The tariff two-step continues. On Monday morning in Geneva, negotiators from the United States and China announced a dramatic de-escalation to their trade war. As talks continue for the next ninety days, the United States will lower its tariffs on Chinese goods from 145 percent to 30 percent, while China will reduce its tariffs on the United States from 125 percent to 10 percent. The news sent global markets soaring, but plenty of uncertainty remains. What does this move mean for the United States, China, and the rest of the world? Our experts explain it all below, duty-free.

Click to jump to an expert analysis:

Melanie Hart: It looks like China has the upper hand in trade talks with the US

Josh Lipsky: Treating US-China trade like a light switch will cause it to short circuit

Hung Tran: The agreement is overshadowed by the possibility of abrupt change

It looks like China has the upper hand in trade talks with the US

The big takeaway from the weekend’s US-China meetings: Washington blinked, and Beijing decided to take the easy offramp on offer.

It is no accident that these talks occurred just as Walmart and other major US retailers ramped up their warnings to the administration to prepare for COVID-19 pandemic-level shortages. Shortages were already showing up in shipping and port data. Consumer retail shelves were coming up next. And there is zero indication that US consumers are willing to experience shortages reminiscent of the Great Depression to accommodate a trade war with unclear aims.

Meanwhile, Beijing was managing the economic fallout on the other side of the Pacific. Exports pivoted from the United States to Southeast Asia (likely the first step in a route designed to circumvent US tariffs). Many Chinese citizens praised President Xi Jinping for standing up to US bullying. Those that did not were censored.

From Beijing’s perspective, China now has what it wants with all US administrations: a negotiation process. And it didn’t give up anything of value to get it. At home, Xi secured strongman bona fides for standing up to US President Donald Trump and a new boogeyman to blame for China’s domestic economic woes. Globally, Xi gains points for looking like the rational actor willing to come to the table and seek a deal. Beijing has been trying to engage the United States in talks over fentanyl for months. China issued a white paper back in March laying out its efforts to crack down on fentanyl. Politically, as of May, we are now back where we started at the beginning of the second Trump administration, with one major change: the United States and China are now actively engaged in trade negotiations, and it feels like China has the upper hand.

—Melanie Hart is the senior director of the Atlantic Council’s Global China Hub and a former senior advisor for China at the US Department of State.

Treating US-China trade like a light switch will cause some short-circuiting

This was a massive, unexpected, and very welcome de-escalation. We can cite gross domestic product statistics and market reactions, but the real driver from the US side was the prospect of missing backpacks, sneakers, and T-shirts at Walmart and Target just as parents start back-to-school shopping.

China had a similar sense of urgency. Layoffs across ports and factories in southern China were becoming widespread. Apparently, the Chinese came into the negotiations ready to address nearly all the complaints the United States had raised and did so in a way that made US Treasury Secretary Bessent and US Trade Representative Jamieson Greer believe it was a genuine show of good faith.

Now the hard part starts—getting to a Phase Two trade deal. Inside the Trump administration, there is confidence that it can happen in ninety days. But the US-China trade deal signed during Trump’s first term took two years to negotiate—from 2018 to 2020—and this one is more complex and will address fentanyl, technology, semiconductors, and more. In the meantime, the Trump administration is going to introduce new tariffs, including on pharmaceuticals.

Treating the relationship between the world’s two largest economies like a light switch is going to cause some short-circuiting. Expect a new surge of imports in June and July as retailers try to get ahead of whatever the fall may bring—it’s very difficult to run a global economy with this kind of uncertainty.

The deal may be especially concerning for Europe. While Europe avoided the onslaught of cheap Chinese goods redirected to their shores, the United States is still on the hunt for revenue generators to offset the cost of Trump’s domestic priorities, including tax cuts. With China’s tariffs at least temporarily slashed and the negotiations with the European Union (EU) not gaining any traction, this puts Brussels in the hot seat.

—Josh Lipsky is the chair of international economics at the Atlantic Council, senior director of the GeoEconomics Center, and a former adviser to the International Monetary Fund (IMF).

The tariff suspension creates a powerful incentive for third countries to choose a side

The great global trade rebalancing of 2025 continues to gather momentum, illustrating that asymmetric negotiation is effective for counterparts seeking strategic shifts. The time horizon for tariff policy uncertainty has now extended to mid-August, aligning neatly but unfortunately with likely US fiscal policy constraints and the US budget process. The concessions by both China and the United States this weekend extend far beyond the headline temporary tariff reductions.

Both parties have now publicly acknowledged that the Bretton Woods structure for creating economic interdependence continues to create powerful incentives for de-escalation; neither China nor the United States (much less the rest of the world) can afford to pursue long-term decoupling and trade diversion. This is the most positive signal that emerged from Switzerland over the weekend.

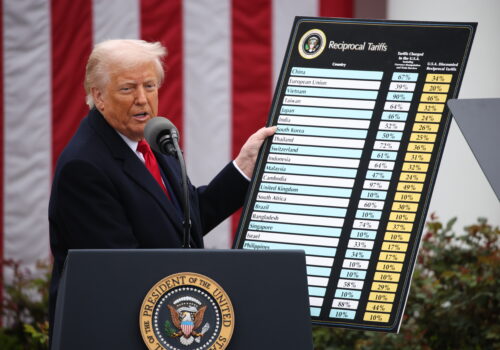

Both parties also now tacitly agree that the trade imbalances created over the course of the last few decades must be addressed. China effectively had no choice: the last sixty days have seen a range of entities (the EU, the World Trade Organization, and the United Kingdom) publicly agreeing with the United States’ list of grievances against the multilateral trading system articulated in Trump’s executive order establishing high reciprocal tariffs.

