The resignation of Iranian Foreign Minister Mohammad Javad Zarif came as a shock, and not just due to the delivery system. He made the announcement on an Instagram post addressed to his followers instead of official channels.

The timing was suspect as well. Zarif decided to leave office just as Syrian President Bashar al-Assad made a completely unexpected visit to Tehran which was quite unbeknownst to the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, according to sources in Tehran. To reporters who asked him about the news, Zarif responded, “After the pictures of today meetings, Javad Zarif has no more credibility in the world as the foreign minister.”

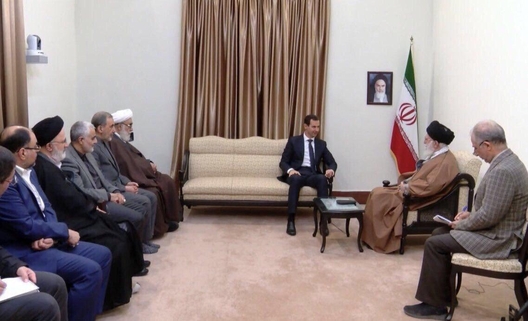

There were two sets of pictures both taken on February 25. The first set shows Assad’s meeting with President Hassan Rouhani and Qassem Soleimani, the commander of the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps’ Quds Force. The second set shows Assad meeting with Supreme Leader Ali Khamenei, along with his foreign policy advisor, Ali Akbar Velayati, head of the leader’s office Mohammad Mohammadi Golpayegani, Executive Deputy Vahid Haghanian—who has been described as Khamenei’s right hand—and Intelligence and Security Director, Asghar Mir Hejazi.

Following Zarif’s resignation, the pictures disappeared from both Khamenei and the president’s official websites. The removal of the pictures, especially on the Supreme Leader’s website, could indicate that Rouhani and Khamenei, in a coordinated move, were trying to control the damage and convince Zarif to stay.

Rouhani refused to accept Zarif’s resignation, saying it was contrary to the country’s interests. But according to the observers in Tehran it was Soleimani’s strong statements that brought the confusing situation to an end. “Mr. Zarif is in charge of the foreign policy of the Islamic Republic, and has always been supported by the top officials, especially the Supreme Leader,” he remarked on February 27. Soleimani added that evidence shows Zarif’s absence from the meeting was not intentional and merely caused by a lack of coordination in the administration.

Most likely Soleimani’s involvement was initiated by receiving a signal from Khamenei. The question is: if Zarif’s absence from Rouhani’s meeting with Assad was due to lack of coordination in the administration, which is hard to believe, then how can his absence from the Supreme Leader’s meeting with Assad be justified, especially considering that Velayati, Khamenei’s foreign policy advisor, was present at that meeting?

In any case, there are a few points worthy of note.

Zarif himself is part of the problem. By his own admission, he has little or no influence in policy matters and is, at best, a messenger. In an interview published on February 26 by the Islamic Republic newspaper, Zarif responded to allegations by hardliners thathe has not abided by the guidelines and orders of the Supreme Leader during key nuclear negotiations. Zarif countered that “For me personally, the most important criteria has been to abide by the Leader’s orders… During the [nuclear] negotiations most of my time was focused on the red lines that the supreme leader had drawn… Of course, this doesn’t mean that we could satisfy all the things that the Supreme Leader wanted… What we could not achieve we would report, would get a new instruction and would act accordingly.”

In other words, Zarif himself prioritizes obedience to the Supreme Leader over national interests. That hierarchy makes the kind of embarrassment that he faced almost inevitable. If Zarif or any other minister views an official’s mission as implementing the orders of the Supreme Leader, that person must accept being sidelined if that is what Khamenei wishes.

