Putin’s next move? Five Russian attack scenarios Europe must prepare for

Bottom lines up front

- If Vladimir Putin can’t win a clear victory in Ukraine, he will seek one elsewhere; a clear victory in Ukraine would embolden Moscow to further aggression.

- Europe must prepare to meet these threats with less American support.

- The lowest risk option for Moscow—and therefore most likely—is Russian forces occupying Norway’s Svalbard archipelago.

Table of contents

- The strategic setting: Autocrats on the rise

- The threat: A formidable military backed by a resilient war economy

- The risk: NATO is not ready

- Target 1: Svalbard archipelago

- Target 2: Åland islands

- Target 3: Eastern Estonia

- Target 4: Gotland

- Target 5: Land bridge to Kaliningrad

The accession of Sweden and Finland as NATO’s newest members has fundamentally altered Russia’s security calculations in the Baltic and Nordic region. Should the war in Ukraine evolve into a prolonged frozen conflict, Russia will rearm its military in pursuit of Vladimir Putin’s imperial ambitions. He will seek opportunities to rebuild Russian prestige and recover former or disputed territories, improve Russia’s strategic posture, and test NATO’s resolve in Article 5 scenarios in which he assesses the chance of a robust Alliance response is low, or the chances of success at acceptable cost are high. As one expert notes, “Russia wants to expand its military and political opportunities in the face of the West and considers a direct clash with the West highly probable, if not unavoidable.”1Pavel Luzin, “Russia Reorganizes Military Districts,” Jamestown Foundation, February 29, 2024, https://jamestown.org/program/russia-reorganizes-military-districts.

The potential rewards for continued and successful Russian aggression in Europe include enhanced prestige for Putin’s regime, an improved geostrategic position along Russia’s periphery, delivery of a damaging and perhaps fatal blow to NATO, and the severing of the transatlantic link—all of which are powerful incentives. To deter future Russian aggression, NATO should identify and address these challenges now with concrete solutions. If Putin succeeds in such tests the lack of an effective response could well fracture NATO, fundamentally altering the transatlantic security environment.2These scenarios figure prominently in recent publications such as “If Russia Wins” by noted NATO scholar Carlo Masala and “War with Russia” by former Deputy SACEUR General Sir Richard Shirreff, both best sellers.

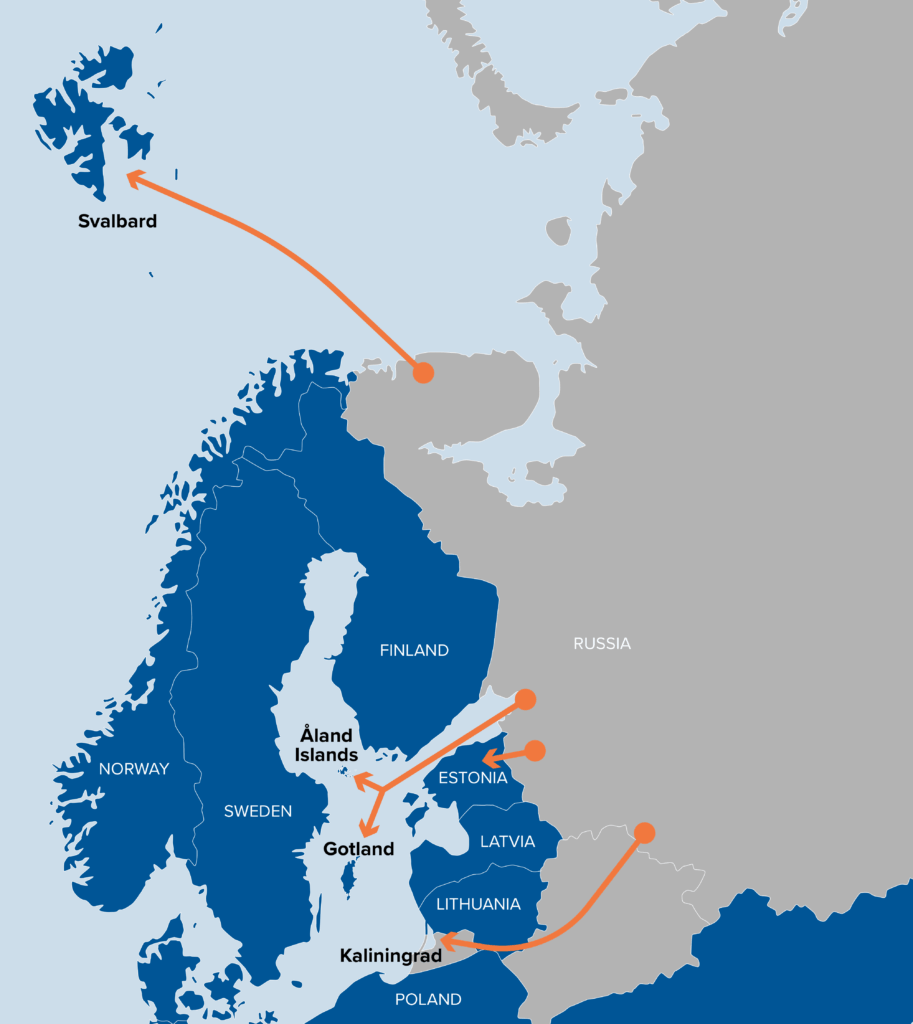

Despite its war in Ukraine, Russia remains a formidable, capable, and determined adversary in possession of the world’s largest and strongest nuclear arsenal. As Western intelligence services have warned, the Russian military is reconstituting its forces in preparation for future contingencies. Senior NATO military and intelligence leaders regularly warn that Russian aggression on NATO territory in the near term is a serious threat.3Tom Dunlop, “Germany Warns Russia May Be Preparing Attack on NATO,” UK Defense Journal, March 29, 2025, https://ukdefencejournal.org.uk/germany-warns-russia-may-be-preparing-attack-on-nato; Anne Kauranen, “Finland’s Intelligence Chief Urges Vigilance over Planned Russian Military Build-up,” Reuters, January 16, 2025, https://www.reuters.com/world/europe/finlands-intelligence-chief-urges-vigilance-over-planned-russian-military-build-2025-01-16/; Aleks Phillips and Paulin Kola, “Sweden Says Russia Is Greatest Threat to Its Security,” BBC, March 11, 2025, https://www.bbc.com/news/articles/c89y8gn2w8vo. This study will assess five key scenarios in which Russia might seek to improve its geostrategic position in the Nordic-Baltic region—the most likely target for future Russian aggression on NATO territory. In order of least to most risk for Russia, these are: military occupation of Svalbard; military occupation of the Åland islands; seizure of NATO territory in eastern Estonia; seizure of Gotland; and military operations to establish a land corridor to Kaliningrad. The intent of the study is to develop specific, realistic, and practical recommendations to deter Russian aggression in the Nordic and Baltic region.

The strategic setting: Autocrats on the rise

In 2025 the transatlantic community finds itself facing multiple serious challenges, framed by major-theater war on its doorstep in Ukraine, a new US administration critical of NATO and strongly prioritizing the homeland and China, dissensus within the Alliance on burden sharing and how to deal with Russia, and the potential for further Russian aggression in the European security space. More broadly, a consortium of autocratic states (China, Russia, Iran, and North Korea)—enabled by supporters such as India, Brazil, South Africa, and others—supports Russian aggression in Ukraine directly and indirectly by providing arms, troops, or markets that prop up Russia’s war economy.4Nicole Bibbins Sedaca, “Russia’s Attack on Ukraine Is Part of a Larger Wave of Authoritarianism,” Bush Center, Spring 2022, https://www.bushcenter.org/catalyst/ukraine/bibbins-sedaca-russia-attack-on-ukraine-part-of-wave-of-authoritarianism.

The strongest and most alarming trend in global affairs is the rise of autocratic regimes that threaten the stability of the international system. On every continent, democratic institutions face concerted opposition from authoritarian movements and regimes seeking to undermine the rule of law, free elections, and constitutional frameworks. Many of these movements are supported and financed by China and Russia. As Europe and the United States struggled to recover from the effects of the pandemic, global supply chain disruptions, and rising inflation, worsening tensions in the Indo-Pacific region and the outbreak of major-theater war in Ukraine roiled international markets, energy transfers, and food supplies. The international system today is marked by instability and increasing fragmentation as traditional alliances and coalitions come under growing pressure and strain.5Joshua Kurlantzick, “The Growing, Broad, Authoritarian Network and Its Ramifications for the World,” Council on Foreign Relations, last visited November 3, 2025, https://www.cfr.org/project/new-global-authoritarianism-china-and-russias-strategic-support-autocracies.

