Trump in Southeast Asia: Cease-fire, ceremonies, and the limits of regional diplomacy

US President Donald Trump kicked off his stretch of Asian summitry on Sunday in Malaysia, where he joined Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) leaders for their biannual summit. Trump’s visit drew new global attention on this nearly sixty-year-old institution, but with the summit now complete and the media having moved on, its shortcomings are once again laid bare. ASEAN can make diplomatic progress and put on a good show, but the group’s underlying tensions and often divergent goals remain unresolved.

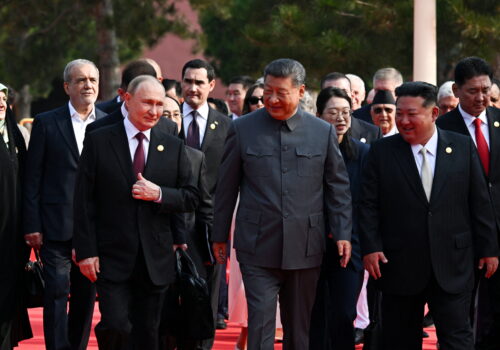

This week was the second time Trump has participated in the summit, following a visit to the Philippines in 2017 during his first term. In Kuala Lumpur, Trump announced trade deals with Thailand, Cambodia, and Malaysia, but the primary reason he was there was to preside over the main event of the summit—the signing ceremony for a cease-fire agreement between Thailand and Cambodia.

The two countries were engaged in hostilities throughout the summer over a century-old dispute involving a temple and the surrounding area along their shared border. A truce was brokered in late July by Malaysia, following a critical intervention by Trump, who personally called the leaders of both nations and threatened to cut off trade negotiations if they didn’t agree to a cease-fire.

The Thailand-Cambodia cease-fire

The cease-fire signing ceremony was carefully choreographed to generate multiple diplomatic wins. For Trump, presiding over the signing ceremony provided an early diplomatic highlight for his Asia trip—and a boost for his self-proclaimed campaign for a Nobel Peace Prize. His insistence that China be excluded from the signing ceremony further highlighted his role in brokering the dispute, as well as ASEAN’s eagerness to secure Trump’s presence at the summit.

For ASEAN, the high-profile event offered a tangible achievement: a cease-fire between two neighbors with a history of border frictions that could be heralded as a success for regional diplomacy. But it should not be conflated with a lasting resolution. Media accounts and eyewitness reporting underscore that the agreement, while welcome, is fragile—it is a political moment more than a durable settlement of long-running disputes. The US role was catalytic, providing diplomatic pressure and visibility, but the hard work of implementation will fall to the parties themselves and the regional mechanisms that will monitor compliance.

Timor-Leste joins ASEAN

The other major headline from this week’s ASEAN summit was a splashy ceremony marking the long-awaited accession of Timor-Leste as ASEAN’s eleventh member. Tiny and democratic Timor-Leste—the region’s youngest nation and one of its poorest economies—has spent more than a decade pursuing membership and enacting the reforms necessary to qualify. The final hurdle was overcoming objections from military-ruled Myanmar, which blocked ASEAN consensus on the grounds that Timor-Leste had violated ASEAN’s principle of noninterference by expressing support for the National Unity Government, the opposition coalition that challenges Myanmar’s junta.

For Timor-Leste, ASEAN membership brings the promise of greater diplomatic weight, expanded market access, and increased development support. It also injects another democratic voice into a regional forum that has at times been divided over issues such as human rights—precisely the factor that prompted Myanmar’s resistance. For ASEAN, admitting Timor-Leste is a natural and overdue step that refreshes its claim to regional representativeness and inclusivity.

Yet ASEAN’s past experience of enlargement has been double-edged. The absorption of Cambodia, Laos, Myanmar, and Vietnam into ASEAN in the 1990s expanded the bloc’s diplomatic and economic weight, but it also tested ASEAN’s internal cohesion—especially amid intensifying US-China rivalry. ASEAN’s ability to help Timor-Leste build institutional capacity for its membership and navigate external pressures will be an early indicator of whether this enlargement will strengthen or strain ASEAN solidarity.