The ninety-day reprieve creates incentives for both the United States and China to build new bilateral trade arrangements with third countries to solidify their respective bargaining positions.

The tariff suspension also creates powerful incentives for those third countries to choose a side. The recently concluded US-UK framework agreement and ongoing US negotiations with other large trading partners (including India, Japan, Canada, Mexico, and the EU) is mirrored by ongoing Chinese efforts to solidify the economic heft and geoeconomic stature of the BRICS economies. South Africa, as president of the Group of Twenty (G20) this year, has maintained a studious silence. India’s negotiations with the United States display potential fissures within BRICS, even as Brazil and Russia increase their economic ties with China.

The current global trade policy volatility thus ironically replicates the parallel structure of negotiations that occurred in Bretton Woods, New Hampshire, eighty years ago. The great powers of the day gathered in the Gold Room to strike what we today would call “plurilateral” deals that set the boundaries of the possible even as broader negotiations in plenary sessions proceeded in the ballroom. Both then and now, the great powers of the day engaged in straight talk and struck difficult bargains for the purpose of setting a new economic equilibrium. The composition of participants in today’s Gold Room may be different, but the negotiating dynamic remains the same. The outcome will also achieve the same overall purpose: to restructure the geoeconomic balance of power. One can only hope that the deals struck over the next few months prove to be as durable as the original Bretton Woods agreement.

—Barbara C. Matthews is a nonresident senior fellow with the Atlantic Council. She is also CEO and founder of BCMstrategy, Inc and a former US Treasury attaché to the European Union.

Whatever the outcome of talks, tariff unpredictability will reduce US trade dependence on China

There are three major takeaways from this morning’s announcement of a temporary agreement between the United States and China: First, it is added proof that the Trump administration’s trade policy is less about the tariffs per se (or decoupling, in the case of China) than it is about achieving the objectives behind the tariffs. These objectives include curbing nonmarket excess capacity and other nonmarket policies and practices, unfair trade barriers abroad, and the goods trade deficit. Broad tariffs are ready and powerful tools for achieving these objectives, but they are also crude ones that inflict self-harm and are therefore less desirable than other arrangements with equivalent effect.

Second, trading partners that immediately started negotiations over these objectives instead of retaliating are in as good a position as, if not better than, China, which chose a hardline retaliatory stance. The former are in negotiations with the United States, as China is now, but without the severe economic harm inflicted by the retaliation in the interim.

Third, the United States and China are now in a position similar to that before China received “permanent normal trade relations” status and joined the World Trade Organization, when the trading relationship was subject to the uncertainty of yearly most favored nation status renewal. There was significant trade between the United States and China in this period, but it was hobbled by the unpredictability of the tariff regime. Regardless of the ultimate outcome of this morning’s agreement in terms of tariff levels, the unpredictability in the tariff regime will continue to serve the Trump administration’s objective of reducing trade dependence on China.

—L. Daniel Mullaney is a nonresident senior fellow with the Atlantic Council’s Europe Center and GeoEconomics Center. He previously served as assistant US trade representative for Europe and the Middle East.

The agreement is overshadowed by the possibility of abrupt change

The United States and China have agreed to reduce their respective bilateral tariffs on each other for the next ninety days, buying time to negotiate a trade deal. Essentially, the 145 percent tariffs the United States levied on China will be cut to 30 percent, and China’s 125 percent tariffs on US goods will be cut to 10 percent. The agreement has eased tension between the two countries and triggered major rallies in international equities, as well as the dollar, which had been under selling pressure.

While the reduction of tariffs and commitment to negotiate a trade deal between the world’s two largest economies is to be welcomed, these steps have raised important questions for the international trading system. First, this deal together with the recent US-UK trade agreement have confirmed that the world has moved into a bilaterally managed trading system based on reciprocity—with no references to previously agreed multilateral rules nor the World Trade Organization. Second, the agreements were made in a rather casual manner, without being codified into trade treaties or national laws. This adds to the uncertainty about how robust and sustainable those agreements can be, as they are overshadowed by the possibility of abrupt change. Finally, even with those agreements, US tariffs on other trading counterparts will likely remain higher than before April 2025. It appears that the global 10 percent tariff rate will become the floor tariff rate on imports by the United States.

Taken together, these developments elevate uncertainty, unpredictability, and complexity in the world trading order. They are likely to reduce trade volumes, especially shipments to the United States, which aims to cut its trade deficit. If trade among the rest of the world doesn’t increase enough to compensate, the decline in global trade will contribute to a weakening of global growth prospects.

—Hung Tran is a nonresident senior fellow at the GeoEconomics Center and former IMF official.

Further reading

Mon, May 12, 2025

What to make of the respite in the US-China trade war

Fast Thinking By

After the United States and China announced they will temporarily reduce tariffs, our experts are decoupling the signal from the noise of this major de-escalation.

Fri, Apr 25, 2025

Russia was spared from Trump’s ‘reciprocal’ tariffs. This should change.

New Atlanticist By Olivia Yanchik

The volume of US-Russia bilateral trade, although low, is still markedly higher than that of other countries that have fallen under the Trump administration’s reciprocal tariffs.

Thu, Apr 10, 2025

What to expect as Trump’s trade war zeroes in on China

Fast Thinking By

On April 9, US President Donald Trump announced that he would suspend many of his “liberation day” import tariffs—but he raised the tariff on China to 145 percent.

Image: U.S. Secretary of the Treasury Scott Bessent and U.S. Trade Representative Jamieson Greer attend a news conference after trade talks with China in Geneva, Switzerland, May 12, 2025. REUTERS/Olivia Le Poidevin.