US economic policy, foreign policy, and national security responses to these challenges under the current administration differ strikingly from those of the past. US leaders have strongly condemned European Union (EU) trade practices, harshly criticized NATO member states, and imposed stiff tariffs on European and Canadian goods, provoking angry economic retaliation and damaging diplomatic relationships with traditionally staunch allies.6Koen Verhelst, “EU Wields ‘Sledgehammer’ Against Trump Tariffs,” Politico, March 12, 2025, https://www.politico.eu/article/eu-tariffs-donald-trump-diplomat-eu-war-defending-nation-bloc/. It remains to be seen whether these measures are bargaining chips, which can be lessened or withdrawn in exchange for European concessions (such as increased defense spending or US defense contracts), or long-term shifts in US policy. US conservatives today regularly call for disengagement from Europe.7Ben Friedman, “A New NATO Agenda: Less U.S., Less Dependency,” Defense Priorities, July 8, 2024, https://www.defensepriorities.org/explainers/a-new-nato-agenda/. Apparently serious US threats to expand territory by annexing Canada and Greenland have widened this breach, a process only intensified by the Donald Trump administration’s embrace of far-right movements across Europe and autocratic leaders such as Hungary’s Viktor Orban. Senior officials have repeatedly argued that Europe must “look to itself” for security so that the United States can prioritize the Indo-Pacific, now described as its “sole pacing threat.”8Dan Sabbagh, “US No Longer ‘Primarily Focused’ on Europe’s Security, Ssays Pete Hegseth,” Guardian, February 12, 2025, https://www.theguardian.com/us-news/2025/feb/12/us-no-longer-primarily-focused-on-europes-security-says-pete-hegseth. Increasingly, the United States is no longer seen across Europe as a reliable ally with common values and interests.9“Germany’s likely next chancellor has warned that the United States cares little about Europe’s fate,” as quoted in: Henry Ridgewell, “German Election Winner: Europe Must Defend Itself as US ‘Does Not Care,” Voice of America, February 25, 2025.

Several alternative futures thus appear possible, ranging from outright US withdrawal to a measured drawdown of forces to a purely transactional approach, whereby the United States demands bilateral concessions (more European forces and defense spending, as well as economic and trade concessions) in exchange for continued support.10Giuseppe Spatafora, “The Trump Card: What Could US Abandonment of Europe Look Like?” European Institute for Security Studies, February 17, 2025, https://www.iss.europa.eu/publications/briefs/trump-card-what-could-us-abandonment-europe-look. Regardless of which outcome materializes, it seems clear that Europe must rapidly increase its defense capabilities. For the contingencies addressed in this study, solutions that rely primarily on European contributions are optimal.

The threat: A formidable military backed by a resilient war economy

Russian aggression in Europe clearly presents the most serious challenge facing NATO and the European Union.11This section is adapted from: Richard D. Hooker, Jr., “Building a Stronger Europe,” Harvard Kennedy School’s Belfer Center for Science and International Affairs, February 12, 2025, https://www.belfercenter.org/research-analysis/building-stronger-europe-companion-new-transatlantic-bargain. The 2022 NATO Strategic Concept highlights Russia as “the most significant threat to Allied security,” while the 2025 Hague Summit cites the “long-term threat posed by Russia to Euro-Atlantic security.”12“NATO 2022 Strategic Concept,” NATO, July 18, 2022, https://www.nato.int/cps/en/natohq/topics_56626.htm#:~:text=The%20current%20Strategic%20Concept%20%282022%29%20reaffirms%20that%20NATO%E2%80%99s,defence%2C%20crisis%20prevention%20and%20management%2C%20and%20cooperative%20security; “The Hague Summit Declaration,” NATO, press release, June 25, 2025, https://www.nato.int/cps/en/natohq/official_texts_236705.htm. Following its seizure of Georgian territory in 2008, the occupation of Crimea in 2014, and the incursion into the Donbas in the same year—the latter two both sovereign Ukrainian territory—the Russian Federation conducted a festering campaign in eastern Ukraine resulting in more than fifty thousand killed and wounded through 2021.13“Conflict-Related Civilian Casualties in Ukraine,” United Nations Human Rights Monitoring Mission in Ukraine, January 27, 2022, https://ukraine.un.org/sites/default/files/2022-02/Conflict-related%20civilian%20casualties%20as%20of%2031%20December%202021%20%28rev%2027%20January%202022%29%20corr%20EN_0.pdf. In February 2022, Russia launched an unprovoked, massive invasion of Ukraine that continues today.

Russian losses in Ukraine have been severe, with as many as 770,000 killed, wounded, or missing, more than twice the size of the entire initial invasion force.14Bojan Pancevski, “One Million Are Now Dead or Injured in the Russia-Ukraine War,” Wall Street Journal, September 17, 2024, https://www.wsj.com/world/one-million-are-now-dead-or-injured-in-the-russia-ukraine-war-b09d04e5; Yurri Clavilier and Michael Gjerstad, “Combat Losses and Manpower Challenges Underscore the Importance of ‘Mass’ in Ukraine,”International Institute of Strategic Studies, February 10, 2025, https://www.iiss.org/online-analysis/military-balance/2025/02/combat-losses-and-manpower-challenges-underscore-the-importance-of-mass-in-ukraine/. (A disproportionate number are non-ethnic Russians drawn from more rural areas.15Paul Goble, Mairbek Vatchagaev, and Valeriy Dzutsati, “Nationalities at War: Non-Ethnic Russians in Putin’s War against Ukraine,” Saratoga Foundation, April 25, 2025, https://www.saratoga-foundation.org/p/eurasia-outlook-nationalities-at. ) Most of Russia’s inventory of modern main battle tanks—some three thousand in all—have been destroyed or captured, along with 5,600 armored fighting vehicles, 1,500 artillery systems, 110 fixed-wing aircraft, and more than one hundred helicopters.16Jakub Janovsky, et al., “Attack on Europe: Documenting Russian Equipment Losses During the Russian Invasion of Ukraine,” Oryx, February 24, 2022, https://www.oryxspioenkop.com/2022/02/attack-on-europe-documenting-equipment.html. The Russian Black Sea Fleet has also been crippled, with seventeen ships sunk (including the flagship cruiser Moskva). At the outset, all of Russia’s then eleven combined-arms armies, its one tank army, and all of its airborne/air assault and naval infantry forces were committed to the invasion. That force was shattered by more than two years of intense combat.

Nevertheless, the Russian Federation’s ability to replace its losses has been remarkable.17Andrew A. Michta and Joslyn Brodfuehrer, “NATO-Russia Dynamics: Prospects for Reconstitution of Russian Military Power,” Atlantic Council, September 19, 2024, https://www.atlanticcouncil.org/in-depth-research-reports/report/nato-russia-dynamics-prospects-for-reconstitution-of-russian-military-power/. Through forced conscription and by offering financial incentives to boost recruiting, Russian forces fighting in Ukraine now total more than six hundred thousand.18Murray Brewster, “Ravaged by War, Russia’s Army Is Rebuilding with Surprising Speed,” CBC News, February 23, 2024, https://www.cbc.ca/news/politics/russia-army-ukraine-war-1.7122808. By drawing on reserve stocks of older equipment and ramping up production, Russia has made up for equipment losses, albeit with older and less capable systems and weapons.19Mark Trevelyan and Greg Torode, “Russia Refits Old Tanks after Losing 3,000 in Ukraine—Research Centre,” Reuters, February 13, 2024, https://www.reuters.com/world/europe/russia-relying-old-stocks-after-losing-3000-tanks-ukraine-leading-military-2024-02-13/. At the Munich Security Conference in February 2025, President Volodymyr Zelenskyy reported that Russia is building an additional fifty combat divisions, totaling some 150,000 troops—far more than any European state.20“Ukraine Receives UAH 267B in Western Aid over Three Years of War,” UKRINFORM, February 15, 2025, https://www.ukrinform.net/rubric-economy/3960455-ukraine-receives-uah-267b-in-western-aid-over-three-years-of-war.html; Thomas Grove, “The Russian Military Moves that Have Europe on Edge,” Wall Street Journal, April 27, 2025, https://www.msn.com/en-us/politics/international-relations/the-russian-military-moves-that-have-europe-on-edge/ar-AA1DJhEx. Supported by China, Iran, North Korea, and others, Russia has managed to evade sanctions to obtain the microchips and other advanced electronics it needs to manufacture and repair its advanced military technology.21Camille Gijs, Jakob Hanke Vela, and Nicolas Camut, “Russia Is Getting Better at Evading Western Sanctions on Electronics, US Official Says,” Politico, June 8, 2023, https://www.politico.eu/article/russia-better-evading-western-sanctions-electronics-war-ukraine/. Now on a war footing, with defense spending exceeding 6 percent of gross domestic product (GDP), Russia has escaped the worst effects of international sanctions.22“Russian Federation,” International Monetary Fund, last visited November 3, 2025, https://www.imf.org/en/Countries/RUS. There is little evidence to suggest its economy will collapse in the near or medium term.23“Missiles of Russia,” Center for Strategic and International Studies, last updated August 10, 2021, https://missilethreat.csis.org/country/russia/.

The state of the Russian military

The Russian armed forces consist of 1.5 million active-duty soldiers, with another nine hundred thousand reservists, organized into three branches (the aerospace forces, ground forces, and navy), two independent arms (the strategic rocket forces and airborne forces) and the Special Operations Forces Command. The National Guard and Border Service are paramilitary formations not controlled by the Russian General Staff. Russian military forces are made up of both contract and conscripted soldiers, with elite formations such as special operation, parachute, and naval infantry enjoying a higher proportion of volunteers. All physically qualified Russian males aged 18–27 are subject to one year of military service.