On another note, Khamenei has consistently used the moderates—such as Rouhani—and reformists—such as Mohammad Khatami—to escape the traps that he himself created for the country. Subsequently, he then would denounce compromise as sazeshkari, or surrender. This is exactly what happened with respect to the nuclear deal. Khamenei used Zarif and his negotiating team to conclude the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA) which lifted economic sanctions just as the country was about to explode due to skyrocketing prices. Then, a few months ago, he said, “The negotiations on the JCPOA were wrong. I was wrong to let the gentlemen, as a result of their insistence, try an experience. Of course, they crossed the red lines drawn [by me].” Iranian radicals received these statements with thunderous applause.

Khamenei has representatives in almost every Iranian institution, including ministries, universities, the armed forces, and so on. He appoints key figures in the armed forces and in the powerful Guardian Council, as well as the head of the judiciary. He also appoints all the Friday prayer imams in large and small cities. And last, but certainly not least, he appoints the head of the state radio and television, which propagates and promotes Khamenei’s worldviews and constantly attack the moderates (there is no private broadcast media network in Iran). These representatives and appointees come, without exception, from the most radical faction of the religious conservatives’ camp.

This domination of religious radicalism, led and imposed by Khamenei, has resulted in large scale urban middle-class disenchantment with, defiance of, and accumulated anger toward the system. This combination has effectively stripped the society of any meaningful stability, as evidenced by the continual chain of strikes and protests across the country. Given this existing tense climate, no stable and efficient economic macro-management system, practical long-term planning, or institutionalized system to fight economic hardships and prevalent corruption have had the chance to emerge. In the end, Khamenei and his hardliner allies routinely blame the moderate administration for all these shortcomings.

In terms of foreign policy, Khamenei’s imposed worldview is no less harmful to the economy than his domestic policies are. Shortly after the culmination of the nuclear accord between Iran and other key world powers, Khamenei banned any further negotiations with the US. As long as Iran continues its hostile position toward the US, does not move toward détente, and closes doors on any negotiations, the US will obviously react harshly. Even in the case of Obama administration, with its low-key approach and compromising spirit, it was a matter of time before President Barack Obama was forced to react to Iran’s anti-Americanism. Zarif is not so naïve as to ignore the fact that Iran will feel the massive brunt of US sanctions as long as Khamenei’s policy of “no-talks, no-détente” continues.

In Iran, it is widely believed that the Beyte’ Rahbari, or Supreme Leader’s office, is involved in the affairs of the country at the highest level. The presence of Mohammadi Golpayegani, the head of the Beyt since Khamenei assumed the post of leadership in 1989, Haghanian, Khamenei’s top aide, and Mir Hejazi confirms how much the leader trusts these three men. It is widely known that they hold powerful sway over Khamenei in most of his decisions.

One perplexing question is why Rouhani cast aside the foreign minister who had added so much to his political fortunes. When it comes to policies in Syria, Iraq, and Lebanon, Zarif is completely out of the loop. Even Rouhani does not play an effective role in that respect. Assad deals with Soleimani. In fact, it is safe to assume that Rouhani’s presence in the meeting with Assad was entirely due to diplomatic protocols.

Soleimani’s remarks regarding Zarif’s role in the Iranian foreign policy should be taken with a grain of salt. The Iranian late president Akbar Hashemi Rafsanjani once in an interview published in a biography said, “We now have a real problem [with theQuds Force]. The problem is that these forces have deprived the foreign ministry from conducting its responsibilities in the most sensitive countries. No one can appoint an ambassador in Iraq, Syria, Lebanon, Afghanistan, and Yemen without the approval of Quds Force.”

Shahir Shahidsaless is an Iranian-Canadian political analyst and freelance journalist. He is the co-author of Iran and the United States: An Insider’s View on the Failed Past and the Road to Peace. He is a contributor to several websites with focus on the Middle East as well as the Huffington Post. He also regularly writes for BBC Persian. Follow him on Twitter: @SShahidsaless.

Image: Bashar al-Assad in a meeting with the Supreme Leader and other high-ranking Iranian government officials (Jamaran.ir )