Despite US Congressional efforts to modernize and secure election system infrastructure across the country, beginning in 2002 with the Help America Vote Act (HAVA) and emergence of the Election Assistance Commission (EAC), Russian government hackers have gained access to systems that represent America’s most cherished institution—the democratic vote. Within a campaign of disinformation, fake social media accounts, and state-run media narratives, Russia continues to target the US electoral process, according to US intelligence officials during a press conference at the beginning of August. These stark warnings come just after the Justice Department’s indictment of twelve officers of Russia’s military intelligence apparatus, the Glavnoe Razvedyvatelnoe Upravlenie (GRU), who hacked the Democratic National Committee (DNC), the Democratic Congressional Campaign Committee (DCCC), and election voter registration databases beginning in April of 2016.

How can lawmakers better secure the US election system as the 2018 midterms loom? Though progress has been made in election funding and assistance to states, the keys to election security are mandatory cybersecurity standards for election system vendors and for state and local election sites, in tandem with adequate state funding.

According to the indictment, hackers used spearphishing techniques to gain remote access to the DNC and DNCC servers using GRU-designed malware, X-Agent, a favorite tool of the hacker group Fancy Bear. The hackers also penetrated a US vendor of election software used to verify voter registration and gained access to at least twenty-one states’ election systems and voter registration databases to identify system vulnerabilities. GRU officials also searched for vulnerabilities on Georgia, Iowa, and Florida county websites in October of 2016, an activity likely ongoing given recent US officials’ statements.

The following month, the hackers targeted Florida election personnel using spearphishing attacks, which embedded malware into a Microsoft Word document sent via an email mimicking the previously-hacked election software vendor’s email address. In July of 2016, the Russians hacked one state’s election board, stealing thousands of voters’ personal information, while remaining anonymous by mining bitcoin to pay foreign companies to register websites for spearphishing attacks, and post leaked documents.

The indictment specifics are striking and highlight continuing election system vulnerabilities despite sixteen years of work by the EAC, established to assist states in upgrading election systems. The EAC does have a vendor election system certification process, but certification is only performed by state or vendor request and states are not required to use certified election systems. Further, though standards are established in collaboration with the National Institute of Science and Technology (NIST), systems are tested against 2005 standards in an era when technology advances in the blink of an eye.

The 2017 DEFCON Election Village hacking report exposed security flaws in vendor election systems, as discussed by Jeff Moss, DEFCON founder and Atlantic Council senior fellow. The report also revealed that voting machines used at DEFCON consisted of foreign-made parts, including hardware from China, raising more questions about vendor supply chain security and foreign involvement in election products. Reports also recently emerged that a Maryland election software vendor, ByteGrid LLC, was financed by an equity firm whose largest investor is Vladimir Potanin, former deputy prime minister of Russia, with ties to Russian President Vladimir Putin.

The Russian GRU’s probing of election websites and google searches reveal their intent to exploit outdated election equipment and software in a market dominated by few vendors, who have produced faulty equipment in the past. The New Mexico secretary of state testified during a recent House Oversight Committee Hearing that many local precincts in her state lack funds to update software and equipment, are understaffed, and have limited access to Department of Homeland Security (DHS) election security tools.

Even with adequate funding, states are limited in choosing an election system. ES&S, which once held almost 70% of the election system market, was sued for allegedly using election software in the 2012 US presidential election that was not certified by the battleground state of Ohio and produced voting machines that failed to cast 18,000 votes in a 2007 election.

To ensure the integrity of the electoral process, Congress must allocate election security funding for state and local governments and impose mandatory guidelines for election vendors. The election security funds established by HAVA appear to be insufficient, given that precincts continue to use outdated equipment and software and lack the ability to hire IT personnel or train staff in basic cybersecurity practices, as described in House Oversight Hearing testimony. Despite this testimony and a recent letter from US state attorney generals to Congress, lawmakers recently failed to pass an amendment increasing election security funding for states.

Though funding is crucial for election security, mandatory electoral guidelines addressing security of election systems and states’ electoral processes, including cybersecurity practices and mandatory election system audit trails, are key to reducing the threat of foreign electoral interference. The DHS secretary designated election sites as critical infrastructure in January of 2017 under the “Government Facilities Sector” of the Obama administration’s 2013 Presidential Policy Directive. The federal government should establish mandatory election equipment standards and require vendors to submit a software bill of materials.

State and local precincts could share information on security issues in a centralized location, such as the MS-ISAC. States should employ audits of precincts to determine whether prompt software updates and basic cybersecurity practices, such as password security measures, are employed by election officials. Further, election locations involved in the 2016 hack should undergo forensics to identify and remove malware present and all locations should employ vulnerability testing in collaboration with the private sector to further secure election sites.

As the midterms approach and reports of continuing Russian hacks on election infrastructure emerge, the United States must develop mandatory standards to ensure the security of the electoral process, from election equipment vendors to polling stations, in line with its designation as critical infrastructure. Although adequate election security funds and resources for states is imperative, America’s democratic processes will remain vulnerable to foreign cyberattacks without mandatory standards to ensure election system security.

Heather Regnault is a Cyber Statecraft Initiative Intern at the Atlantic Council and is pursuing a Ph.D. in International Affairs with a focus on national security and cybersecurity at the Georgia Institute of Technology.

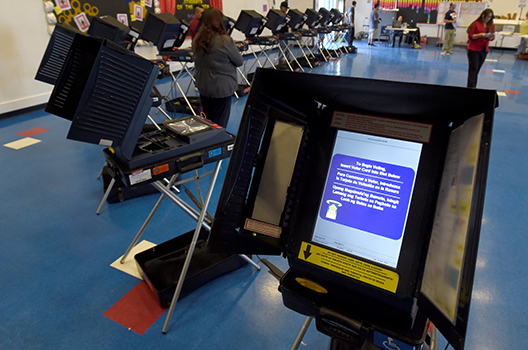

Image: Voting machines are set up for people to cast their ballots during voting in the 2016 presidential election at Manuel J. Cortez Elementary School in Las Vegas, Nevada, U.S, November 8, 2016. (REUTERS/David Becker)