In June, the Bolivian government rejected a proposal from the US company Starlink to provide satellite-based internet to the country. The government’s stated rationale was that Starlink’s plan risked violating Bolivia’s sovereignty by handing over too much influence to a foreign company. At the same time, reports surfaced that the Bolivian government was instead holding talks with a Chinese company, SpaceSail, to replace its aging satellites. It was doing so despite SpaceSail’s relatively expensive and cumbersome system, which includes antenna installation that is difficult in some rural communities.

Bolivia’s decision received a fair bit of media attention. In part, this was because it indirectly involved Starlink’s well-known co-founder, Elon Musk. But it was also because the decision appeared to pit two major geopolitical rivals, the United States and China, against one another in a zero-sum competition for influence in the region. This is undoubtedly an evocative picture. The reality, however, is more complex, and the issue of satellite internet in Latin America deserves a closer look. Here are four trends shaping this issue:

1. Satellite internet stands to transform Latin America

High-speed, dependable satellite-based internet could have profound impacts on the region, helping it overcome current gaps and take advantage of new opportunities.

Consider what it could do for education, for example. The COVID-19 pandemic was a brutal wake-up call for the Latin American education sector; studies have shown that students who could not access the internet during the pandemic exhibit significant learning delays. This in turn shapes their career prospects. In a rapidly digitalizing world, access to the internet is closely correlated with job market competitiveness.

Agriculture is another area in which dependable internet could have an impact. Access to the internet gives farmers information about the weather, soil, farming techniques and practices, and market prices. In Colombia, for example, small farmers utilize e-commerce to market their products directly to consumers, bypassing the involvement of retail chains and intermediaries. In Ecuador, smartphone applications such as Agromóvil allow users to follow news on agriculture, as well as the export and import of agricultural products.

Furthermore, studies find that digital financial transfers to alleviate poverty are more effective than cash transfers by hand due to decreased delivery costs. However, the proper infrastructure must be established for such initiatives to be carried out. With the presence of accessible and diverse telecommunications satellite services, poverty gaps can be bridged.

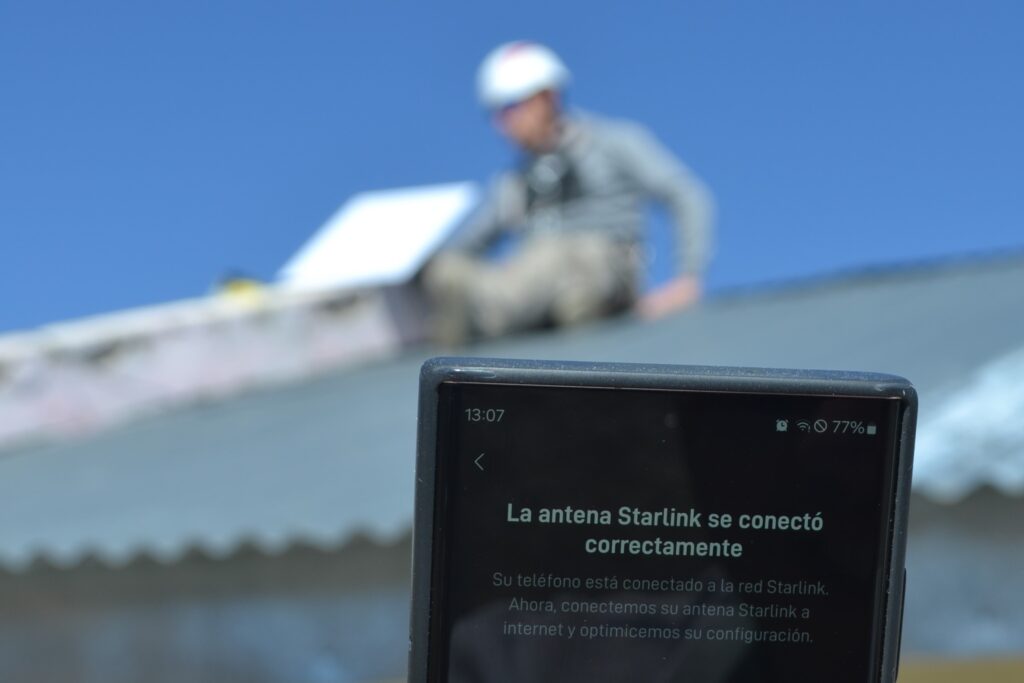

2. Starlink has made major inroads in Latin America

Starlink is the largest satellite internet provider in the world, and it has transformed connectivity in the Brazilian Amazon, for example, by creating dependability that was previously unthinkable. At the same time, Bolivia’s case has highlighted the importance of a competitive and diverse telecommunications satellite sector that can target rural areas. It also highlights the importance of ensuring that domestic interests are represented through telecom satellite providers.

