“An industrial revolution, an information revolution, and a renaissance—all at once.” That’s how the Trump administration describes artificial intelligence (AI) in its new “AI Action Plan.” Released on Wednesday, the plan calls for cutting regulations to spur AI innovation and adoption, speeding up the buildout of AI data centers, exporting AI “full technology stacks” to US allies and partners, and ridding AI systems of what the White House calls “ideological bias.” How does the plan’s approach to AI policy differ from past US policy? What impacts will it have on the US AI industry and global AI governance? What are the implications for energy and the global economy? Our experts share their human-generated responses to these burning AI questions below.

Click to jump to an expert analysis:

Graham Brookie: A deliberative and thorough plan—but three questions arise about its implementation

Trey Herr: If the US is in an AI race, where is it going?

Trisha Ray: On international partnerships, the AI Action Plan is all sticks, few carrots

Nitansha Bansal: The plan is a step forward for the AI supply chain

Raul Brens: The US can’t lead the way on AI through dominance alone

Mark Scott: The US and EU see eye-to-eye on AI, up to a point

Esteban Ponce de Leon: The plan accelerates the tension between proprietary and open-source models

Joseph Webster: On energy, watch what the plan could do for the grid and batteries

A deliberative and thorough plan—but three questions arise about its implementation

We are in an era of increasing geopolitical competition, increased interdependence, and rapid technological change. No single issue demonstrates the convergence of all three better than AI. The AI Action Plan released today reflects this reality. Throughout the first six months of the Trump administration, officials have run a thorough and deliberative policy process—which White House officials say incorporated more than ten thousand public comments from various stakeholders, especially US industry. The resulting product provides a clear articulation of AI in terms of the tech stack that underpins it and an increasingly vast ecosystem of industry segments, stakeholders, applications, and implications.

The policy recommendations laid out in the action plan are well-organized and draw connections between scientific, domestic, and international priorities. Despite the rhetoric, there is more continuity than it may appear from the first Trump administration to the Biden administration to this action plan—especially in areas such as increasing investment in infrastructure, hardware fabrication, and outcompeting foreign adversaries in innovation and the human talent that underpins it. The AI Action Plan will continue to scale investment and growth in these areas. The key divergence is in governance and guardrails.

Three outstanding questions stick out regarding effective implementation of the Action Plan.

First, in an era of budget and staff cuts across the federal government, will there be enough government expertise and funding to realize much of the ambition of this plan? For example, cutting State Department staff focused on tech diplomacy or global norms could undercut parts of the international strategy. Budget cuts to the National Science Foundation could impact AI priorities from workforce to research and development.

Second, how will the administration wield consolidated power with frameworks to reward states it views as aligned and cut funding to states it sees as unaligned?

Third, beyond selling US technology, how will the United States not just compete against Chinese frameworks in global bodies, but also work collaboratively with allies and partners on AI norms?

Given the pace of change, the United States’ success will be based on continuing to grow the AI ecosystem as a collective whole and for the ecosystem to iterate faster to compete more effectively.

—Graham Brookie is the Atlantic Council’s vice president for technology programs and strategy.

If the US is in an AI race, where is it going?

The arms race is a funny concept to apply to AI, and not just because the history of arms races is replete with countries bankrupting themselves trying to keep up with a perceived threat from abroad. The repeated emphasis on an AI “race” is still ambiguous on a crucial point—what are we racing toward?

Consider this useful insight on arms racing in national security: “Over and over again, a promising new idea proved far more expensive than it first appeared would be the case; yet to halt midstream or refuse to try something new until its feasibility had been thoroughly tested meant handing over technical leadership to someone else.”

Was this written about AI? No, this comes from historian William H. McNeill writing about the British-German maritime arms race at the turn of the twentieth century. The United Kingdom and Germany raced to build ever bigger armored Dreadnoughts in an attempt to win naval supremacy based on the theory that the economic survival of seagoing countries would be determined by the ability to win a large, decisive naval battle. Industry played a key role in encouraging the competition and setting the terms of the debate, increasingly disconnected from the needs of national security

So, to take things back to the present, what are we racing toward when it comes to AI? The White House’s AI Action Plan hasn’t resolved this question. The plan’s Pillar 1 offers a swath of policy ideas grounded more in AI as a normal technology. Pillar 2 is more narrowly focused on infrastructure but still thin on the details of implementation. Tasking the National Institute of Standards and Technology is a common refrain and some of the previous administration’s policy priorities, such as the CHIPS Act and Secure by Design program have been essentially rebranded and relaunched. Pillar 3 calls for a renewed commitment to countering China in multilateral tech standards forums, a cruel irony as the State Department office responsible for this was just shuttered in wide-ranging layoffs announced earlier this month.