The world’s strongest nuclear power, Russia fields an array of strategic and tactical nuclear systems that provide a wide range of options on the escalatory ladder.24“Missiles of Russia,” Center for Strategic and International Studies, last updated August 10, 2021, https://missilethreat.csis.org/country/russia/. The total number of nuclear warheads of all types is 5,600, including some two thousand tactical weapons (almost ten times the US number).25“Russia’s Nuclear Inventory,” Center for Arms Control and Non-proliferation,” September 2022, https://armscontrolcenter.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/09/Russias-Nuclear-Inventory-091522.pdf. Russian intercontinental ballistic missiles (ICBMs) are controlled by the strategic rocket forces, headquartered in Moscow with an alternate command post in the Ural Mountains. The aerospace forces control a fleet of some sixty-six strategic bombers, though as many as thirteen were damaged or destroyed in recent Ukrainian drone attacks.26Anna Fratsyvir, “Destroyed Russian Bombers Seen in First Satellite Images after Ukrainian Drone Strike,” Kyiv Independent, June 2, 2025, https://kyivindependent.com/first-satellite-images-show-destroyed-russian-bombers-after-ukrainian-drone-strike-on-belaya-air-base/. The Russian navy has eleven ballistic missile submarines equipped with sea-launched ballistic missiles (SLBMs). Russian ground forces include a variety of tactical nuclear systems, such as the Kalibr cruise missile and Iskander ballistic missile, deployed in the missile brigades found at army level. Russia also possesses air- and sea-launched tactical nuclear weapons in its army and navy. This inventory provides Russian leaders with a variety of escalatory options below the strategic threshold that NATO is poorly equipped to answer.

The Russian ground order of battle today consists of fourteen combined arms armies (CAA), roughly equivalent to NATO corps, and one tank army (the 1st Guards Tank Army or 1GTA) with a total of seventeen army divisions.27These are 1GTA, 6 CAA, 20 Guards CAA, 8 Guards CAA, 5 CAA, 49 CAA, 58 CAA, 41 CAA, 2 Guards CAA, 35 CAA, 36 CAA, 29 CAA, 25 CAA, 14 CAA and 18 CAA. Three army corps are identified, though force structure changes are under way (11th, 68th, and 3rd). See: Mason Clark and Karolina Hird, “Russian Regular Ground Forces Order of Battle,” Institute for the Study of War, October 2023, https://www.degruyterbrill.com/document/doi/10.1515/sirius-2024-1015/html?lang=en&srsltid=AfmBOopfNKuElg6WTdhEThbuZ7H1ST6SoMpzII6PEFCW_9aorJwjyOj1; Karolina Hird, “Restructuring and Expansion of the Russian Ground Forces Hindered by Ukraine War Requirements,” Institute for the Study of War,November 12, 2023, https://understandingwar.org/wp-content/uploads/2025/04/Special20Campaign20Assessment20November2012_0.pdf. (Ukrainian sources report that an additional fifteen divisions will be raised in the near term, although independent confirmation is lacking.28Christina Harward, et al., “Russian Offensive Campaign Assessment February 15, 2025,” Institute for the Study of War, February 16, 2025, https://www.understandingwar.org/backgrounder/russian-offensive-campaign-assessment-february-15-2025.) Russian ground forces also include some twenty-six independent motor rifle or tank brigades. (There are also three “army corps,” non-standard groupings with generally fewer units than armies.) Ground forces are geographically assigned to five military districts (Leningrad, Moscow, Eastern, Southern, and Central).29The Western Military District was split into the Leningrad and Moscow Military Districts in 2024. The Russian Northern Fleet and Arctic Joint Strategic Command lost its status as a military district in this reorganization. See: Luzin, “Russia Reorganizes Military Districts.” Russian field armies are less uniform in organization than in Soviet times and can include as many as three divisions plus supporting arms (as in the case of 1GTA) or as few as a single brigade (as with the 29th CAA in Siberia). However, all armies include an artillery brigade, missile brigade, and air defense brigade. Of note, Russian army units are supported by far more tubed and rocket artillery than is found in any NATO ally, including the United States.30Colonel (Ret) Ted Donnelly, et al., “How Russia Fights,” US Army Europe and Africa, March 2025, https://api.army.mil/e2/c/downloads/2025/07/11/f2b1e75e/how-russia-fights-a-compendium-of-troika-observations-on-russia-s-special-military-operations.pdf.

The Russian military also fields strong airborne/air assault forces (considered a separate service), including four divisions and three separate brigades, often used as spearhead forces in conventional roles (a fifth division is reportedly forming).31The 104th Air Assault Division. Hird, “Restructuring and Expansion of the Russian Ground Forces Hindered by Ukraine War Requirements,” 7. Referred to as Vozdushno-desantnye-voyska (VDV), literally “air landing troops,” all are mechanized with greater firepower and mobility than NATO counterparts. Their primary mission is to seize key strategic terrain in support of military operations or campaigns directed by the Russian General Staff.32Lester W. Grau, “The Russian Army Is an Artillery Army with Tanks” in Donnelly, et al., “How Russia Fights,” 33. Russian naval infantry operates under control of the Russian navy in support of the Northern, Baltic, Black Sea, and Pacific fleets; there are five brigades, organized along army lines. Russian special operations forces (SOF) include eight spetsnaz brigades, much smaller units trained and equipped for deep penetration raids against high-value targets. All of these formations have been badly damaged in Ukraine and are reconstituting.33Jon Jackson, “Russia’s Elite Airborne Suffers ‘Exceptionally Heavy Losses,’” Newsweek, December 14, 2023, https://www.newsweek.com/russia-elite-airborne-suffers-exceptionally-heavy-losses-1852673.

Private military companies (PMCs) such as the Wagner Group must also be considered. They have been used extensively in the Middle East, Africa, and, of course, Ukraine, where they sustained heavy losses.34Raphael Parens, “Wagner Group Redefined: Threats and Responses,” Foreign Policy Research Institute, January 30, 2023, https://www.fpri.org/article/2023/01/wagner-group-redefined-threats-and-responses/#:~:text=Bottom%20Line%20*%20Wagner%20Group%20has%20suffered,and%20the%20Kremlin%20are%20focused%20on%20Ukraine. PMCs offer several advantages: a degree of deniability, flexibility in the place and manner of employment, and a lack of accountability or public outcry when they suffer heavy losses. Since the abortive coup of June 2023, Yevgeniy Prigozhin’s Wagner Group has declined in importance and influence while PMCs have been more strictly subordinated to state control.35Karen Philippa Larsen, “The Rise and Fall of the Wagner Group,” Danish Institute for International Studies, January 9, 2025, https://www.diis.dk/en/research/the-rise-and-fall-of-the-wagner-group. With some twenty-seven PMCs officially registered with the Russian Ministry of Defense, Russia has multiple options for employment of mercenaries in clandestine or covert operations in which a measure of deception is considered advisable. Just such a scenario appears in the 2024 Finnish documentary series Konflicti, which describes the introduction of Russian mercenaries on the Hanko Peninsula in an attempt to destabilize the Finnish government.

On the whole, Russian ground forces have underperformed in Ukraine despite massive superiority in artillery, armored vehicles, and airpower. Pre-war training and combined-arms proficiency were shown to be lacking, while command arrangements, battlefield leadership, and logistic planning have all been criticized.36Lasha Tchantouridze, “Why Russia’s Military Reforms Failed in Ukraine,” National Interest, October 15, 2022, https://nationalinterest.org/feature/why-russias-military-reforms-failed-ukraine-205338. Lack of initiative and an inability to fuse intelligence in support of targeting are common problems.37Mykhaylo Zabrodskyi, et al., “Preliminary Lessons in Conventional Warfighting from Russia’s Invasion of Ukraine,” RUSI Journal, February–July 2022, https://www.rusi.org/explore-our-research/publications/special-resources/preliminary-lessons-conventional-warfighting-russias-invasion-ukraine-february-july-2022. Since 2022, many Russian general officers have been killed, wounded, or relieved, disrupting the chain of command.38Lucy Papachristou, “Senior Russian Commanders Killed by Ukraine since Start of the War,” Reuters, July 3, 2025, https://www.reuters.com/world/europe/senior-russian-commanders-killed-by-ukraine-since-start-war-2025-07-03/. Nevertheless, Russian resilience has been impressive and Russian excellence in some areas, such as electronic warfare and use of drones, is impressive.39Michael Kofman, “Assessing Russian Military Adaptation in 2023,” Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, October 2024, 47, https://carnegie-production-assets.s3.amazonaws.com/static/files/Kofman-Russia-final-2.pdf. The Russian Army today is far more combat experienced than any NATO land force, and it continues to learn and adapt. Its resilience and willingness to take high casualties to achieve its objectives make it a dangerous adversary that should not be underestimated in future conflicts.40Mathieu Boulègue, et al., “Assessing Russian Plans for Military Regeneration,” Chatham House, July 9, 2024, https://www.chathamhouse.org/2024/07/assessing-russian-plans-military-regeneration/02-manpower-force-structure-and-command-and.

