worn in Iran has been associated with repression and numerous atrocities. Some of these atrocities, such as the 1988 massacre of political prisoners, which resulted in the mass executions of 4,500 to five thousand people, or the November 2019 crackdown on protests, in which security forces arrested and killed thousands, amount to crimes against humanity and war crimes. The ruling class is also responsible for vast corruption, nepotism, and mismanagement that have drained Iran’s resources and wealth. It’s no surprise why ordinary Iranian citizens are engaged in this symbolic revolutionary act.

The act of turban toppling, as well as burning the headscarves, are a manifestation of anger and frustration; protestors are disempowering the patriarchy and the tyranny turbans represent for Iranians.

Time to take a stance

The non-violent act of knocking clerics’ turbans off is a sign of the first real cracks appearing in the Islamic Republic. For once, the regime and its pawns are the ones humiliated. What used to incite fear no longer has any power. If identified, these protestors are at risk of arrest and torture, and may face harsh sentences for insulting the sacred. However, by risking their lives to create this trend, they have generated an indirect tool for accountability.

Above all, the importance of this specific act has manifested in calls on social media for clerics who have not been involved in human rights abuses or corruption to distance themselves from the regime. Even those very few clerics who have not had any association with the government cannot deny that the mere act of being a Shia cleric in dress has given them a privilege ordinary Iranians do not share. There are suggestions on social media that clerics should put aside their turbans and robes—or even burn them as symbols of crime and corruption—in support of the uprising.

This is the beginning of a difficult but necessary discussion for the transitional justice process: how should Iranians deal with the Shia clerical establishment once the regime is overdrawn? Would Shia religious schools be closed and their symbols—in particular, their dress—be banned or only limited to religious places such as mosques?

Whatever the answer, young Iranian protestors are already challenging the morals of those who continue to wear the regime’s uniform. The clergies who have not participated in atrocities or corruption must take the side of the people and have a say in Iran’s future, or wait for their fates to be decided by a country that sees them as the oppressive class.

Shadi Sadr is a human rights lawyer and a member of the panel of judges at the International People’s Tribunals on Indonesia, Myanmar, and China. She co-founded and directed Justice for Iran, one of the organizers of the Iran Atrocities’ (Aban) Tribunal. Follow her on Twitter: @shadisadr.

Further reading

Wed, Sep 28, 2022

I’m a member of Gen Z from Tehran. World, please be the voice of the people of Iran.

IranSource By

To all the brave and beautiful people out there who know what freedom feels like, be our voice.

Wed, Jan 26, 2022

Aban will not die: How truth remains a powerful weapon against the Islamic Republic

IranSource By

In November 2021, The Iran Atrocities (Aban) Tribunal in London investigated if Iranian government officials, police, and military forces had committed crimes against humanity during the November 2019 protests. In front of the eyes of the Iranian public, bit by bit, pieces of the truth were put together.

Mon, Sep 26, 2022

‘Women, life, liberty’: Iran’s future is female

IranSource By

Women, young and old, have been at the forefront of the uprising, just like every other protest in Iran over the past decades.

Image: Two Iranian clerics talk to each other while attending a religious conference in Qom, 120 km (75 miles) south of Tehran, March 10, 2011. The clerics are attending the International Conference of Religious Doctrines and the Mind-Body Problem. REUTERS/Morteza Nikoubazl