Bolivia is not alone in its concerns about Starlink’s dominance. Brazil, for example, had qualms of its own with Starlink, raising concerns over the company’s influence in the country. In 2024, Starlink refused a Brazilian court order to ban the social media platform X based on disinformation claims.

Starlink’s success in the region can be attractive to some countries for the company’s demonstrated ability to provide service that can close the connectivity gap. At the same time, the company’s very dominance can be a deterring factor for some countries if they worry about one company having too much control over the internet.

As demonstrated in the case of Bolivia, it is into this dilemma that Chinese companies are stepping in and seeking to challenge Starlink’s dominance.

3. China wants to be a major provider, too

In many ways, China’s foray into satellite internet in Latin America is expected. China’s Belt and Road Initiative has already roped in more than twenty countries in Latin America and the Caribbean, influencing projects from health to infrastructure—and space is no exception.

In fact, when it comes to space infrastructure, China has long been present in Latin America, whether that be in an Observatory in the Atacama Desert (Chile) or in Estación Del Espacio Lejano (Argentina). More recently, at a Beijing conference with Latin American leaders, Chinese President Xi Jinping announced his continued intention for collaboration in all “emerging” areas, including telecommunications and artificial intelligence. Echoing Xi’s claims, Brazilian President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva proposed a Brazil-China partnership for the launch of low-orbit satellites for increased connectivity in Brazil’s remote areas.

However, fears over a vertical relationship in satellite technology transfers, though useful in the short run, may run contrary to self-actualized development in the region. Even though China built and launched three Venezuelan satellites into orbit, there was a lack of technological transfers beyond a small training program for Venezuelan technicians.

4. Some Latin American countries are already looking beyond Starlink and SpaceSail

If leaders are hesitant to allow a dominant foreign company to operate in their countries, local companies should seek out partnerships with foreign companies that prioritize their interests.

To an extent, this is already happening. In 2023, the Chilean company Andesat signed a deal with Astranis to launch the first satellite solely dedicated to the people of Peru. At the heart of the deal is the national goal of connecting around three million Peruvians, many in the country’s rural peripheries, to a fast and reliable connection. Similarly, Colombian engineering and telecommunications firm INRED partnered with Luxembourg-based SES under an initiative by the Colombian Ministry of Information and Communication Technologies known as “Zonas Comunitarias para la Paz”. This will provide connection services to historically unconnected areas in the country through SES’s broadband satellites. In 2024, Orbith, an Argentinian telecommunications company, partnered with California-based Astranis on the sale of a small geostationary broadband satellite to serve domestic telecoms demand.

Latin American governments also have a major role when it comes to accessibility. In last year’s Futurecom summit, hosted in São Paulo, leaders in the private telecoms sector called for tax exemptions for the telecommunications industry in order to foster domestic growth. According to the general director at the Brazilian telecommunications company Embratel Star One, economic restrictions imposed by the government lead satellite operators to set up stations outside of Brazil. Government flexibility can help foster a domestic industry that increases competition.

Satellite internet is a rapidly expanding and evolving sector. Even with the current dominance of Starlink and the ambitions of SpaceSail to challenge its dominance, it will likely be a far bigger and more diversified sector in the coming years. Latin American countries must think creatively and learn from their peers to determine what works best in closing the connectivity gap.

Olivia Torres is an intern at the Atlantic Council’s GeoTech Center and a rising senior at Wellesley College studying international relations-political science, with a minor in Latin American studies.

Further reading

Wed, Oct 2, 2024

China’s cleantech growth strategy sets its sights on Brazil

EnergySource By Joseph Webster, William Tobin

China is relying on cleantech exports to help drive economic growth, but with the United States and other developed nations becoming increasingly hesitant to purchase Chinese imports, China’s cleantech sectors need to search for alternative markets. Brazil has emerged as a potential top buyer, but it must walk a fine line to avoid becoming overly dependent on China.

Mon, Jul 21, 2025

Navigating the new reality of international AI policy

GeoTech Cues By Evi Fuelle, Courtney Lang

To reach their goals of national AI adoption, governments must continue to advance the global policy discussion on trust, safety, and evaluations.

Wed, Jul 2, 2025

To avoid an AI data-center bubble, Washington must change how it works with US states

New Atlanticist By Trisha Ray

Without better state-federal coordination, the United States risks sinking billions into stranded capacity, with taxpayers footing the bill.

Image: Rio Negro, Argentina.- In the photos, the town of Ojos de Agua in the province of Rio Negro, Argentina works on the Starlink high-speed internet connection on September 13, 2024. Starlink offers satellite internet services that stand out for their high speed and their ability to reach remote areas where traditional connections are often deficient. Since its launch, the company revolutionized internet access in various parts of the world, by providing an innovative alternative in countries with limited infrastructure. REUTERS