Atlantic Council president and CEO Fred Kempe interviewed General Colin Powell, former chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff and the 65th U.S. Secretary of State, on the end of the Cold War and the future security environment.

You were the chairman of the Joint Chiefs on the day that the Wall came tumbling down. What’s your take on what brought the Cold War’s end?

I credit the inadequacy, inefficiency and ultimately the failure of the Soviet Communist system of economics and governance. Beyond that, we executed a successful strategy of containment for all those years. It took a lot of people, over time to push the Soviet Union over the edge. We were blessed with wise leadership at a crucial moment. Ronald Reagan called the Soviets the “Evil Empire,” but he was secure enough in who he was and in America’s strength that he was willing to engage closely the leaders of that so-called Evil Empire.

You helped organize five summits between Gorbachev and Reagan. What was Reagan’s approach to Gorbachev?

Reagan’s greatest desire during that period was not to shove it in Gorbachev’s face or to shove it in the Russians’ face that they were failing, but to show them a better way. He was always saying, “Gosh, if I can only take Gorbachev out to California and show him the ranch. If only I could take Gorbachev to our auto plants in Detroit and show him what real industry looks like. If only I could show him our homes and our communities.” Reagan was so proud of America. He thought he could make a more powerful point with the Soviet leadership by showing them our accomplishments in comparison to their own.

Don’t forget that the Soviet Union and the U.S. were similar in their natural resources and population size. So it was the inadequacy of the system that was the Soviet Union’s undoing, and Gorbachev recognized that inadequacy. He thought, “I can fix this,” but he could not. I will always respect Gorbachev and consider him a friend and a major historic figure because he was there at the right time. But he had to be met by people like Reagan, Thatcher and Kohl.

How much credit should history give Reagan for ending the Cold War?

I give him a lot of credit. The Cold War’s end was coming anyway, but it would not have happened when and how it did if Reagan had not been there at that time to work with Gorbachev and to help Gorbachev as he did. We were trying to help him save the Soviet Union. We weren’t saying you have to give up the Soviet Union. We just said communism is a disaster.

That’s an important distinction.

I’ll never forget the last meeting that we had with Gorbachev at Governor’s Island in December 1988. It was after the election, so George H.W. Bush was the President-elect and he joined Reagan for the meeting. We weren’t looking for another summit with Gorbachev, but Gorbachev had come to speak to the United Nations and he wanted it.

Brent Scowcroft was there as the new National Security Advisor to replace me. It was mostly a chance for Gorbachev to say goodbye to Reagan and hello to President Bush. It was warm and friendly. The Russians had just announced the unilateral troop reduction at the U.N. an hour earlier, before Gorbachev got on a ferry to come over and see us. At one point President-elect Bush said to Gorbachev, “Well how do you think it’s all going to turn out?” And Gorbachev looked at him and said, “Not even Jesus Christ knows the answer to that.”

Reagan must have loved that.

He smiled. I could almost hear my boss saying, silently to himself, “I told you he was a Christian! I told you!” Gorbachev then told us that when he took over in 1985, everybody said, “Wonderful! We need a revolution and they were all applauding. And then two years later in 1987, when I started to do things with perestroika and glasnost and things got more difficult, the applause died down a bit. And now it’s 1989; the revolution is here and nobody is applauding. But still we’re going to have a revolution.” I found that very revealing, and I believed him.

You were one of the first to predict the Cold War’s end.

I went back to the Army and was commander of all deployed forces in the United States. I gave a speech in May 1989, several months before the Wall fell in November, to all of the senior Army generals. Everything they had done for the previous 40 years rested on there being a Soviet Union. I told them, “The bear looks benign,” and that we were “on our way to losing our best enemy.” I told them that if we opened NATO tomorrow to new members, we would have several new applicants on our agenda within a week – Poland, Hungary, Czechoslovakia, Yugoslavia, maybe Estonia, Latvia, Lithuanian, maybe even Ukraine.”

Was Gorbachev naïve in thinking he could reform the system?

I would never call him naïve. He really believed in the Soviet Union. He thinks one of the greatest disasters that ever befell the Russian people was the collapse of the Soviet Union. He really thought he could save it. But it became clear over time that it was not sustainable. It was rotten, notwithstanding what our intelligence agencies were telling us about its economic and military strength. They had a lot of guns but they were busted on butter. And in the 20th century, butter was as important as guns. Gorbachev had two goals: to preserve the Soviet Union and to end the Cold War because it was bankrupting them.

You were a young officer in Germany around the time that the Berlin Wall was built in a place called Gelnhausen. They’ve since named a street for you there. What were your impressions of the Cold War then?

I was just a 21-year-old second lieutenant out of New York, having just finished infantry school. We all knew our jobs. When the balloon went up, my job was to race to our positions at the Fulda Gap and beat the crap out of the Russians as they came through. That was it. We didn’t need to know much more. I still remember being taken up to the Fulda Gap and seeing it for the first time. It’s a huge, gorgeous valley. I still remember being shown where my position was between a couple of trees where we would stop the Russian Army. I had a mission to guard one of the 280-milimeter atomic cannons that we hauled around Germany with a truck. It fired nuclear shells. It was a huge, long thing. We also had smaller atomic weapons called Davy Crockett’s. They looked like bazookas and were mounted on jeeps. It was an absolutely silly weapon with a couple of miles’ range.

It all seems so unimaginable now.

The word nuclear was, in 1961, magic and all the services had to have their own nuclear programs. And once you had a nuclear weapons program, you had to have all ranges. So that’s what containment looked like.

What role did military strength play in winning the Cold War?

