Steelmaking takes iron and carbon, and now some gold, too. On Friday, US President Donald Trump approved the long-in-limbo merger of US Steel with Japanese company Nippon Steel, which had been held up for months by the US government on national security concerns. A breakthrough only came after the companies agreed to give the US government veto power over certain aspects of corporate governance, US production, and trade. “We have a golden share, which I control,” Trump explained on Thursday, adding that it would give him “total control” over relevant US Steel business decisions.

Over the weekend, new details emerged about how the share is intended to work, provoking some comparisons with nationalization schemes in other countries. Below, Sarah Bauerle Danzman, a resident senior fellow with the GeoEconomics Center’s Economic Statecraft Initiative, delves into where exactly this deal lands between free enterprise and state control—and what it might mean for other US businesses.

1. What is a “golden share”?

A golden share typically refers to a special class of ownership stake in a publicly traded company reserved for a government. The golden share confers substantial shareholder rights that would otherwise be atypical given the size of the ownership position.

For instance, the Brazilian government has a golden share in Embraer, its national aviation champion, that amounts to an approximately 5 percent equity stake in the previously state-owned company. The arrangement also provides the government substantial governance rights, such as the ability to direct the company’s strategic director or veto a takeover or joint-venture arrangement involving the company.

The United Kingdom has used golden-share arrangements extensively to retain influence over strategically important companies, such as BAE (a major defense contractor) and NATS (its air traffic control provider) after they were privatized.

Reporting suggests that the US government’s golden share is in US Steel rather than in Nippon Steel. This distinction is important because it means that the US government’s formal influence over Nippon will only relate to its US business (called US Steel) and not to its business operations in other locations. By tying the golden share to US Steel, the US government has also ensured that it will be able to fully control any future sale of the company.

2. Does this deal amount to the nationalization of US Steel?

The golden share is “noneconomic,” meaning that it did not require the US government to make an investment in the company, and it also does not provide the United States with an equity stake in the company. This means that the US government will not be earning an economic return on its share, nor would it be eligible to accrue dividends. Additionally, the United States is not going to be involved in the day-to-day operations of US Steel. Because of this, and because the United States is not taking equity stakes away from owners, this is not a nationalization.

However, the golden share gives the US government an extraordinary amount of control over the company. The company’s governance documents will outline the areas of strategic and operational decision making over which the US president will now have veto authority. US Steel may not be state-owned, but it is certainly now controlled by the US government.

3. How will it be enforced?

The golden share will require presidential approval for a range of strategic and operational decisions, including capital allocation and investment decisions. Plainly, Nippon has agreed to an arrangement in which it would need to seek presidential approval if market conditions changed, and it decided it could not fulfill its commitment to invest another fourteen billion dollars into US operations over the next several years.

This raises several questions: How will these requirements be enforced? What if Nippon reduced investments even without presidential approval? How would the US government compel Nippon to increase investments to its promised amount? The enforcement options of the US government are relatively weak here, especially if Nippon finds itself in a fragile economic position. A golden share gives the government substantial strategic control on the cheap, but the US government may find that some elements of its authority would be hard to enforce in a soft economy.

4. What wider implications could this have for US businesses?

A golden share reduces the economic value of the company for other investors, even if the government only takes a “noneconomic” position. That is because the government is reducing the ability of equity shareholders to control the strategic and operational decision making of the company, which could generate costs and inefficiencies for the corporation. If golden shares were ubiquitous, then financing costs would increase and the attractiveness of the United States and US businesses as investment opportunities would decline.

5. How can the US government mitigate these concerns?

The Committee on Foreign Investment in the United States, known as CFIUS, and the president should release more guidance as quickly as possible to make clear the circumstances under which CFIUS would seek to mitigate national security risks through a golden-share arrangement. These should be very rare cases, and the government should make clear its commitment to restraint. Otherwise, what is to stop the US government from always taking a golden share in any cross-border merger of interest?

Further reading

Mon, Jan 8, 2024

The US Steel deal is a test of friendshoring—and the US is failing

New Atlanticist By Sarah Bauerle Danzman

If Washington won’t allow this transaction—involving a buyer from a G7 country—then what foreign buyer would it see as a permissible owner?

Wed, May 28, 2025

Does the Nippon Steel deal reflect a new normal for foreign investment in the US?

New Atlanticist By Sarah Bauerle Danzman

The big question now is if the Committee on Foreign Investment in the United States process has changed in ways that will affect future deals.

Thu, Jun 12, 2025

Seven charts that will define Canada’s G7 Summit

New Atlanticist By

Our experts provide a look inside the numbers that will frame the high-stakes gathering of Group of Seven leaders in Alberta.

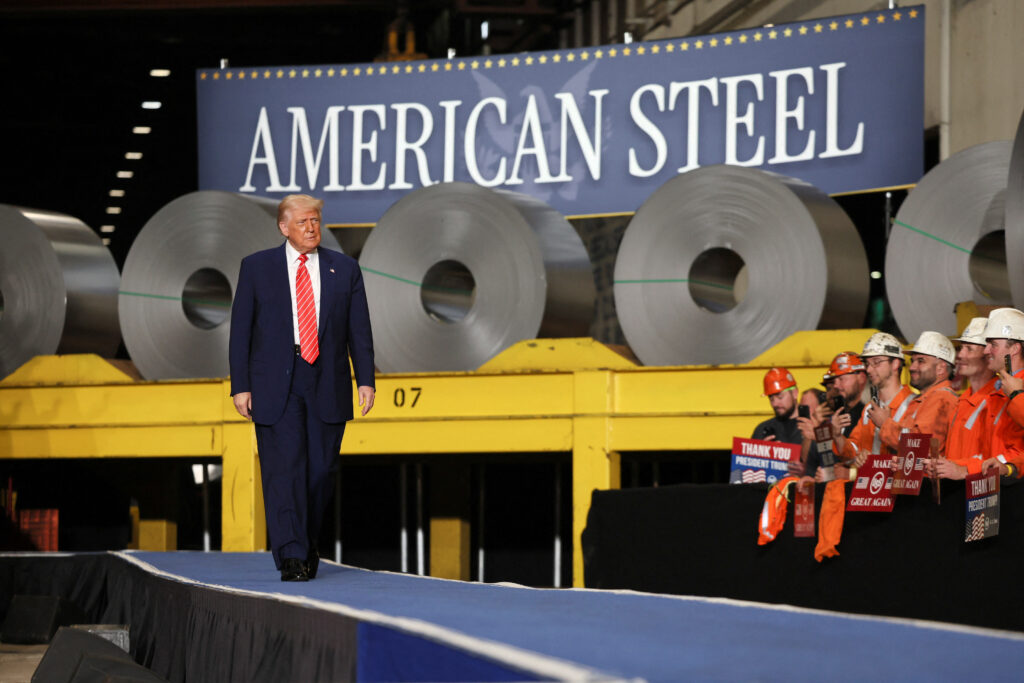

Image: US President Donald Trump walks as workers react at US Steel Corporation–Irvin Works in West Mifflin, Pennsylvania, U.S., May 30, 2025. REUTERS/Leah Millis