The national security of the United States and its allies is composed of more than the capability of a single cutting-edge technology. Without knowing where this race is going, it will be hard to say when we’ve won, or if it’s worth what we lose to get there.

—Trey Herr is senior director of the Cyber Statecraft Initiative (CSI), part of the Atlantic Council Technology Programs, and assistant professor of global security and policy at American University’s School of International Service.

On international partnerships, the AI Action Plan is all sticks, few carrots

The AI Action Plan’s strongest message is that the United States should meet, not curb, global demand for AI. To achieve this, the plan suggests a novel and ambitious approach: full-stack AI export packages through industry consortia.

What is the AI stack? Most definitions include five layers: infrastructure, data, development, deployment, and application. Arguably, monitoring and governance is a critical sixth layer. US companies dominate components of different layers (e.g. chips, talent, cloud services, and models). But the United States’ ability to export full-stack AI solutions, the carrot in this scenario, is limited by a rather large stick: its broad export control regime, which includes the Foreign Director Product Rule and Export Administration Regulations.

Governance remains the layer the United States is weakest on. The AI Action Plan does emphasize countering adversarial influence in international governance bodies, such as the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, the Internet Corporation for Assigned Names and Numbers, the Group of Seven (G7), the Group of Twenty (G20), and the International Telecommunication Union. However, the plan undermines the consensus-based AI governance efforts within these bodies, including an apparent jibe at the G7 Code of Conduct. If it seeks real alignment with allies and partners, the White House must outline an affirmative vision for values-based global AI governance.

—Trisha Ray is an associate director and resident fellow at the Atlantic Council’s GeoTech Center, part of the Atlantic Council Technology Programs.

The plan is a step forward for the AI supply chain

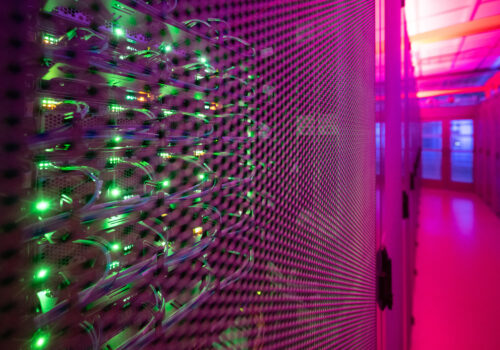

The AI Action Plan’s focus on the full AI stack—from energy infrastructure, data centers, semiconductors, and the talent pipeline to acknowledging associated risks and cybersecurity concerns—is welcome. The plan has adopted an optimistic view of the open source and open weight AI models, and it has built in provisions to create a healthy innovation ecosystem for open source AI models along with strengthening the access to compute—which is another positive policy realization on the part of the administration.

The administration appears to be cognizant that competitiveness in AI will not be achieved solely by domesticating the AI supply chain. Competitiveness in this ecosystem needs to be a multi-pronged strategy of translating domestic AI capabilities into national power faster, more efficiently, more effectively, and more economically than adversaries—driven by faster chips, smarter and more trustworthy models, a more resilient electricity grid, a robust investment infrastructure, and collaboration with allies.

This emphasis on securing the full stack means that the near-term policy will target not just innovation, but the location, sourcing, and trustworthiness of every component in the AI pipeline. The owners and users of AI supply chain components have much to look forward to. The new permitting reform could reshape the location of AI infrastructure; recognition of workforce and talent bottlenecks can lead to renewed focus on skill development and training programs; and emphasis on AI-related vulnerabilities in critical infrastructure could translate into more regular and robust information sharing apparatuses and incident response requirements for private sector executives.

In all, achieving AI competitiveness is an ambitious goal, and the plan sets the government’s agenda straight.

—Nitansha Bansal is the assistant director of the Cyber Statecraft Initiative.

The US can’t lead the way on AI through dominance alone

The AI Action Plan makes one thing clear: the United States isn’t just trying to win the AI race—it’s trying to engineer the track unilaterally. With sweeping ambitions to export US-made chips, models, and standards, the plan signals a cutting-edge strategy to rally allies and counter China. But it also takes a big gamble. Rather than co-design AI governance with democratic allies and partners, it pushes a “buy American, trust American” model. This will likely ring hollow for countries across Europe and the Indo-Pacific that have invested heavily in building their own AI rules around transparency, climate action, and digital equity.

