Moses parts the Red Sea: Israel’s strategic challenges as new routes emerge

A new $4 billion bridge across the Strait of Tiran could upend plans to physically integrate Israel into the Middle East.

In a big step reshaping Red Sea connectivity, Saudi Arabia and Egypt have recently announced finalized plans for the Moses Bridge, a thirty two-kilometer causeway linking the Saudi coast of Ras Hamid with Egypt’s Sinai Peninsula at Sharm el-Sheikh. Named after the biblical tale of Moses parting the Red Sea, this ambitious megaproject aims to physically connect Asia and Africa, bolstering trade, tourism and pilgrimage routes between the Gulf and North Africa. Fully financed by Riyadh, the initiative reflects Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman’s broader infrastructure diplomacy under Vision 2030, and it marks a shift from decades of discussion toward implementation.

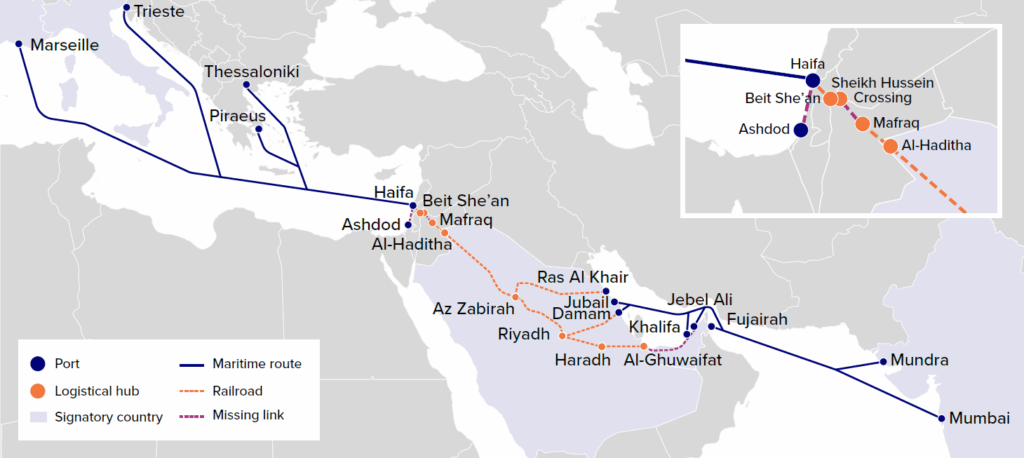

The project carries important geopolitical and economic implications for the region. While the bridge promises logistical gains and deeper Gulf–Africa integration, it also poses strategic challenges, particularly for Israel. The new land link bypasses Israel entirely, creating an alternative to the proposed India–Middle East–Europe Economic Corridor (IMEC), in which Israel was expected to serve as a key transit node. Together with emerging land corridors through rehabilitated Syria and Iraq, the Moses Bridge highlights a possible future in which Israel is excluded from regional integration if political tensions persist.

These alternative routes may challenge Israel, but they should also serve as a wake-up call about what is at stake and what is possible. Israel should resist viewing these new corridors as a zero-sum threat; rather, the multiple transit routes can coexist and even complement one another if approached with strategic foresight and pragmatism. Perhaps most important, the United States and Israel must treat these developments not as competition to outmaneuver, but as momentum to harness; through coordination, quiet diplomacy, and shared economic gains.

From vision to reality: The Moses Bridge

The Moses Bridge project reflects Saudi Arabia’s and Egypt’s intent to diversify connectivity on their own terms. Originally proposed decades ago, and agreed in principle by Saudi King Salman and Egyptian President Abdel Fattah el-Sisi in 2016, the plan gained momentum after Egypt transferred the strategic Tiran and Sanafir islands to Saudi Arabia in 2017—removing a major diplomatic hurdle.

In June 2025, nearly a decade later, with planning finalized and diplomatic sensitivities resolved, Egyptian Transport Minister Kamel al-Wazir confirmed that all planning for the Red Sea bridge is complete and that construction can begin “at any time,” pending final approval.

The project’s strategic location is critical. The Strait of Tiran is the gateway to Israel’s only Red Sea port, Eilat, and falls under international guarantees stemming from the Camp David Accords. However, with US-backed security assurances in place, Israel has not opposed the plan.