Traditionally, the Russian navy has operated in support of its land forces and not at great distances from the homeland, except in small numbers. Those trends are likely to continue.41Michael B. Petersen, “Toward an Understanding of Maritime Conflict with Russia” in Andrew Monahan and Richard Connoly, The Sea in Russian Strategy (Manchester UK: Manchester University Press, 2023), 212. Even so, Russian naval power is increasing, with twenty-three new vessels commissioned since 2023.42Andrew Monaghan, “Russia’s Naval Futures: New Horizons 2050,” NATO Defense College, November 2025, https://www.ndc.nato.int/wp-content/uploads/2025/11/2025_outlook_11.pdf. In the transatlantic region, its principal tasks are to contribute to strategic nuclear deterrence with its submarine-launched ballistic missile submarines; to defend the ballistic missile submarine (SSBN) bastions in and around the Kola Peninsula; to threaten the Atlantic sea lanes with its attack submarines; to defend against enemy sea-launched carrier and missile strikes against critical targets ashore; and to support ground operations with its cruise missiles, naval gunfire, and naval infantry. The Russian navy currently lists 283 vessels in its order of battle, though many are aging or are smaller corvettes or coastal patrol craft. A significant number are partially manned, under refit, or otherwise not battle worthy. Principal surface combatants include one carrier (the Kuznetsov, under long-term refit if not cancellation), four cruisers, ten destroyers, and twelve frigates. These are supported by eighty-three corvettes, forty-eight mine warfare vessels, fifty patrol vessels, and seventeen amphibious assault vessels, along with other support craft. The Russian submarine force consists of fifty-eight vessels, including twelve nuclear ballistic missile boats and fourteen nuclear attack subs.43“Russian Navy (2025),” World Directory of Modern Military Warships, 2025, https://www.wdmmw.org/russian-navy.php. While most Russian submarines were commissioned in the 1980s or 1990s, a small number—such as the nuclear-powered guided missile sub Severodvinsk—are modern, powerful, and difficult to detect.44Eric Wertheim, “Russia’s Capable New SSGN,” US Naval Institute Proceedings, May 2020, https://www.usni.org/magazines/proceedings/2020/may/russias-capable-new-ssgn. The bulk of the Russian navy is assigned to the Northern Fleet, based in Severomorsk on the Kola Peninsula. In confined waters, such as the Black Sea or Baltic Sea, the Russian navy has been shown to be vulnerable to land-based anti-ship missiles as well as unmanned surface attacks.45Scott Savitz and William Courtney, “The Black Sea and the Changing Face of Naval Warfare,” RAND, October 31, 2023, https://www.rand.org/pubs/commentary/2023/10/the-black-sea-and-the-changing-face-of-naval-warfare.html. Beyond the range of its land-based anti-ship missiles, the Russian navy is vulnerable to NATO’s maritime forces—but the European allies will find it difficult to cope without the US Navy.46The UK Royal Navy has only sixteen surface combatants (two carriers, six destroyers, and eight frigates) plus five nuclear attack submarines; the Norwegian Navy has four frigates and six diesel/electric submarines optimized for coastal defense. The Finnish navy has no major surface combatants or submarines. For operations north of the GIUK gap, NATO will be hard pressed without the US Navy. “The Military Balance 2025,” International Institute for Strategic Studies, 2025, https://www.iiss.org/publications/the-military-balance/.

The Russian Air Force, on paper at least, is one of the strongest in the world, with some 1,200 fighter aircraft and more than one hundred bombers, supported by an array of command and control (C2), electronic warfare, transport, and intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance (ISR) aircraft.47“Russian Air Force (2025) Aircraft Inventory,” World Directory of Modern Military Aircraft, 2025, https://www.wdmma.org/russian-air-force.php. Russian aerospace forces also include eleven air and missile defense brigades. The Russian Air Force has not performed well in Ukraine despite its overwhelming numbers and despite facing older Ukrainian air defense systems.48Douglas Barrie and Giorgio Di Mizio, “Moscow’s Aerospace Forces: No Air of Superiority,” International Institute for Strategic Studies, February 7, 2024, https://www.iiss.org/online-analysis/military-balance/2024/02/moscows-aerospace-forces-no-air-of-superiority/. With a ten-to-one superiority in fighter aircraft at the outset, Russia failed to achieve air dominance—primarily due to outstanding Ukrainian air defense, but also due to deficiencies in Russian training and airpower employment. More than one hundred fixed-wing Russian combat aircraft have been lost, while many others are aging out prematurely due to heavy strain in flying hours.49Maya Carlin, “The Russian Air Force Has Suffered Heavy Losses in Ukraine,” National Interest, April 28, 2025, https://nationalinterest.org/blog/buzz/the-russian-air-force-has-suffered-heavy-losses-in-ukraine. About half of Russia’s aircraft fleet is more than thirty years old.50Michael Bohnert, “The Russian Air Force Is Hollowing Itself Out. Air Defenses for Ukraine Would Speed that Up,” RAND, March 29, 2024, https://www.rand.org/pubs/commentary/2024/03/the-russian-air-force-is-hollowing-itself-out-air-defenses.html. Attack and transport helicopters belong to the Russian air force, not the army, and they have also suffered grave losses, losing 40 percent of their strength in combat. Maintenance issues, battle damage, and the requirements of other theaters also reduce the number of airframes available. Effective Ukrainian air defense forced Russia to change tactics, increasing reliance on attack drones and on aerial delivery of glide bombs launched beyond the range of enemy air defenses.51David A. Deptula, “Air Superiority and Russia’s War on Ukraine,” Air and Space Forces, July 26, 2024, https://www.airandspaceforces.com/article/air-superiority-and-russias-war-on-ukraine. Russian high and medium air defense also resides in the air force and is impressive, especially in the air defense bastions surrounding Kaliningrad, St. Petersburg, and the Kola Peninsula. In the near term, Russia will field more modern replacement aircraft in modest numbers, but NATO airpower should have the advantage.52By 2034, European allies are projected to have more than six hundred fifth-generation F-35s. European allies currently field slightly more than two thousand fighter aircraft (F-16, F/A-18, Gripen, Eurofighter, Rafale, and some others). Audrey Decker, “F-35 Sales Rise as Russian Invasion Grinds on,” Defense One, March 23, 2023, https://www.defenseone.com/threats/2023/03/f-35-sales-rise-russian-invasion-grinds/384360/; “Fleet Size,” EUROCONTROL, October 1, 2025, https://ansperformance.eu/economics/cba/standard-inputs/chapters/fleet_size.html. In all scenarios involving military force, Russian unmanned aerial vehicles can be employed en masse and in sophisticated ways, with heavy use of decoys and deliberate targeting of civilian populations and infrastructure if deemed necessary.

Russian politics presents no threat to Putin’s control

Now in power for a quarter of a century, Putin at seventy-two is in firm control of the Russian political system, which stages periodic “show elections” that do not threaten his hold on power. Powerful oligarchs, military and intelligence figures, and legislators cannot establish independent centers of power able to challenge his authority, while opposition figures are regularly imprisoned, assassinated, or executed. As Freedom House reports:

Power in Russia’s authoritarian political system is concentrated in the hands

of President Vladimir Putin. With loyalist security forces, a subservient judiciary, a controlled media environment, and a legislature consisting of a ruling party and pliable opposition factions, the Kremlin manipulates elections and suppresses genuine dissent.53“Russia,” Freedom House, last visited November 3, 2025, https://freedomhouse.org/country/russia.

Strongly nationalist and supported by the Russian Orthodox Church, the Russian political system follows centuries of Russian history as an authoritarian and autocratic regime preoccupied with expansion and external threats. As one expert observes, “The main aim of the system is the perpetuation of the ruling elite’s hold on power, first by shielding it against any challenges that might emerge from the society, and second, by regulating the intra-elite rivalries . . . the state is treated by the elite as if it were its collective property through neo-patrimonialism. Neither citizens’ welfare nor economic development are among its primary goals.”54Witold Rodkiewicz, “Russia’s Political and Social Landscape in the Context of Geopolitical Risks,” Salzburg Global, December 18, 2023, https://www.salzburgglobal.org/news/topics/article/russias-political-and-social-landscape-in-the-context-of-geopolitical-risks. The Russian system is opaque, rendering independent assessments and analyses difficult. Catastrophic defeat on the battlefield, economic collapse, or serious internal rivalries might conceivably cause Putin’s overthrow, but at present his hold on power appears solid and durable. For planning purposes, analysts should assume that the current power structures will remain in place through Putin’s lifetime.

The Russian economy has rebounded from sanctions pressure

Though beset with comprehensive sanctions since 2022, the Russian economy has proven to be resilient, with GDP growing by 3.4 percent in 2024 as Russia transitioned to a war economy. There is disagreement regarding Russian economic prospects going forward.55Simon Saradzhyan, “Is Russia’s Economy Collapsing,” Russia Matters, February 6, 2025, https://www.russiamatters.org/blog/russias-economy-collapsing. Rising inflation and interest rates, corporate debt increases, a weakening ruble, declining energy prices, labor shortages, sharp reductions in foreign investment, and the loss of European markets for Russian energy have all negatively impacted Russian economic performance.56Brendan Cole, “Russian Ruble Collapses as Putin’s Economy in Trouble,” Newsweek, November 27, 2024, https://www.newsweek.com/russia-ruble-dollar-currency-economy-1992332. Diversion of capital into the defense sector has also affected investment in other parts of the economy, stunting efforts to offset these impacts.57Mark Temnycky, “Is 2025 the Year that Russia’s Economy Finally Freezes Up Under Sanctions?” Atlantic Council, January 8, 2025, https://www.atlanticcouncil.org/blogs/new-atlanticist/is-2025-the-year-that-russias-economy-finally-freezes-up-under-sanctions. Russia’s sovereign wealth fund has also declined from $175 billion in early February 2022 to $135 billion in March 2025, while $340 billion in Russian assets held in foreign banks were frozen following the 2022 invasion of Ukraine.58Elena Fabrichnaya and Guy Faulconbridge, “What and Where Are Russia’s $300 Billion in Reserves Frozen in the West?” Reuters, December 28, 2023, https://www.reuters.com/world/europe/what-where-are-russias-300-billion-reserves-frozen-west-2023-12-28/. Some economists therefore conclude that the Russian economy might collapse or decline in the near term.59Oleksiy Hrushevsky, “The Collapse of the Russian Economy Is Near—Wage Arrears Have Tripled,” Online.UA, December 26, 2025, https://news.online.ua/en/the-collapse-of-the-russian-economy-is-near-wage-arrears-have-tripled-899906/.

