French President Charles de Gaulle in 1963 vetoed the British application to join the European Community (EC)—the precursor of today’s European Union (EU). The British decision to leave the EU in a so-called Brexit referendum would not have surprised the great de Gaulle at all.

After many years of British refusal to consider membership in the European integration effort, de Gaulle accurately perceived the United Kingdom’s 1963 commitment to Europe as still prejudiced by its Commonwealth ties and, most importantly, by its special relationship with the United States. De Gaulle saw the UK as an “Atlanticist” Trojan horse and explained in a 1963 press conference his veto saying that British participation in the EC would undermine European cohesion, and “in the end there would appear a colossal Atlantic Community under American dependence and leadership, which would completely swallow up the European Community. De Gaulle’s worst case scenario never came to pass, even though it has continued to cast a shadow over French attitudes toward Britain’s role in the EU.

In the early 1970s, the UK decided to try again. The political sands in Paris had shifted when de Gaulle resigned from his presidency in 1969 following the defeat of a referendum on government reform, which he had turned into a vote of confidence in his leadership. He was replaced by Georges Pompidou—a more pragmatic Gaullist who had not tied his prestige to the British membership issue. In the meantime, the UK had turned toward Europe as it withdrew its forces that were deployed east of Suez while its trade interests were shifting from the Commonwealth toward the continent.

Many Brits had not yet accepted that the UK was part of Europe, and often talked about “going to Europe” when crossing the Channel. But the combination of a more willing French government and a tentative British acceptance that the UK’s future would require a shift from Commonwealth to Europe ultimately brought the UK into the EC on January 1, 1973.

Against the backdrop of this history, it is not surprising that continental EU members are disinclined to offer the departing UK a sweet deal. It is not just out of spite or in honor of de Gaulle’s skepticism of the UK’s European avocation. The larger concern is that other EU members might follow the British example in the wake of the referendum, leading to a complete unraveling of the integration process. US governments have supported the European integration process since the 1940s, judging that cooperation among the European democracies would help prevent a third world war starting in Europe and would serve as a bulwark against the Soviet Union’s power and ideology. Washington regretted de Gaulle’s block of British membership, feeling that the UK would bring some transatlantic character to the process—confirming in some way exactly what de Gaulle had feared.

While de Gaulle might today feel warranted in his skepticism with regards to the British vote, he might also find himself sympathizing with the nationalist sentiments that have gained ground following the referendum. While de Gaulle questioned the UK’s passion for European integration, his idea of a united Europe did not exactly match some of the motivations that have been driving the EU’s integration process. For de Gaulle, a united Europe should be a Europe des patries—a Europe of states—in which each member retained its fundamental sovereignty. If that were today’s EU, perhaps Brexit would never have caught on.

Whatever de Gaulle might say if he were around today, the British departure is a serious blow to the European project. While it might remove the country arguably most focused on retaining national sovereignty, it also steals the process of economic strengths, strategic perspectives, and military capabilities. Continued British membership in NATO will keep the UK involved in transatlantic defense, and perhaps a variety of bilateral arrangements will allow the UK to participate in some EU defense cooperation projects. But the departure of the UK from the EU will truly re-shape Europe, and perhaps not for the better of either side.

Stanley R. Sloan is a fellow with the Council’s Brent Scowcroft Center of International Security. His new book Defense of the West, NATO, the European Union and the Transatlantic Bargain will be published by the Manchester University Press in September. You can follow him on Twitter at @srs2_.

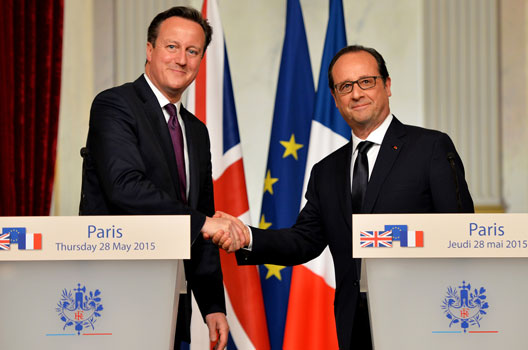

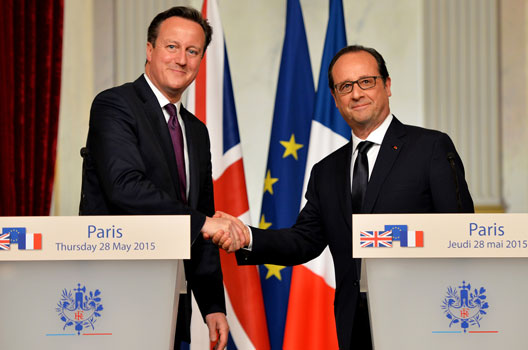

Image: From left: Then-Prime Minister David Cameron meets with French President François Hollande at the Palace of Elysee in Paris on May 27, 2015. (Prime Minister’s Office/Arron Hoare)