There’s a lot to like in the plan’s push for infrastructure investment and workforce development, which is a necessary step toward building serious AI capacity. But its sidelining of critical safeguards and its dismissal of issues like misinformation, climate change, and diversity, equity, and inclusion continues to have a sandpaper effect on traditional partners and institutions that have invested heavily in aligning AI with public values. If US developers are pressured to walk away from those same principles, the alliance could fray and the social license to operate in these domains will inevitably suffer.

The United States can lead the way—but not through dominance alone. An alliance is built on the stabilizing forces of trust, not tech stack supply chains or destabilizing attempts to force partners to follow one country’s standards. Building this trust will require working together to respond to the ways that AI shapes our societies, not just unilaterally fixating on its growth.

—Raul Brens Jr. is the director of the GeoTech Center.

On energy, watch what the plan could do for the grid and batteries

Two energy elements in the AI Action Plan hold bipartisan promise:

- Expanding the electricity grid. The action plan notes the United States should “explore solutions like advanced grid management technologies and upgrades to power lines that can increase the amount of electricity transmitted along existing routes.” In other words, advanced conductors, reconductoring, and dynamic line ratings (and more) are on the table. Both Republicans and Democrats likely agree that transmission and the grid received inadequate investment in the Biden years: The United States built only fifty-five miles of high-voltage lines in 2023, down from the average of 925 miles per year between 2015 and 2019. The University of Pennsylvania estimated that the Inflation Reduction Act’s energy provisions would cost $1.045 trillion from 2023 to 2032, but the bill included only $2.9 billion in direct funding for transmission.

- Funding “leapfrog” dual-use batteries. Next-generation battery chemistries, such as solid-state or lithium-sulfur, could enhance the capabilities of autonomous vehicles and other platforms requiring on-board inference. Virtually all autonomous passenger vehicles run on batteries, and the action plan mentions self-driving cars and logistics applications. Additionally, batteries are a critical military enabler: They are deployed in drones, electronic warfare systems, robots, diesel-electric submarines, directed energy weapons, and more. Given the bipartisan interest in autonomous vehicles and US military competition with Beijing, there may be scope for bipartisan agreement on funding “leapfrog,” dual-use battery chemistries.

—Joseph Webster is a senior fellow at the Atlantic Council’s Global Energy Center and the Indo-Pacific Security Initiative.

The US and EU see eye-to-eye on AI, up to a point

Despite the ongoing transatlantic friction between Washington and Brussels, much of what was outlined by the White House aligns with much what EU officials have similarly announced in recent months. That includes efforts to reduce bureaucratic red tape to foster AI-enabled industries, the promotion of scientific research to outline a democracy-led approach to the emerging technology, and efforts to understand AI’s impact on the labor force and to upskill workers nationwide.

Yet where problems likely will arise is how Washington seeks to promote a “Make America Great Again” approach to the export of US AI technologies to allies and the wider world. Much of that focuses on prioritizing US interests, primarily against the rise of China and its indigenous AI industry, in multinational standards bodies and other global fora—at a time when the White House has significantly pulled back from previously bipartisan issues like the maintenance of an open and interoperable internet.

This dichotomy—where the United States and EU agree on separate domestic-focused AI industrial policy agendas but disagree on how those approaches are scaled internationally—will likely be a central pain point in the ongoing transatlantic relationship on technology. Finding a path forward between Washington and Brussels must now become a short-term priority at a time when both EU and US officials are threatening tariffs against each other.

—Mark Scott is a senior resident fellow at the Digital Forensic Research Lab’s Democracy + Tech Initiative within the Atlantic Council Technology Programs.

The US plan may sound like those of the UK and EU—but the differences are critical

The new AI Action Plan—like its peers from the European Union (EU) and the United Kingdom—is focused on “winning the AI race” through regulatory actions to direct and promote innovation, new investments to create and advance access to crucial AI inputs, and frameworks for international engagement and leadership. Winning the AI race is, in effect, the top priority of all three AI plans, albeit in different ways. While the EU’s AI Act wants to be the first to create regulatory guardrails, the United States’ AI plan has a strong deregulation agenda. In a significant break from other policy measures from this administration to ensure US dominance, this action plan moves away from a purely domestic orientation to the international sphere, flexing the reach of traditional US notions of power. This includes international leadership in frontier technology research and development and adoption, as well as creating global governance standards. It’s a testament to the scarcity, quality, and sizable nature of the inputs needed for global AI dominance that even the Trump administration is thinking through its strategy on AI in terms of global alignment.