From a logistical standpoint, the Moses Bridge has the potential to significantly streamline regional trade and travel. Designed to support both road and potentially rail traffic, it is expected to connect with Saudi Arabia’s expanding rail network and Egypt’s developing infrastructure in Sinai. The bridge will also support Saudi’s NEOM megacity project, which lies near the Saudi endpoint. Officials estimate the bridge could serve over one million travelers annually, including pilgrims traveling directly from North Africa to Saudi Arabia’s holy cities. By offering an overland alternative, the bridge may ease pressure on maritime chokepoints and help reduce transit times and shipping costs, particularly important given the recent financial strain on the Suez Canal caused by Houthi disruptions in the Red Sea.

For Saudi Arabia, the project represents far more than a civil engineering ambition; it is a cornerstone of the kingdom’s broader geo-economic strategy. Vision 2030 prioritizes infrastructure development as a means to transform Saudi Arabia into a logistical powerhouse connecting Africa, Asia, and Europe—with the goal of ranking among the world’s top ten logistics hubs. In this context, the bridge is not merely a connector of land masses, but a strategic tool of influence, physically linking continents while reinforcing Saudi Arabia’s role as an indispensable regional nexus for connectivity and commerce.

The IMEC Context: Israel’s bypassed role

The Moses Bridge has emerged at a time when regional powers are racing to establish East–West connectivity. At the 2023 Group of Twenty (G20) summit, the United States, India, Saudi Arabia, the United Arab Emirates (UAE), and the European Union (EU) announced the IMEC initiative, a proposed trade corridor linking Indian ports to Europe via the Gulf and Israel. The plan included two legs: an Indian Ocean maritime link to the Arabian Peninsula, and a northern overland route through the UAE, Saudi Arabia, Jordan, and Israel to Mediterranean ports.

For Israel, IMEC was a strategic boon, offering both economic and diplomatic benefits by generating transit revenues and attracting foreign direct investment. Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu described the corridor as a “blessing of a new Middle East that will transform lands once ridden with conflict and chaos into fields of prosperity and peace.” It aligned with the momentum of the Abraham Accords and the vision of Israel as a vital partner in regional logistics and trade.

However, the IMEC project faces headwinds. The outbreak of war in Gaza in late 2023 dulled regional enthusiasm and put Saudi–Israeli normalization talks on hold, casting doubt over Israel’s political reliability as a partner. Meanwhile, regional actors started to diversify their options.

Saudi Arabia’s strategic hedging

The Moses Bridge reflects Saudi Arabia’s broader hedging strategy. Riyadh is investing in multiple corridors: east to India, west to Africa, and north through Iraq, and Syria to Turkey. All these routes sidestep Israel. While the IMEC plan placed Israel at the center, the Moses Bridge allows Saudi Arabia to connect to Europe independently, through Egypt’s Mediterranean gateway, offering a depoliticized alternative that avoids the risks of entanglement in the Israeli-Palestinian conflict.

Saudi officials have been clear on this front. In October 2024, Saudi Foreign Minister Prince Faisal bin Farhan reiterated that normalization with Israel is “off the table” until there is a “resolution to Palestinian statehood.” Moreover, recent polling indicates that 81 percent of Saudis oppose normalization with Israel, a figure that reflects deep public resistance to engagement with Israel absent meaningful progress on Palestinian rights. With tensions high and public opinion hostile, the kingdom is unlikely to embrace infrastructure projects tied to Israel in the near term.

Egypt’s expanding role

Egypt, for its part, sees this as a way to reinforce its own logistics ecosystem, ensuring that freight coming over the Moses Bridge can move efficiently to ports such as Port Said or Damietta. The bridge integrates with Egypt’s national transportation and logistics strategy, which includes investments in new east–west rail lines, port upgrades on the Mediterranean, and logistics zones in the Sinai Peninsula. It could also help boost tourism in Sharm el-Sheikh, a hub in the Sinai Peninsula.

Cairo is also eager to reduce its reliance on the Suez Canal, whose revenues have dropped by nearly 50 percent amid Red Sea tensions, by expanding overland trade routes. If successful, this infrastructure could help Egypt reposition itself as a land bridge between Africa, the Gulf, and Europe; again, bypassing Israel.

Beyond the Moses Bridge, two additional overland routes have been discussed: the gradual reopening of Syria, which could reconnect Gulf states to Turkey via Saudi Arabia or Jordan, and Iraq’s proposed “Development Road,” linking the al Faw Grand Port to Turkey. Both offer theoretical alternatives, though each faces significant financial, political, and security hurdles.

Geopolitical implications for Israel

Taken together, these developments suggest several overland alternatives that could reduce the strategic necessity of Israel as a transit center. The Moses Bridge is more than a physical connection, it is a strategic message. Saudi Arabia and Egypt are building the infrastructure of a post-conflict Middle East that might no longer depend on Israel. For the United States, this shift can erode one of its potential key channels of influence in the region. As other regional actors, including: Syria, Iraq, and Turkey rejoin the economic conversation, and Arab partners appear indifferent to explore other routes, Israel must act to reinstate its geopolitical advantage.