Others, however, point to factors that challenge this assessment.60“An unbiased assessment of Russia’s economic capabilities . . .… excludes almost any chances of a serious crisis caused by internal factors in at least three to five-years.” Ben Aris, “Russia’s Economy Is Tougher than It Looks, No Chance of a Crisis in the Next 3–5 Years,” BNE Intellinews, November 14, 2024, https://www.intellinews.com/russia-s-economy-is-tougher-than-it-looks-no-chance-of-a-crisis-in-the-next-3-5-years-case-353210. Russia is self-sufficient in both agriculture and energy, rendering the state at least partially immune to external economic pressures. It includes perhaps the world’s largest reserves of natural resources, including oil, natural gas, timber, iron ore, coal, bauxite, diamonds, rare earths, and other commodities. The Russian shadow fleet, chartered by Russian entities but operating under foreign registries, includes hundreds of vessels engaged in carrying Russian cargoes (principally oil and natural gas) in order to evade international sanctions.61Erik Brown, “The Baltic Sea at a Boil: Connecting the Shadow Fleet and Episodes of Subsea Infrastructure Sabotage,” Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, June 5, 2025, https://carnegieendowment.org/research/2025/06/baltic-russia-maritime-cable-sabotage/?lang=en. The Russian steel industry ranked first in Europe in 2024 with $74 billion in revenue.62“A Guide to Russia’s Resources,” Geohistory, January 8, 2025, https://geohistory.today/resource-extraction-export-russia/.

With new energy markets in China, India, Turkey, and elsewhere, the Russian energy sector has adapted well to Europe’s attempts to wean itself from Russian oil and natural gas (though a substantial fraction of Europe’s energy today is still supplied by Russian energy purchased from other countries on the secondary market and transported by Russia’s shadow fleet to avoid sanctions).63“EU Imports of Russian Fossil Fuels in Third Year of Invasion Surpass Financial Aid Sent to Ukraine,” Centre for Research of Energy and Clean Air, April 10, 2025, https://energyandcleanair.org/publication/eu-imports-of-russian-fossil-fuels-in-third-year-of-invasion-surpass-financial-aid-sent-to-ukraine/. The EU also continues to import Russian oil, nickel, natural gas, fertilizer, iron, and steel.64“US and Europe Do Billions in Trade with Russia Despite Sanctions,” Reuters, September 15, 2025, https://www.reuters.com/business/autos-transportation/us-and-europe-do-billions-trade-with-russia-despite-sanctions-2025-09-15/. Wages for Russian workers across the economy have risen and are running well ahead of inflation, while sanctions regimes have historically eroded as international business interests push for renewed access to Russian markets, commodities, and capital. Trade with China alone has risen by 70 percent, or $237 billion, since 2021.65“Russian Wage Growth Hits 16-Year Peak Amid Race to Find Workers,” Bloomberg, March 5, 2025, https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2025-03-05/russian-wage-growth-hits-16-year-peak-amid-race-to-find-workers. Since then, Russia has transformed its economy to sharply prioritize military production, a change that will not be reversed quickly.66Philip Luck, “How Sanctions Have Shaped Russia’s Future,” Center for Strategic and International Studies, February 24, 2025, https://www.csis.org/analysis/how-sanctions-have-reshaped-russias-future. Russian debt, by international standards, is relatively moderate at 20 percent of GDP.67Heli Simola, “Falling Oil Prices Reduce Russia’s Budget Revenues,” Bank of Finland, May 5, 2025, https://www.bofbulletin.fi/en/blogs/2025/falling-oil-prices-reduce-russia-s-budget-revenues/. Unlike European consumers, the Russian population—especially in a starkly autocratic Russian state—appears well able to withstand privation and hardship. Given these realities, Russia is unlikely to suspend its military ambitions anytime soon due to economic constraints.68“Russia’s economy has confounded expectations throughout the war and, despite suffering several complications, remains well-placed to support the Kremlin’s ambitions in Ukraine and beyond.” Richard Connolly, “Russia’s Wartime Economy Isn’t as Weak as It Looks,” Royal United Services Institute for Defence and Security Studies, January 22, 2025, https://www.rusi.org/explore-our-research/publications/commentary/russias-wartime-economy-isnt-weak-it-looks. Stronger Western sanctions could change this calculus, but sanctions fatigue and an erosion of the sanctions regime over time appear just as likely.69Aaron Krolik, “Lack of New U.S. Sanctions Allows Restricted Goods and Funds into Russia,” New York Times, July 2, 2025, https://www.nytimes.com/2025/07/02/us/politics/trump-russia-sanctions.html. While long-term collapse is possible, Russia seems well able to sustain its military activity for the near to medium term.

Russian hybrid operations seek to “fracture” Europe

Russian capabilities in the information domain are formidable and include offensive cyber, subversion, propaganda, and disinformation. State-sponsored media such as RT and Sputnik collaborate with sophisticated hacking and social media manipulation to sow dissension and distrust of institutions on a global scale. Financial support for opposition parties in Western democracies is a favored tactic with proven results; the recent election of an almost unknown, Russian-backed candidate in the Romanian presidential election is a primary example.70The election result was subsequently annulled by Romania’s constitutional court. Tim Ross and Andrei Popoviciu, “How Putin Won the Romanian Election,” Politico, December 23, 2024, https://www.politico.eu/article/how-vladimir-putin-win-romania-election-calin-georgescu/. (As another example, almost every living Austrian chancellor has accepted highly paid employment with Russian businesses upon leaving office.71Matthew Karnitschnig, “How Austria Became Putin’s Alpine Fortress,” Politico, June 5, 2023, https://www.politico.eu/article/austria-russia-vladimir-putin-alpine-fortress-ukraine.) Russian interference in US elections in 2016, 2020, and 2024 is well documented.72Lily Hay Newman and Tess Owen, “Russia Is Going All Out on Election Day Interference,” Wired, November 5, 2024, https://www.wired.com/story/russia-election-disinformation-2024-election-day/. The Baltic region is a high priority for Russian information operations, which seek to destabilize host nation governments using highly sophisticated means, often leveraging the ethnic Russian populations found there.73Minna Ålander and Patrik Oksanen, eds., “Tracking the Russian Hybrid Warfare,” Stockholm Free World Forum, last visited November 3, 2025, https://frivarld.se/wp-content/uploads/2024/05/Hybrid-Tracker-SFWF.pdf.

Direct sabotage is a regular feature of these efforts. Attacks on Baltic and Nordic infrastructure on land and at sea escalated alarmingly since 2022, often involving explosives and incendiaries as well as targeted assassinations.74Seth G. Jones, “Russia’s Shadow War against the West,” Center for Strategic and International Studies, March 18, 2025, https://www.csis.org/analysis/russias-shadow-war-against-west; Charlie Edwards and Nate Seidenstein, “The Scale of Russian Sabotage Operations against Europe’s Critical Infrastructure,” International Institute for Strategic Studies, August 19, 2025, https://www.iiss.org/research-paper/2025/08/the-scale-of-russian–sabotage-operations–against-europes-critical–infrastructure/. Deniable attacks on undersea infrastructure have increased dramatically and are now a standard part of Russia’s hybrid toolkit.75Benjamin L. Schmitt, Michal Kurtyka, and Alan Riley, “Underwater Mayhem: Countering Threats to Energy and Critical Infrastructure Across the NATO Alliance and Beyond,” University of Pennsylvania, May 2025, https://upenn.app.box.com/s/wvrobfk9j1h34agng36chj73ibtkcx0h. Airspace violations by Russian aircraft and drones are now almost common, most spectacularly on September 9, 2025, when nineteen Russian drones entered Polish airspace.76Tom Balmforth, “Ukraine Says Russia Drone Incursion Part of Pressure Plan against West,” Reuters, September 26, 2025, https://www.reuters.com/business/aerospace-defense/ukraine-says-russia-drone-incursion-part-pressure-plan-against-west-2025-09-26/; Fintan Hogan, “How ‘State-Sponsored’ Drone Activity Is Pushing NATO to Brink,” Times, October 16, 2025, https://archive.is/2025.10.16-111444/https:/www.thetimes.com/world/europe/article/nato-russia-drone-attacks-europe-hfcqnksrb. These activities suggest at least an attempt to probe and test host country and NATO detection and response capabilities, if not a deliberate program of intimidation. Any kinetic operation launched by Russia in the region will almost certainly be preceded by comprehensive hybrid activities meant to fracture civilian support for the authorities, cripple financial and command-and-control systems, and alarm and distract civil society. These efforts are ongoing and increasing on a large scale.77Jones, “Russia’s Shadow War against the West.” As one example, Russia recently “neutralized” the GPS signal to Ursula von der Leyen’s airplane as it was attempting to land in Bulgaria, forcing its pilots to utilize paper maps in order to set down safely. Maia Davies and Will Vernon, “EU Chief von der Leyen’s Plane Hit by Suspected Russian GPS Jamming,” BBC, September 1, 2025, https://www.bbc.com/news/articles/c9d07z1439zo.