Even as each jurisdiction, including the United States, seeks to position itself as the dominant player in the AI race, there is no common scoreboard for deciding a winner for the game. Each player has devised an ambitious but distinct understanding of this “competition,” and each competition will play out through harnessing a unique combination of industrial, trade, investment, and regulatory policy tools. As the race unfolds in real time, the challenge for US policymakers is to simultaneously create the rules of the game while playing it effectively. A broad range of stakeholders, including AI companies, investors, venture capitalists, safety institutes, and allied governments seek clarity and stability. They all will watch the implementation of the US plan closely to determine their next moves.

There are two encouraging signs in this action plan when it comes to strengthening US competitiveness:

First, by prioritizing international diplomacy and security, the United States is positioning itself to influence the global AI playbook that will ultimately determine who reaps economic benefits from AI systems. Leading multilateral coordination on AI positions the United States to secure open markets for AI inputs, shape global adoption pathways, and protect its private sector from regulatory fragmentation and protectionism.

Second, the plan creates a roadmap for ensuring that the United States and its allies assimilate AI capabilities faster than their adversaries. In this vein, the plan emphasizes the importance of coordinating with allies to implement and strengthen the enforcement of coordinating export controls.

—Ananya Kumar is the deputy director for Future of Money at the GeoEconomics Center.

—Nitansha Bansal is the assistant director of the Cyber Statecraft Initiative.

The plan accelerates the tension between proprietary and open-source models

The White House’s AI Action Plan explicitly frames model superiority as essential to US dominance, but this creates profound tensions within the US ecosystem itself. As better models attract more users—who, in turn, generate training data for future improvements—we may see a self-reinforcing concentration of power among a few firms.

This dynamic creates opportunities for leading firms to set safety standards that elevate the entire industry. A clear example is Anthropic’s “race to the top,” where competitive incentives are directly channeled into solving safety problems. When frontier labs adopt rigorous development protocols, market pressures force competitors to match or exceed these standards. However, the darker side of innovation may emerge through benchmark gaming, where pressure to demonstrate superiority incentivizes optimizing for benchmarks rather than genuine capability, risking misleadingly capable systems that excel at tests while lacking true innovation.

Yet the AI Action Plan’s emphasis on open-source models highlights a more complex competitive landscape than market concentration alone suggests. Open-source strategies are not just defensive moves against domestic monopolization; they also represent offensive tactics in the global AI race, particularly as Chinese open-source models gain traction and threaten to establish alternative standards with millions of users worldwide.

This dual-track competition between concentrated proprietary excellence and distributed open-source influence fundamentally redefines how firms must compete.

Success now requires not only racing for capability supremacy but also strategically deciding what to keep proprietary and what to release in order to shape global standards. The plan’s call to “export American AI to allies and partners” through “full-stack deployment packages” suggests that the ultimate competitive advantage may lie not in the superiority of a single model, but in the ability to build dependent ecosystems where US AI becomes the essential infrastructure for global innovation.

—Esteban Ponce de León is a resident fellow at the DFRLab of the Atlantic Council.

Further reading

Mon, Jul 21, 2025

Navigating the new reality of international AI policy

GeoTech Cues By Evi Fuelle, Courtney Lang

To reach their goals of national AI adoption, governments must continue to advance the global policy discussion on trust, safety, and evaluations.

Fri, Jul 18, 2025

Ground-zero for the US AI energy challenge: A state-level case study

EnergySource By Andrea Clabough

Virginia's AI data center boom could double the state's power demand within a decade, forcing residents' electricity bills higher. But with careful planning and partnerships, policymakers can balance energy, economic, and emissions goals.

Sun, Jun 15, 2025

Why tariffs on AI hardware could undermine US competitiveness

New Atlanticist By Joseph Webster, Jessie Yin

Tariffs targeted at China have their uses in the US-China tech competition, but they shouldn’t be applied haphazardly to US allies and partners.

Image: An aerial view shows construction underway on a Project Stargate AI infrastructure site, a collaboration between three large tech companies – OpenAI, SoftBank, and Oracle - in Abilene, Texas, U.S., April 23, 2025. REUTERS/Daniel Cole.