It was crucial. It made it clear to the Soviets that there would be no walk in the woods and there would be war if they ever tried to come to Western Europe. Now we can wonder whether we could have stopped them, and whether they had the military capabilities we attributed to them.

What did you think of your enemy – and know about them?

In 1986, I was promoted to Lieutenant General and given command of the 5th United States Corps in Germany. I was back at the same Fulda Gap, except now I had 75,000 soldiers under my command and not 40. The mission remained unchanged for more than three decades: don’t let the Russian army come through. My job was to stop an organization called the 8th Guards Army, headed by General Achalov. I researched him very carefully. He was a paratrooper who had been injured, and they made him commander of an armored unit. I kept his picture on my desk and I used it to brief congressmen who were visiting and wanted to know why I needed so much money. Rather than give a PowerPoint presentation, which hadn’t been invented in those days, I would just point at the picture and say, “There’s the reason – Achalov. He’s one hour away with the 8th Guards Army and behind him, there are three other armies stacked up.”

Could you have stopped them?

Not without nuclear weapons, which we would have had to use by the third day and then we would have been off and running in a nuclear world war. The Soviets knew that, too. The generals on both sides knew, deep down in their hearts, “This can never be allowed to happen.”

How are the challenges today different than they were during that period?

In my early years of military service, I was involved in contests that were about containment and military superiority and regional wars – Korea, Vietnam. The most powerful trend right now is not so much a political trend or a military trend. It’s about economics and the creation of wealth. The nations that are increasingly successful in the world are those that are doing something about creating wealth. We are experiencing the greatest explosion of advancement in the middle class throughout the world that the world has ever seen. Hundreds of millions of Chinese who rode the same bicycles and wore the same clothes and hoped they might have a sewing machine in their lives are now in the middle class. That changes everything. The weapon of the future is education, and what’s most important now is properly educating our young people for our new challenges.

What happens with China? Does China become our enemy in this new world?

Absolutely not. What did they get from being our enemy before? They get much more out of selling us goods at Wal-Mart. It makes no sense to them to become our enemy. Yet in one of the greatest historical ironies in all of recorded history, a so-called undeveloped country is financing the profligacy of the largest, most powerful country in the world. And where do they get the money to buy our paper? By selling us stuff at Wal-Mart.

It’s incredible.

In this new world, what’s the role of NATO? Of military power?

It’s hard to close down a club when people keep asking for membership applications. I’m a big Atlanticist. I’m a supporter of NATO, but NATO has to adapt to the times. It will also be difficult to guide because it is a group of democracies. Yet it’s given us a level of interoperability that other groups of countries lack that we can use when we want to act together. When we wanted to help the Kurds in northern Iraq, we could work off the same maps and use the same procedures. The same was true when we fought the Gulf War. We didn’t have to train anybody to a new system of command and control because we took the European war and brought it to the desert. Desert Storm was nothing more than the battle we were planning to fight with the Soviets, except with no trees and no hills.

Did we miss a chance to more deeply integrate the Russians after the Cold War? Must we bear part of that blame?

It was extremely difficult and tricky to figure out what to do with respect to the new Russian Federation after the Cold War. We had to be very careful in expanding NATO in ways that did not provoke the Russians. But we did not make serious mistakes because the Alliance is enlarged there and Russia is not our enemy.

Was enlargement of NATO a good idea?

I don’t think we had a choice. Will you say to these newly freed countries that you’ve closed down NATO? No, we did the right thing by saying you have to meet our standards and then you can come in.

What do we do now about Russia – and about Georgia and Ukraine in that context?

We need to show the Russians more respect – and at the same time press them on the issues we consider important. I would move very, very carefully on Georgia and Ukraine, which aren’t ready for entry into NATO at this point. We also need to understand that Russia has far less capability to be a threat to anybody. Russia is one-half the size of the Soviet Union. It has an ageing and declining population through normal demographic attrition – because of bad healthcare, too much drinking, too much smoking, and low birth rate. They don’t have what we have that keeps our system vibrant, and that’s immigration. They are an energy provider and natural resource provider, but if you go to Kmart or Wal-Mart, you’re not going to see any Russian products. Twenty years after the Cold War, they don’t make anything anybody wants except gas, oil and minerals.

What concerns you most about the future?

What I’m not worried about is a world war. What I’m not worried about is a return to some superpower military contest because there are no longer any peer threats to the United States of America. I am worried about the instability we see manifested in places like Iraq, Afghanistan, North Korea and Iran. I think the Alliance has a role to play in dealing with these kinds of issues. I am deeply concerned about poverty throughout the world. I am concerned about infectious diseases. I am concerned about all the various problems that create failed states and the angry people that produces. It takes more money, and it takes more considered judgment. The Atlantic Community would do well to redirect more of its energies to these issues.

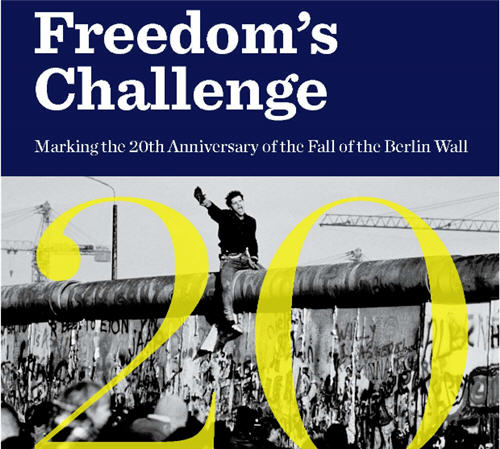

Frederick Kempe is president and CEO of the Atlantic Council. This interview is from Freedom’s Challenge, an Atlantic Council publication commemorating the 20th anniversary of the fall of the Berlin Wall.

Image: freedoms-challenge-cropped.jpg