Russian objectives

Russian active measures, in the Nordic and Baltic region and more broadly, are based on a series of strategic objectives with deep roots. Among these are:

- enhancing the prestige and stability of the regime by demonstrating influence and power relative to adversaries;

- destabilizing neighboring democratic states;

- laying the groundwork for recovery of former imperial possessions;

- restoration of the Russian Federation as a great power;

- reconfiguration of the international order in ways that benefit Russia in particular, and friendly autocratic regimes in general;

- resetting geostrategic conditions in ways that favor Russian political and military interests and goals;

- conducting intelligence preparation in support of future military operations;

- punishing formerly neutral Sweden and Finland for joining NATO; and

- fracturing the NATO Alliance and the European Union.

Though it has sustained serious losses in Ukraine, Russia remains a capable and determined adversary and the world’s strongest nuclear power. Its ultimate victory in Ukraine is in some doubt, with the conflict likely to subside into yet another frozen conflict.78In this scenario, the conflict subsides into an uneasy stasis along the current line of contact, although fighting can still occur. John Lough, “Four Scenarios for the End of the War in Ukraine,” Chatham House, October 16, 2024, https://www.chathamhouse.org/2024/10/four-scenarios-end-war-ukraine. (In the unlikely event of a Russian victory or a durable peace in Ukraine, Russia is even more likely to consider aggression in other parts of Europe, as more of its forces would be freed for other contingencies.) As Putin has repeatedly asserted, his ambitions go beyond Ukraine and encompass the recovery of former imperial territories lost over the centuries.79Fiona Hill and Angela Stent, “The World Putin Wants,” Foreign Affairs, August 25, 2022, https://www.foreignaffairs.com/russian-federation/world-putin-wants-fiona-hill-angela-stent. Both Finland and Sweden have difficult conflict histories with Russia extending back to imperial times, complicated by Russian anger over their recent accession to NATO.80Anne Kauranen and Johan Ahlander, “A Brief History of Finland’s and Sweden’s Strained Ties with Russia,” Reuters, May 11, 2022, https://www.reuters.com/world/europe/brief-history-finlands-swedens-strained-ties-with-russia-2022-05-12/ Norway, formerly part of Sweden and sharing a border with Russia, is similarly a target of Russian ire as a strong supporter of Ukraine and an outspoken champion of sanctions. Baltic allies Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania are regular targets as well; all formerly belonged to the Russian Empire and all possess ethnic Russian minorities that are oppressed, according to Russian propaganda.81Vladimir Soldatkin, “Putin Derides ‘Russophobia’ in Europe at World War Two Memorial,” Reuters, January 27, 2024, https://www.reuters.com/world/europe/russias-putin-derides-russophobia-europe-world-war-two-memorial-2024-01-27/. They also represent prosperous Western democracies whose high standards of living and free societies stand in sharp contrast to conditions in bordering Russia—a clear threat Putin is known to fear. Standing between Russian territory and the Russian exclave at Kaliningrad (home to the Russian Baltic Fleet), the Baltic states are a high priority for Russian disinformation and subversion, as well as outright aggression.

The Russian Federation today is an aggressive state determined to restore its former glory and its place as a great power.82Daria Dmytriieva, “Putin Is Ready for Small Military Operation against NATO—Polish Counterintelligence,” RBC-Ukraine, May 7, 2024, https://newsukraine.rbc.ua/news/putin-is-ready-for-small-military-operation-1715084131.html. Russian troops occupy Moldovan and Georgian sovereign territory and are based in Armenia as well. With a powerful conventional military and the world’s largest nuclear arsenal, Russia has used force repeatedly and successfully in recent years to achieve its political aims. Western intelligence agencies assess that further aggression is under serious consideration.83“Russia Is Preparing for War with the West—Head of German Intelligence,” Baltic Times, November 28, 2024, https://www.baltictimes.com/russia_is_preparing_for_war_with_the_west_-_head_of_german_intelligence/. Over the next two to five years, Russia will continue to rearm and reconstitute its forces, posing a serious threat to the transatlantic region.84Paul Taylor, “The Threat from Russia Is Not Going Away. Europe Has to Get Serious about Its Own Defence,” Guardian, July 10, 2023, https://www.theguardian.com/world/commentisfree/2023/jul/10/russia-threat-europe-defence-military. Meanwhile, Russian hybrid warfare will continue to play a prominent role.85Souad Mekhennet, et al., “Russia Recruits Sympathizers Online for Sabotage in Europe, Officials Say,” Washington Post, July 10, 2024, https://www.washingtonpost.com/world/2024/07/10/russia-sabotage-europe-ukraine/.

The potential rewards for continued and successful Russian aggression in Europe include enhanced prestige for Putin’s regime, an improved geostrategic position along Russia’s periphery, delivery of a damaging and perhaps fatal blow to NATO, and the severing of the transatlantic link. These are powerful incentives. The most likely scenarios for future Russian aggression in Europe share several factors in common: they are relatively close to Russian territory; they represent a lower probability of a strong NATO or US-led response; they are opposed by weak defending forces; and they are subject to Russian historical claims. Western leaders should have no illusions. The prospects for direct conflict with Russia are substantial.86“Russia wants to expand its military and political opportunities and considers a direct clash with the West highly likely, if not unavoidable, in the near future.” See: Luzin, “Russia Reorganizes Military Districts.” As one senior Nordic officer opined when interviewed for this study, “What Putin says he will do, he does.”

The risk: NATO is not ready

For some seven decades, NATO has been the backbone of North American and European security. The Russian invasion of Ukraine has fundamentally altered the security landscape in which NATO is operating, posing a threat not seen since its inception. How the Alliance meets these challenges will define its future and survival.

Inside the Alliance, NATO faces serious challenges. The Trump administration’s aversion to NATO is well documented, as is its strong prioritization of China as the principal threat.87Ivo H. Daalder, “NATO Without America: How Europe Can Run an Alliance Designed for U.S. Control,” Foreign Affairs, March 28, 2025, https://www.foreignaffairs.com/united-states/nato-without-america. Redeployment of some or all US forces in Europe is reportedly under active consideration.88Connor Stringer, “Trump Considers Pulling Troops oOut of Germany,” Telegraph, March 7, 2025, https://www.telegraph.co.uk/us/politics/2025/03/07/donald-trump-considers-pulling-troops-out-of-germany/; Ellen Mitchell, “Lawmakers Worry US Will Give Up Military Command of NATO,” Hill, March 20, 2025, https://thehill.com/newsletters/defense-national-security/5206676-lawmakers-worry-us-will-give-up-military-command-of-nato/. A steady drift away from NATO’s core values of democracy, human rights, and rule of law in some member states impairs Alliance cohesion.89Interview with former US Ambassador to NATO Doug Lute, July 10, 2025. Key allies such as Canada, Spain, Portugal, Italy, and Belgium still fall well below the defense spending threshold of 2 percent of GDP. Autocratic states such as Hungary, Turkey, and Slovakia refused to participate in sanctions against Russia over Ukraine and represent difficult allies should direct conflict with the Russian Federation erupt. Readiness is low across the Alliance, with half of NATO allies possessing no tanks or combat aircraft. Differing threat perceptions across NATO and the EU further complicate concerted action.

These dynamics suggest opportunities for Russia to exploit in the next few years. The United Kingdom’s difficult exit from the European Union, chronically low interoperability and military readiness across the Alliance, underinvestment in key capabilities such as space, theater missile defense, and offensive cyber, and wide divergences in burden sharing all complicate Alliance cohesion.90Sabine Siebold, “‘50% Battle-Ready’: Germany Misses Military Targets Despite Scholz’s Overhaul,” Reuters, February 13, 2025, https://www.reuters.com/world/europe/50-battle-ready-germany-misses-military-targets-despite-scholzs-overhaul-2025-02-13/. The German government report cited critical deficiencies in virtually all major combat systems. “While the US President’s remarks may have caused some confusion with regard to his commitment to the Atlantic Alliance, the interest of an EU strategic autonomy has appeared much more clearly than before to many of our European partners. We have always been convinced of it; others are much more so today than they were yesterday.” European Affairs Minister Nathalie Loiseau, French Ministry of European and Foreign Affairs, cited in Hajnalke Vincze, “Beyond Macron’s Subversive NATO Comments: France’s Growing Unease with the Alliance,” Foreign Policy Research Institute, November 26, 2019, https://www.fpri.org/article/2019/11/beyond-macrons-subversive-nato-comments-frances-growing-unease-with-the-alliance/. The rise of far-right political movements in Germany, France, and elsewhere raises elemental concerns. Financial and military support for Ukraine is taxing strained defense budgets, particularly given reductions in US aid. Looming over all of this is the question of the US role in NATO going forward. Faced with US demands to raise defense spending to 5 percent of GDP “or else,” a requirement that many allies cannot realistically meet, European states must question the US administration’s actual commitment to the Washington Treaty and the defense of the transatlantic community.91“Likely Next German Chancellor Merz Questions NATO’s Future in ‘Current Form,’” Reuters, February 24, 2025, https://www.reuters.com/world/europe/germanys-merz-questions-longevity-natos-current-form-2025-02-23/; John Deni, “Europeans Are Concerned that the US Will Withdraw Support from NATO. They Are Right to Worry—Americans Should, Too,” Conversation, May 27, 2025, https://theconversation.com/europeans-are-concerned-that-the-us-will-withdraw-support-from-nato-they-are-right-to-worry-americans-should-too-253907. Alarmingly, the head of the German Federal Intelligence Service reported in 2025 that his agency “had clear intelligence indications that Russian officials believed the collective defence obligations enshrined in the NATO treaty no longer had practical force.”92Thomas Escritt, “Russia Could Send ‘Little Green Men’ to Test NATO’s Resolve, German Intelligence Chief Warns,” Reuters, June 9, 2025, https://www.reuters.com/world/russia-has-plans-test-natos-resolve-german-intelligence-chief-warns-2025-06-09/.