ASEAN’s diplomatic successes and underlying challenges

Taken together, the summit’s headlines—the Trump-brokered Thailand–Cambodia truce and Timor-Leste’s flag-raising—offered useful optics and a reassuring narrative of ASEAN centrality. But the more consequential story is the growing mismatch between ASEAN’s public diplomacy and its outmoded consensus model. ASEAN excels at consensus rituals that convene the region, trumpet unity and dialogue, and produce face-saving outcomes for leaders. These convenings are politically valuable: They preserve dialogue, reaffirm norms of non-coercion, and create low-cost avenues for cooperation. Yet when the issues at stake require coercive leverage or majoritarian consensus over recalcitrant members, ASEAN’s toolkit is thin.

This limitation has become increasingly visible as the region faces more complex crises—from maritime tensions in the South China Sea to the escalating civil war in Myanmar.

The shadow of Myanmar

Another important issue has loomed in the background during this summit. More than four years after Myanmar’s military junta overthrew the civilian government and plunged the country into civil war, the regime has announced plans to hold elections in December in a bid to legitimize its rule. This move flies in the face of ASEAN’s Five-Point Consensus (FPC), which demands, among other things, an end to violence, humanitarian access, and dialogue with opposition political parties.

ASEAN has struggled to find leverage to advance the FPC or meaningfully address the conflict. Myanmar’s junta leaders are barred from attending ASEAN meetings, although Myanmar retains its full membership in the grouping. At the summit in Kuala Lumpur, leaders once again reaffirmed their commitment to the FPC and quietly rejected Myanmar’s request to send an ASEAN team of observers to monitor the December elections. Yet they stopped short of condemning the junta’s decision to hold the polls. The final communiqué expressed “deep concern” and repeated familiar language about the need for dialogue, humanitarian access, and de-escalation—a sign of both ASEAN’s continued engagement and its inability to exert meaningful influence over Myanmar’s political and humanitarian decisions.

The Philippines takes the reigns as ASEAN chair

Next year will serve as a test for ASEAN on several fronts. Progress on Myanmar and a Code of Conduct on the South China Sea remains stalled, the Thailand-Cambodia cease-fire remains fragile, and the process of facilitating Timor-Leste’s integration will require attention. With Malaysia now handing hosting duties to the Philippines—a US ally with active maritime disputes with China—Manila is likely to push the South China Sea to the top of the agenda and press for stronger ASEAN coordination. But it will also be eager to secure Trump’s participation in the East Asia summit, no small feat given his sporadic attendance at regional meetings. If this year serves as a guide, one might expect Manila to try to choreograph a special ceremony for Trump to take center stage.

Amy Searight is a nonresident senior fellow in the Indo-Pacific Security Initiative at the Atlantic Council’s Scowcroft Center for Strategy and Security.

Further reading

Mon, Oct 27, 2025

Trump’s place in history depends on his approach to the CRINK

Inflection Points By Frederick Kempe

After a string of foreign policy wins, Trump's more significant challenge lies ahead: countering the bloc of China, Russia, Iran, and North Korea.

Wed, Oct 15, 2025

What Taiwan can learn from China’s gray-zone actions against the Philippines

Report By Chung-Yu Chou

China uses different tactics for different aims: slow but persistent maritime incursions off the coast of the Philippines and high-speed aerial harassment in Taiwanese airspace. But Manila’s responses offer useful lessons for Taipei. A new study of the Philippines’ experience shows what Taiwan can do to create limits on Chinese action without triggering open conflict.

Thu, Jul 24, 2025

Dispatch from Manila: A lesson in calling out Chinese maritime aggression

New Atlanticist By Markus Garlauskas, Philip W. Yu

As the Philippines has focused more on Chinese threats to itself, Manila also seems increasingly inclined to see its own security as connected to that of the broader region.

Image: Malaysia's Prime Minister Anwar Ibrahim, Thailand's Prime Minister Anutin Charnvirakul and Cambodia’s Prime Minister Hun Manet look on as U.S. President Donald Trump speaks ahead of the signing of a ceasefire deal between Cambodia and Thailand on the sidelines of the 47th Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) summit in Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, October 26, 2025. REUTERS/Evelyn Hockstein