While the end of the Cold War signaled a victory for the forces of democracy, today’s global setting is in flux and democracy faces an uncertain future. Democracy assistance no longer consists of consolidating pro-democracy movements through training, capacity building and technical support. Current challenges require new approaches that are more responsive and relevant, especially in the Arab and Muslim world where extremists reject democracy as a Western construct. The U.S. should not falter from championing democracy. Not only is democracy the best system of governance to realize human potential, it also advances U.S. national security by providing a political alternative to those who might otherwise mistakenly conclude that they can advance their aspirations through sensational violence.

Critics of U.S. democracy assistance at home and abroad point to the Iraq War, where the promotion of democracy was used to justify military action post-facto. Even authoritarians who are friendly to the United States resent calls for democracy, insisting that democracy assistance is really a Trojan horse for undermining regimes that are hostile to America’s interests. They justify their resistance to democratization efforts as defense of national sovereignty and protection from foreign intervention. They label democracy activists who receive political or financial support from the United States as stooges of the West.

U.S. opponents of democracy are also cynical about America’s motives. They question America’s commitment to the rule of law, pointing to Abu Ghraib, Guantanamo, and the rendition of suspects to countries that torture. In addition, they are quick to criticize the U.S. for turning a blind eye to the abuses of its autocratic allies.

Democracy assistance typically focuses on constitutional arrangements protecting and promoting individual and minority rights. It often emphasizes electoral assistance and measures to strengthen political parties, independent media and civil society. This is anathema to political Islam, which emerged in the 20th century as an effort by fundamentalists to address challenges of the modern world. Rejecting innovation, they believe that any Muslim who deviates from Shari’a, the strict interpretation of Islamic law, is impure. Linking piety with an end to political corruption and misrule, they reject constitutional democracy as the basis for secular government that empowers human rulers over the law of God.

Iran’s President Mahmoud Ahmedinejad is the primary proponent of this radical political theology. He maintains that Islam and democracy are fundamentally incompatible: “Liberalism and Western-style democracy have not been able to realize the ideals of humanity. Today, these two concepts have failed. Those with insight can already hear the sounds of the shattering and fall of the ideology and thoughts of liberal democratic systems.” (Open letter to President George W. Bush, May 2006).

While Ahmedinejad believes that democracy represents the secularization of Christian and Western values and therefore lacks universal appeal, many Muslims reject fanaticism, citing Islam’s traditions of pluralism, cosmopolitanism, and open-mindedness. Hundreds of millions of Muslims live in democratic countries, either as minorities or majorities in countries ranging from Turkey and Indonesia to Western Europe, and enjoy democratic freedoms. They maintain that the Islamic process of consultation is entirely consistent with democratic debate. The democracy deficit in the Arab and Muslim world is more a problem of supply than demand.

At this pivotal moment, the Obama administration would be well advised to reflect on America’s Cold War experience and garner guiding principles for democracy assistance to the broader Muslim community. These principles proceed from the recognition that America’s role should be to stand behind, not in front of democracy movements. The U.S. should not “lead” or “teach” democracy. It is most effective as a catalyst for change. To this end, patience is required; democratization is a process, not an event. Overheated rhetoric risks discrediting pro-democracy activists by making them appear as agents of a foreign power. The U.S. must tread softly; reform is ultimately driven by the societal demand of local stakeholders.

There is, today, a moment of opportunity. It flows from President Barack Obama’s Cairo speech (June 4, 2009), which fundamentally shifted the dynamic between Western and Muslim societies:

“I have come here to seek a new beginning between the United States and Muslims around the world; one based upon mutual interest and mutual respect; and one based upon the truth that America and Islam are not exclusive, and need not be in competition. Instead, they overlap, and share common principles – principles of justice and progress; tolerance and the dignity of all human beings.”

Without the U.S. to blame for their societal ills, voters in the Arab and Muslim world are increasingly holding their leaders accountable. Soon after Cairo, Lebanese voters balked at a coalition including Hezbollah; Iranians voted overwhelmingly for reform candidates (according to exit polls); and Indonesia returned its secular president to power in the first round.

Reversing negative perceptions of the U.S. will require skillful public diplomacy. But restoring America’s credibility requires substance as well as spin. Policies must both advance U.S. national interests and reflect favorably on America’s intentions. Successful democracy assistance should be based on broader, value-based principles such as safeguarding rights and enhancing human capital through formal education systems and economic development.

In Cairo, President Obama spoke compellingly about assisting the democratic aspirations of people for democracy, freedom and justice. While his words were welcomed, the U.S. will be judged by what it does and not by what Obama says. First and foremost, restoring U.S. credibility requires more balanced and effective U.S.-led efforts aimed at realizing a viable state of Palestine alongside a secure state of Israel.

Reaching out to those directly affected by democracy assistance is also critical to restoring credibility. Right after President Obama’s Cairo speech, 30 U.S. embassies surveyed civil society in countries that are part of the Arab and Muslim world to seek their views on programmatic approaches to implementing the so-called Cairo principles. The White House also launched an inter-agency task force and established a fund to support activities. The Obama administration deserves credit for “walking the talk” and dedicating resources to democracy assistance at a time when budget priorities are constrained by the financial crisis and the costs of engagement in Iraq and Afghanistan.

Democratization of the broader Muslim community is a generational endeavor that requires international cooperation. The U.S. can leverage its democracy assistance by working with other countries and international organizations. European countries, as well as the UN, EU, OSCE and others have important roles to play supporting elections and governance. As was the case during the Cold War, democratizing the broader Muslim community will require vision and U.S. leadership. The Obama administration is off to a good start, but if there is one lesson from the Cold War it is the need for patience and partnership, with both the international community and those on the front-lines of democratic change.

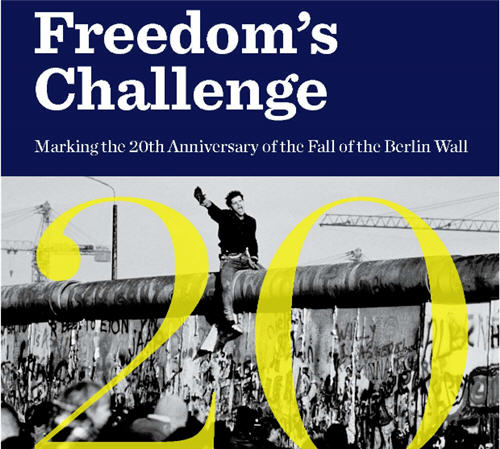

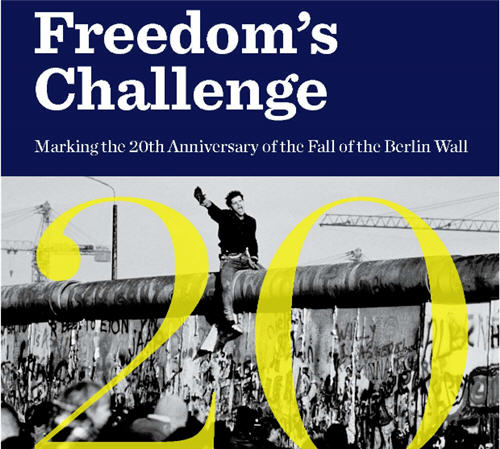

David L. Phillips is Director of the Program on Conflict Prevention and Peacebuilding at American University in Washington D.C. His most recent book is From Bullets to Ballots: Violent Muslim Movements in Transition. This essay is from Freedom’s Challenge, an Atlantic Council publication commemorating the 20th anniversary of the fall of the Berlin Wall.