The recent increase in Russian military involvement in Syria is widely seen as an expansion of Moscow’s influence in the Middle East. While offensive ambitions may well be present, defensive motives also appear to have played a role in Putin’s decision-making. From Moscow’s perspective, supporting the Assad regime is a defensive goal: Putin does not want to see the downfall of Russia’s last real ally in the Arab world. But Moscow’s actions in Syria are motivated by an even more defensive goal still: preventing greater unrest in the North Caucasus and other Muslim regions of Russia.

The recent increase in Russian military involvement in Syria is widely seen as an expansion of Moscow’s influence in the Middle East. While offensive ambitions may well be present, defensive motives also appear to have played a role in Putin’s decision-making. From Moscow’s perspective, supporting the Assad regime is a defensive goal: Putin does not want to see the downfall of Russia’s last real ally in the Arab world. But Moscow’s actions in Syria are motivated by an even more defensive goal still: preventing greater unrest in the North Caucasus and other Muslim regions of Russia.

But are events in Syria and the Muslim regions of Russia connected? In the view of the Kremlin, they definitely are. As early as 2011, top Russian leaders portrayed the outbreak of the Arab Spring as an effort to incite Muslim rebellion inside Russia. More recently, even official Russian sources have claimed that there are growing numbers of jihadists from Russia—1,700 or even 2,400—fighting in Syria. Moscow greatly fears the prospect that these will return to Russia, along with the Islamic State (ISIS or ISIL), in order to fight there. ISIS itself signaled last year that it intends to spread its campaign to Russia in a video message addressed to Putin himself, complete with Russian subtitles. The video stated, “We will, with the consent of Allah, free Chechnya and all of the Caucasus! … Your throne has already been shaken, it is under threat and will fall with our arrival.”

While ISIS might not pose an immediate threat to Putin, “The Kremlin’s upping the ante in Syria is explained by its vision of IS [ISIS] as a threat to Russia itself,” wrote Dmitri Trenin of the Carnegie Moscow Center (and one of Moscow’s leading authorities on Russian foreign policy) in mid-September. He further noted that, “Fighting the enemy abroad, by bolstering an ally is preferable, of course, to having to fight in the Caucasus or Central Asia.”

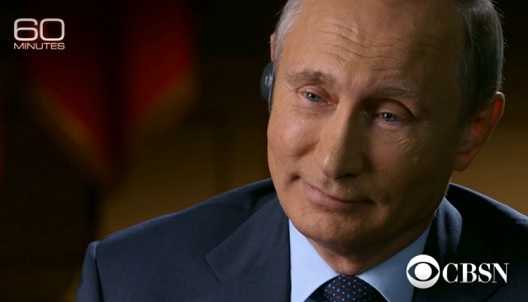

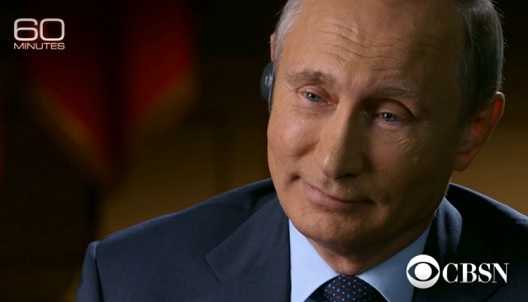

Putin articulated a similar logic in his interview with Charlie Rose that was aired on September 27: “More than 2,000 fighters from Russia and ex-Soviet Republics are in the territory of Syria. There is a threat of their return to us. So instead of waiting for their return, we are better off helping Assad fight them on Syrian territory.”

I have heard this logic expressed many times in conversations over the past few years with Russian interlocutors. It is similar to one of the arguments made by former Vice President Dick Cheney about how the Bush administration had to intervene and remain in both Afghanistan and Iraq in order to prevent jihadists from launching further attacks on the United States from those countries. In his book, In My Time (2011), he wrote, “[We] had to realize that defending the homeland would require going on the offense. Relying only on defense was insufficient. … We needed to go after them where they lived in order to prevent attacks before they were launched.”

The problem with this “fight them there so that we don’t have to fight them here” logic is that it does not necessarily work. While there have been no other jihadist attacks on US territory on the scale of 9/11 after that event, the US presence in Iraq and Afghanistan did not prevent numerous smaller scale attacks, or attempts at them, by US-based disgruntled Muslims or by foreign-based jihadist groups (including Al-Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula). Nor did the US military presence or that of its Coalition partners in Afghanistan and Iraq prevent jihadist attacks in several countries allied to Washington.

Similarly, Moscow’s support for the Assad regime since the outbreak of the rebellion in Syria in 2011 has not prevented the continuation of jihadist attacks inside Russia. Russia has a large Muslim community: 16 million residents of the Russian Federation plus another 4 million or more migrants from Central Asia and Azerbaijan. A recent article by Alexey Malashenko, also of the Carnegie Moscow Center, discussed the increasing radicalization of this community that occurred in the first decade of the twenty-first century (i.e., before the outbreak of the Arab Spring in 2011). A number of jihadist attacks also occurred inside Russia in 2010-12, but these declined afterward.

Discontent with their status inside Russia, not what happens in Syria, appears to be the main reason why many Muslims in Russia turn to radical ideologies and terrorism. Just as the US presence in Afghanistan and Iraq did not eliminate jihadist attacks inside the United States and countries allied to Washington, Moscow’s support for the Assad regime cannot eliminate the causes of jihadist attacks inside Russia. It is highly doubtful that the recent increase in Russia’s military presence in Syria will do so either.

Moscow, it should be noted, has made some efforts to address the concerns of Russian Muslims. Putin’s recent opening of an enormous new mosque in Moscow appears to be a genuine effort to reach out to the Muslim community. But as Malashenko drily noted, “The socioeconomic and political reasons for radical sentiments among Muslims have yet to be eliminated.” Increased Russian military support for the Assad regime will not do this either. If anything, it may inflame those radical sentiments.

Mark N. Katz is a professor of government and politics at George Mason University.

Image: Screen capture of Russian President Vladimir Putin in an interview with Charlie Rose on CBS News, aired September 28, 2015. (Screenshot, CBSN)