NATO’s security posture on its eastern flank is generally characterized by small regular forces, limited reserves, an absence of large armored formations, and weak artillery. The Baltic states presently field no tanks or combat aircraft and only coastal patrol craft. Poland, much larger than its neighbors to the north, is an exception. It has much stronger active and reserve forces and formidable tank, artillery, and fighter holdings (though these are still far smaller than Russian forces). NATO forward forces in the form of multinational battalion battlegroups are present in each of the eastern flank countries.93R. D. Hooker, Jr. and Max Molot, “Building a Stronger Europe: A Companion to the Belfer Center Task Force Report on a New Transatlantic Bargain,” Havard Kennedy School Belfer Center for Science and International Affairs, February 2025, 21–22, https://www.belfercenter.org/sites/default/files/2025-02/Belfer_Building%20a%20Stronger%20Europe_Companion%20Report_1.2.pdf. Lacking strategic depth, the Baltic states are unlikely to successfully defend against Russian aggression without substantial augmentation from allies.

NATO’s posture in Nordic Europe is, in some ways, more reassuring. All Nordic allies (except Iceland, which has no military) require mandatory military service. Defense spending is well above the NATO average and rising. A shared strategic culture, common history, and geographical proximity ensure higher interoperability. Difficult terrain, limited road and rail nets, greater strategic depth, and harsh weather conditions favor the defense. Nordic defense cooperation is long-standing and advanced.94Minna Ålander, “NATO’s New Northern Flank—Don’t Ruin It,” Center for European Policy Analysis, July 20, 2023, “https://cepa.org/article/natos-new-northern-flank-dont-ruin-it/. Finland, Sweden, and Norway, with their long experience bordering Russia, can boast resilient societies marked by high levels of defense preparedness, advanced technology, and significant defense industries. Finland possesses large reserves and the largest artillery inventory in European NATO, while Nordic air forces field some 250 modern fourth- and fifth-generation fighter aircraft.95Karsten Friis, “Reviving Nordic Security and Defense Cooperation,” Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, October 2, 2024, https://carnegieendowment.org/research/2024/10/nordic-baltic-defense-cooperation-nato?lang=en. Nevertheless, minimal force projection capabilities, small active forces, modest ballistic missile defense, and limited blue-water naval strength all constitute vulnerabilities. All Nordic countries lack corps and higher-level formations and staffs with appropriate enablers. A serious threat from Russia would require assistance from across the Alliance.

This discussion feeds into the larger question of how best to deter further Russian aggression in the Nordic-Baltic region under present circumstances. The following considerations should be addressed as the Alliance seeks to meet its many challenges in this dangerous time.

- A shared consensus and commitment to action with respect to Russia is imperative. NATO should establish clear redlines respecting the sovereignty and territorial integrity of members and speak with one voice. A major part of this effort must be combating Russian disinformation through unified and coordinated messaging from capitals.

- Readiness and interoperability are by far the most urgent concerns. Though NATO force structure far outmatches Russia’s on paper, low readiness undermines deterrence across the board.96Germany, France, and the UK cannot field so much as a single division in the Baltic or Black Sea region in less than 90–120 days. See: R. D. Hooker, Jr., “Major Theatre War: Russia Attacks the Baltic States,” RUSI Journal, March 25, 2021, https://www.rusi.org/explore-our-research/publications/rusi-journal/major-theatre-war-russia-attacks-baltic-states. Operational readiness rates, deployment timelines, training, and stocks of ammunition, spare parts, fuel, and precision-guided munitions must all be strengthened and improved.97“Introduction: How Ready?” International Institute for Strategic Studies, November 8, 2024, https://www.iiss.org/publications/strategic-dossiers/introduction-how-ready. Addressing the lack of space-based ISR is an urgent priority.

- Addressing capability shortfalls is also an urgent need. High-altitude air and missile defense, intra-theater airlift, division- and corps-level “enablers,” electronic warfare, and offensive cyber, drone, and counter-drone systems all require investment and strengthening.

- Across Europe, the defense industrial base must grow in size and capacity to generate adequate stocks of major end items (tanks, aircraft, warships), as well as ammunition and spare parts.

- Military mobility, long recognized as a debilitating problem, must be solved. Here, close coordination and effective interaction with the European Union will be required.98Curtis M. Scaparrotti and Colleen B. Bell, “Moving Out: A Comprehensive Assessment of European Military Mobility,” Atlantic Council, April 22, 2020, https://www.atlanticcouncil.org/in-depth-research-reports/report/moving-out-a-comprehensive-assessment-of-european-military-mobility/. Stress testing through regular exercises should be implemented.

- Burden sharing—currently the most divisive issue within the Alliance—must be addressed and rationalized. Overall, NATO allies reached the target of 2 percent of GDP set at the 2014 Summit in 2024, spending $500 billion on defense, or about four times more than Russia. However, key allies such as Italy, Spain, Canada, and Belgium (among others) remain below the 2-percent threshold. To relieve rising pressures related to burden sharing, all allies must achieve a minimum threshold of 2 percent of GDP for defense spending now and show clear progress toward a revised goal of 3.5 percent within the next decade, as agreed at the 2025 NATO Summit at the Hague.

- Updates to NATO’s cyber and nuclear policies are also needed.99Offensive cyber is so highly classified that accurate capability assessments from open sources are lacking. US Cyber Command, the UK’s National Cyber Force, and France’s Directorate General for External Security exercise responsibility for offensive cyber operations, subject to national direction. Other NATO allies might have more limited capabilities. Especially for tactical nuclear weapons, important questions about basing, release authority, site security, deterrent posture, and messaging are all appropriate policy issues affecting NATO as a whole.100Belgium, Germany, Italy, the Netherlands, and Turkey currently host tactical nuclear weapons and possess aircraft and crews able to deliver them. Opposition parties regularly attack these arrangements. See: Constanze Stelzenmuller, “Nuclear Weapons Debate in Germany Touches Raw NATO Nerve,” Brookings, November 19, 2021, https://www.brookings.edu/articles/nuclear-weapons-debate-in-germany-touches-a-raw-nato-nerve/. In the cyber domain, NATO can help to improve cyber defense and cyber awareness across the Alliance, sharing best practices and advanced technology.

- As the conflict in Ukraine has highlighted, addressing the lack of reserves is essential. Small volunteer militaries or limited conscription with short terms of service cannot generate the forces and replacements needed to deter and defend. Conscription based on the Israeli model, especially for those states under greatest threat, will almost certainly be required—and would send a strong deterrent signal.

- Above all, deterrence—the concrete ability and will to inflict unacceptable costs on any aggressor—must be strengthened. This requires the stationing of heavy NATO forces, with enablers, on the eastern flank. Specifically, the enhanced Forward Presence (eFP) battle groups should be increased from battalion to brigade size, as NATO committed to in Madrid in 2022; NATO should assist the Baltic states in transitioning to heavy forces of divisional strength, with enablers; and the US “heel-to-toe” rotational brigade in Poland should be maintained. These forces represent a credible defensive deterrent but are far too small to pose an offensive threat.

Here NATO has many advantages. Its combined GDP is some twenty times greater than Russia’s, and its overall defense spending is some fourteen times greater. NATO’s thirty-two allies and close, official partners such as Japan, Australia, and South Korea constitute most of the economic and military power on the planet, and their combined populations dwarf Russia’s. Nevertheless, NATO must generate the political will to compete. The unity and cohesion of the Alliance is at stake. It is decisively in the US national interest to combine and cooperate with likeminded and wealthy allies who share common values and interests. Accordingly, key Alliance objectives include:

- maintaining Alliance unity and cohesion;

- deterring and defending member states’ sovereignty and territorial integrity;

- increasing overall defense spending;

- correcting capability shortfalls;

- strengthening the defense industrial base;

- improving readiness and interoperability to meet wartime requirements;

- generating manpower reserves; and

- improving NATO-EU cooperation.