Recent diplomatic signals reinforce this shift. During his May 2025 Gulf tour, US President Donald Trump visited Riyadh, Doha, and Abu Dhabi, but conspicuously skipped Israel. In remarks delivered in Riyadh, he proposed new economic incentives to Saudi Arabia without linking them to normalization with Israel, a striking departure from past US policy that underscores shifting regional priorities. The message was clear: The Middle East’s road to Washington no longer necessarily runs through Jerusalem.

Strategic pathways forward

How should Washington respond to these developments? To begin with, the United States should assume a more proactive leadership role in advancing IMEC and coordinating with parallel initiatives. This includes fostering multilateral working groups among Israel, Egypt, India, Jordan, and Gulf states; encouraging interoperability between infrastructure projects; and providing political cover and technical support to accelerate implementation. A consistent US presence is essential to prevent fragmentation and ensure that economic corridors deliver on their strategic promise.

In parallel, the United States should elevate IMEC as a strategic priority. The corridor anchors Washington’s influence in the infrastructure domain, counterbalancing the influence of rival powers while reinforcing ties between its allies in the region. To achieve this, it could embed IMEC into national economic and foreign policy frameworks through interagency coordination, perhaps by appointing a dedicated envoy or task force. It could also take steps to integrate corridor diplomacy into the operational workflows of the State Department, National Security Council, and Department of Commerce. Such measures could help ensure continuity across administrations, demonstrate long-term US commitment to regional partners, and allow Washington to better align connectivity infrastructure with its broader geopolitical interests.

More broadly, both the United States and Israel should advocate for a depoliticized framing of IMEC—one that emphasizes mutual economic and logistic benefits rather than symbolic normalization. Quiet diplomacy that underscores shared interests in connectivity, climate adaptation, food security, and digital infrastructure may create space for engagement with Arab and Muslim states still cautious about ties with Israel.

Israel, for its part, must respond not with alarm, but with action. Rebuilding trust with Saudi Arabia should be a top priority. The cease-fire agreement in Gaza offers a window to re-engage regional partners: sustained de-escalation, paired with meaningful steps toward a sustainable and hopeful future for Palestinians, could help revitalize stalled dialogue and restore confidence among Arab states.

Finally, Israel should invest in its own logistical infrastructure, especially in digitization and artificial intelligence–powered logistics. Doing so will enhance its attractiveness and make participation in IMEC and future corridors more compelling.

If approached pragmatically and in close coordination with Washington, Israel can still position itself as a valuable partner; not just within IMEC, but in an emerging web of regional corridors. The window is open, but not forever.

Amit Yarom is a graduate student at the Elliott School of International Affairs at George Washington University. He is a foreign policy researcher, specializing in the Arabian Gulf.

Further reading

Fri, Sep 19, 2025

How Israel’s strike on Doha is forcing a Gulf security reckoning

MENASource By

The Gulf monarchies have displayed strong unity at a time when rethinking twenty-first-century Gulf security is no longer optional.

Fri, Sep 26, 2025

The Saudi-Pakistan defense pact highlights the Gulf’s evolving strategic calculus

MENASource By

In Riyadh’s multi-aligned policy, signing a mutual defense deal with Pakistan is complementary, not alternative, to US security guarantees.

Thu, Jul 31, 2025

Gateways to the Red Sea: The case for Israel–Somaliland normalization

MENASource By

Expanding the Abraham Accords to Somaliland could quietly anchor a more stable and cooperative Red Sea region.

Image: Sharm El Sheikh and Straits of Tiran, satellite image. North is at top. The coastal resort of Sharm El Sheikh is at left, on the Egyptian shores of the Red Sea, on the southern tip of the Sinai Peninsula. At lower centre and lower right are the islands of Tiran and Sanafir (in the Straits of Tiran), at the southern end of the Gulf of Aqaba. Coral reefs at Sharm El Sheikh (in shallow waters, light blue) form a major tourist and diving attraction. At upper right is part of the mainland of Saudi Arabia, the sandy headland of Ras Alsheikh Hamid. Image data obtained by the Copernicus Sentinel-2 satellites on 11 April 2017.No use: BBC, Pearson, Oxford University Press, Springer Nature, Dorling Kindersley, Cambridge University Press & Assessment, New Scientist, Bonnier Publications, John Wiley & Sons, The Lancet, BMJ