While social media companies have taken some initial steps toward tackling the problem of disinformation on their platforms, democratic governments “shouldn’t just be reliant on the fact that Facebook or Google may or may not be doing a good job” identifying or eliminating misleading or harmful content, according to UK Member of Parliament Damian Collins. Right now, Collins argued, governments “only have their word” as evidence that social media companies are adequately addressing the disinformation threat.

Collins, speaking on March 8 at the Atlantic Council Disinfo Week event in Brussels, Belgium, argued that governments need to have more oversight and control over how social media companies are curating and monitoring intentionally misleading or harmful content on their platforms. “We shouldn’t be reliant on the goodwill of the tech companies to say they will introduce these policies,” he argued, adding that governments should “want the right to check” if companies are really addressing the problem.

Collins chairs a parliamentary committee in the United Kingdom on the issue of disinformation and in December 2018 released e-mails from major social media companies which detailed the platforms’ ability to access user data. Collins’ committee released a report on February 18 that accused Facebook of “intentionally and knowingly” violating data privacy laws.

Nicholas Vincour, technology editor for POLITICO, noted at the March 8 event that there have been several significant actions taken by social media companies in the last few weeks, including Facebook’s decision to deemphasize and block ads for anti-vaccination misinformation, Google’s banning of political ads in Canada, and Facebook’s removal of fake pages and harmful content in the United Kingdom and Romania. While Vincour suggested that this could be “self-regulation in action,” Collins argued that the actions address just “the tip of the iceberg.”

Google and Facebook, Collins said, “are offering up a small number of these actions every now and again to make it look like they acknowledge the fact that this might be a problem and they are doing something about it.” Government regulation is needed, Collins argued, in order to make sure that social media companies are doing all they can to stop the spread of harmful or misleading content.

Jens-Henrik Jeppesen, representative and director for European affairs at the Center for Democracy and Technology, cautioned that overregulation of social media companies could do more harm than good. The ability for users to post content freely on online platforms without prior verification or content controls, Jeppesen explained, has been an enshrined principle since the early days of the Internet. “Had we not had this principle embedded in law,” he said, “we would not have seen the growth of the Internet and Internet-based services in the way that we have.”

Moves toward strict content controls could raise costs for smaller emerging platforms as well, warned Alina Polyakova, the David M. Rubenstein fellow for foreign policy at the Brookings Institution. At a time when uncensored social media companies are facing increased competition from controlled Chinese platforms such as Tik Tok and WeChat, Polyakova worries that democracies could now “regulate the hell out of [social media] companies and in the end lose the competitive advantage, vis-à-vis authoritarian regimes, especially China.”

Suggestions that social media companies should bear more responsibility for the content on their platforms also raises concerns that overregulation could dangerously undermine the freedom of speech. “We need to be able to regulate in a way that still protects these spaces for free expression,” Melanie Smith, a cyber intelligence analyst with Graphika, said.

Bret Schafer, a social media analyst and communications officer from the German Marshall Fund’s Alliance for Securing Democracy, warned that tight controls could play right into the hands of authoritarian regimes. “If we overregulate, if we over-moderate, that is going to give [Russian state outlet] RT a headline story every time…If we don’t have clear standards, if we don’t have clear justification for why actions are taken, that’s going to be a propaganda win every single time,” Schafer said.

Collins said he understood the concerns that content should not itself be regulated, but he argued that regulation should be aimed at how platforms are distributing the content on their sites. Social media companies are not just bulletin boards where people can put whatever they want up, Collins explained. “They curate the content. They are selecting for their customers content they think they want to see,” he said, suggesting that this curation makes the companies liable for the promulgation of harmful or misleading content.

Polyakova agreed that distribution of content should be the target for regulators, saying that “the root of the [disinformation] problem is not about the content, it is about the network diffusion that cuts across platforms.” She specifically pointed to the continued presence of Russian state media outlet RT in the top search results for Google as an example where government should force tech companies to change their algorithms for pushing content to users. Collins said electoral laws in the United Kingdom forcing financial disclosure statements on all print and mail electoral advertisements and content guidelines for TV broadcasters are precedents for how to regulate content dissemination without censorship.

For Collins, though, inaction against the disinformation problem is unacceptable. “If there are networks spreading disinformation…or other people who are spreading messages of hate,” he said, “we should see that as a challenge to society and to the way our democracies function.”

David A. Wemer is assistant director, editorial at the Atlantic Council. Follow him on Twitter @DavidAWemer.

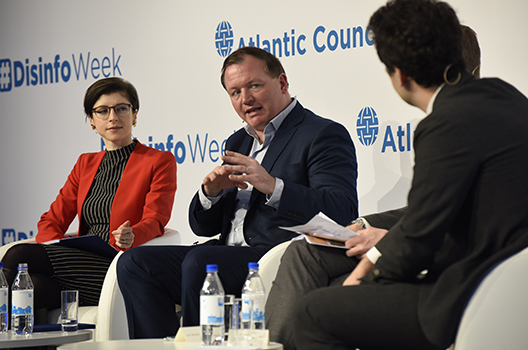

Image: From left, Brookings Institution David M. Rubenstein Fellow for Foreign Policy Alina Polyakova, UK Member of Parliament Damian Collins, Center for Democracy and Technology Director for European Affairs Jens-Henrik Jeppesen, and POLITICO Technology Editor Nicholas Vincour, speak at the Atlantic Council Disinfo Week event in Brussels, Belgium on March 8, 2019.