What NATO could look like—from the status quo to full US withdrawal

In the near and medium term, NATO might assume one of three forms. The first is the status quo, perhaps with a reduced US footprint and a more transactional approach. Allies should expect continued strong pressure to assume greater defense burdens. In this scenario, the United States will continue to provide its nuclear umbrella; three European-based brigade combat teams; forward divisional and corps headquarters with enablers; one divisional set of pre-positioned equipment; four fighter squadrons based in Europe; the US Sixth Fleet; US European Command; and a US Supreme Allied Commander Europe (SACEUR). In time of war, the US contribution would be reinforced to include four fighter wings, an army corps of two divisions with enablers, and the US Second Fleet. US pressure to assume costs for its presence in countries like Germany is likely. This option could see the United States prioritizing exercises and troop deployments in those countries that meet the administration’s defense spending demands.

The second would resemble France’s withdrawal from the military command structure in 1967, with a much-reduced US presence. This option would see most US ground and air forces withdrawn; retention of the US nuclear umbrella and pre-positioned equipment; trainers and advisers as well as staff representation in NATO structures; and a European SACEUR. In this scenario, the United States will remain committed to Article 5 but only in a reinforcing role, with far greater reliance on Europe.

In a third case, the United States withdraws from NATO, removes its nuclear umbrella, and redeploys its military forces to the United States or the Indo-Pacific region.101Spatafora, “The Trump Card.” In this circumstance, NATO might carry on without the United States, be disestablished, or perhaps function as the military component of an expanded European Union.102For the EU’s assessment on “the way forward for European defense,” see: “Joint White Paper for European Defence Readiness 2030,” European Commission, March 19, 2025, https://defence-industry-space.ec.europa.eu/document/download/30b50d2c-49aa-4250-9ca6-27a0347cf009_en?filename=White%20Paper.pdf. Should the Alliance fold altogether, a regional coalition or consortium including the Nordic and Baltic states, Poland, and perhaps the United Kingdom (UK) could evolve.

This study assumes a reduced US presence in Europe, continued US extended nuclear deterrence, and a US SACEUR. As mentioned above, proposed solutions for the threats and challenges presented herein assume limited US participation. With these considerations in mind, the following discussion will examine possible scenarios for further aggression in the Nordic and Baltic region along with suggested solutions for deterrence and defense.

In all the scenarios discussed below, certain factors apply. Any Russian military operation to seize NATO territory will be preceded by an assessment of expected Alliance reactions; if the chances of a robust response are considered low, the probabilities that Russia might act increase. The scenarios considered here could unfold in isolation or in tandem. Russian diplomacy will focus on support for nationalist or right-wing parties in order to generate dissensus inside NATO and the EU. Russian forces based in western Russia, such as 1GTA, must first be reconstituted, reequipped, and returned to full strength. Any operation will be fully joint, involving air, sea, land, space, and cyber domains. In all, intelligence preparation of the battlefield will be intense, and Russia will deploy disinformation, espionage, and sabotage. Indicators of a pending operation might include redeployment of air and sealift platforms; increased aerial and maritime reconnaissance; increased activity of rapid intervention forces; stepped-up disinformation; and no-notice snap exercises intended to mask actual operations. Russian SOF will participate and will probably precede the introduction of conventional forces. Military deception, such as the use of civilian shipping and commercial air transport and diversionary operations elsewhere, should be expected. A “cold start” using elite intervention forces (e.g., naval infantry and airborne units) is more likely than extensive mobilization that might alert NATO forces in advance. Finally, the timing of Russian aggression might be linked to climactic conditions and time of year, Western political transitions or domestic unrest, or crises such as conflict in the Indo-Pacific or Middle East that might hinder effective responses.103Andrea Kendall-Taylor, et al., “Understanding Russia’s Calculus on Opportunistic Aggression in Europe,” Center for a New American Security, September 4, 2025, https://www.cnas.org/publications/reports/understanding-russias-calculus-on-opportunistic-aggression-in-europe.

Target 1: Svalbard archipelago

Undefended and far from military assistance, the Svalbard archipelago is a tempting opportunity to test NATO resolve and improve Russia’s geostrategic posture in the High North.104“The Kremlin seems to view the [Svalbard] archipelago as a place to test new ways of asserting itself and undermining the West.” See: Elisabeth Braw, “We Need to Pay Closer Attention to Svalbard,” Politico, March 26, 2025, https://www.politico.eu/article/we-need-to-pay-closer-attention-to-svalbard/. A sudden, uncontested military occupation by Russian troops would pose a severe test for both Norway and the Alliance. Located 750 kilometers (km) north of the Norwegian mainland in the Norwegian Sea, the archipelago includes Svalbard (formerly Spitzbergen), Hopen, and Jan Mayen islands. In accordance with the 1920 Svalbard Treaty, the archipelago is sovereign Norwegian territory but subject to a number of stipulations: military installations cannot be placed there; citizens of any treaty signatories can reside and pursue commercial opportunities on the islands, subject to Norwegian law; and all parties must respect and preserve the local environment.

The archipelago is sparsely populated, with fewer than three thousand residents spread across seven locations and only two permanent settlements (Longyearbyen and Barentsburg, on Svalbard island). Seventeen percent of its population is made up of Russian nationals. Its principal mineral resources are coal, zinc, copper, and phosphate. Norway operated a single coal mine that exports 80,000 tons annually to European customers, but it closed in 2025.105Thomas Nilsen, “Norway Prolongs Coal Mining at Svalbard until 2025,” Barents Observer, September 2, 2022, https://www.thebarentsobserver.com/arctic-mining/norway-prolongs-coal-mining-at-svalbard-until-2025/103395. One local airport supports regular commercial air service to Svalbard from mainland Norway. One of the world’s largest ground-based commercial telecommunications stations is based on the island. It was bombed by Germany in World War II and later used as a weather station by the German military.

In support of its commercial interests—and as allowed by the treaty—Russia has maintained a nearly permanent presence on Svalbard for decades, principally for mining. At the height of the Cold War, Svalbard was home to more than twice as many Russian citizens as Norwegians. A major mining complex at Pyramiden was abandoned in 1998; today it is manned as a research station by twelve Russian nationals. A Russian mining operation remains active at Barentsburg, producing 120,000 tons of coal per year but programmed for reduction to 40,000 tons by 2032.106Heiner Kubny, “Russia to Slash Barentsburg Coal Mining by Two Thirds,” Polar Journal, May 17, 2023, https://polarjournal.ch/en/2023/05/17/russia-to-slash-barentsburg-coal-mining-by-two-thirds. A Russian Geographical Society office opened in Barentsburg in October 2025 as well. The Russian government also encourages tourism from “friendly” countries, raising the Russian profile and footprint on Svalbard. In recent years, Russia has stepped up its complaints, asserting various violations of the treaty concerning fishing rights, treatment of Russian citizens, research activities, Norwegian military activity, and Norwegian claims to an exclusive economic zone (EEZ).107[1] Andreas Østhagen, “The Myths of Svalbard Geopolitics: An Arctic Case Study,” Marine Policy 167 (2024), https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0308597X24001817.

Current Norwegian government documents acknowledge “the risk of military conflict involving Norway [has] increased” and assert that “the exercise of national control in Svalbard is to be strengthened.”108[1] “The Norwegian Defence Pledge,” Norwegian Ministry of Defence, April 5, 2024, https://www.regjeringen.no/en/documents/the-norwegian-defence-pledge/id3032809/; “New Norwegian Long Term Plan on Defence: ‘A Historic Plan,’” Office of the Prime Minister of Norway, press release, April 5, 2024, https://www.regjeringen.no/en/whats-new/new-norwegian-long-term-plan-on-defence-a-historic-plan/id3032878/; “National Security Strategy,” Office of the Prime Minister of Norway, May 2025, 20, https://www.regjeringen.no/en/documents/national-security-strategy/id3099304/?ch=1. Though lacking in military infrastructure, the archipelago represents a potential platform for reconnaissance and surveillance of the Norwegian and Barents Seas and a listening post for observation of the High North, as well as Russian naval activity out of Murmansk and the Kola Peninsula, home to the Russian Northern Fleet.109Andreas Østhagen, Otto Svendsen, and Max Bregmann, “Arctic Geopolitics: The Svalbard Archipelago,” Center for Strategic and International Studies, September 14, 2023, https://www.csis.org/analysis/arctic-geopolitics-svalbard-archipelago. The bulk of the Russian navy is based in the Kola Peninsula, including the majority of Russian ballistic missile and attack submarines, as well as long-range naval aviation.110Captain Christopher Bott, “Responding to Russia’s Northern Fleet,” US Naval Institute Proceedings 147, 3 (2021), https://www.usni.org/magazines/proceedings/2021/march/responding-russias-northern-fleet. If militarized, Russian possession of Svalbard would deny NATO allies this potential advantage and enhance Russian presence and reach in these waters, contributing to a layered defense of the Kola complex and strengthening Russian access to the Arctic Ocean and the North Atlantic. Of note, Norwegian analysts report a strong Russian intelligence focus on the archipelago, as well as the Arctic region and the Northern Sea Route in recent years, highlighting the islands’ geographic importance.111Eugene Rumer, Richard Sokolsky, and Paul Stronski, “Russia in the Arctic—A Critical Examination,” Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, March 29, 2021, https://carnegieendowment.org/research/2021/03/russia-in-the-arctica-critical-examination?lang=en. In January 2022, just weeks before the invasion of Ukraine, a major telecommunications cable from the mainland to Svalbard was cut, almost certainly by Russian commercial vessels.112Schmitt, et al., “Underwater Mayhem,” 36.