Afghanistan, home to over forty million people, today stands under the rule of an ideological movement that has transitioned from an insurgency to a de facto government. The Taliban’s return to power in August 2021 did not result from a popular mandate but from a confluence of systemic failures. Chief among these was a strategic recalibration by the United States and its allies, culminating in a negotiation process in Doha that excluded meaningful participation by the Afghan people. The resulting agreement, reached in their absence, further weakened an already fractured and often corrupt political elite, accelerating the collapse of governance. In prioritizing geopolitical interests, diplomacy, and regional engagement, Western powers effectively abandoned their commitments to human rights and the will of the Afghan population. This retreat enabled the Taliban to reimpose a repressive regime marked by sweeping restrictions on women’s rights and freedoms.

This time, however, the Taliban’s approach is more calculated. Its goal is not merely to rule but to sustain its rule. Unlike in the 1990s, when the curtailment of women’s rights and suppression of civil liberties were driven primarily by rigid ideological interpretations rooted in the teachings of madrassas in Pakistan, the current restrictions are a fusion of ideology and political strategy. The Taliban now understands that restricting education, civic participation, and the political awakening of youth and women is essential to neutralizing long-term threats to its grip on power.

Informed by the trajectories of other ideological regimes—particularly that of the Islamic Republic of Iran—the Taliban appears to have some absorbed important lessons. After the 1979 revolution, Iran imposed strict religious codes and social restrictions yet allowed continued access to education for women. Over time, this decision inadvertently enabled the rise of an educated and politically conscious population—one that today represents a significant challenge to the Iranian regime. The Taliban, however, has chosen the opposite path: to deny women access to education and employment altogether, effectively cutting the roots of future opposition before it can grow.

From the outset, policies restricting girls’ education, women’s employment, and youth expression have not been temporary or incidental. Rather, they are integral to a broader strategy of ideological entrenchment and political consolidation. The excuses provided by some in the regime—the notion that Afghan society is not prepared to accept women in public and in leadership roles, logistical limitations, or undefined “Islamic frameworks”—are tactical deflections meant to obscure the Taliban’s true intent: to silence the country’s most capable agents of transformation.

Yet, despite the regime’s efforts, the people of Afghanistan, particularly its women and youth, continue to organize, advocate, and strategize, both within the country and across the diaspora. They are risking their lives protesting, documenting human rights violations, educating girls in underground schools, and building solidarity across communities and borders. These individuals and communities are not merely resisting; they are actively reimagining a future Afghanistan.

What needs to be done

Legal, diplomatic, and political pressure on the Taliban must be sustained, particularly around issues of human rights, gender equality, and inclusive governance. At the same time, the path forward must also include constructive, meaningful, and targeted engagement that centers the Afghan people themselves. Recognizing and supporting the agency of Afghans, especially women, youth, and civil society actors, must become a strategic pillar of international policy toward Afghanistan.

Afghans inside the country, as well as those in exile, are actively envisioning and building models for a peaceful, inclusive future. Their efforts represent the most credible and locally grounded alternatives to the Taliban’s extremism and authoritarianism. Ultimately, it is about building on the resilience and leadership that persist within Afghan communities despite repression and exclusion.

One example of this is the Strategizing a Seat at the Table (SSTI) initiative, facilitated by Women for Peace and Participation, an organization which I founded in 2012 and where I currently serve as director. This initiative brings together hundreds of Afghan women, including young women from both within and outside the country, in a series of strategic dialogues aimed at shaping policy, proposing solutions, and advocating for inclusion. It is rooted in an ecosystem model that emphasizes complementarity, where different positions, experiences, and capacities across the population of Afghan women are leveraged to advance a collective agenda. This agenda is not limited to women’s inclusion, encompassing other historically excluded groups in Afghan society. Building on this foundation, SSTI trains women in negotiation, mediation, and advocacy; connects them to international platforms; and supports grassroots projects in healthcare, education, and community resilience. By engaging with key forums like the exclusionary Doha Process, United Nations bodies, and local mechanisms, it offers a flexible framework that enables Afghan women not only to participate—but to lead.

Initiatives like this one are part of a growing movement connecting Afghans inside and outside the country to reimagine leadership, redefine governance and assert a new vision for Afghanistan. Media outlets such as Rukhshana and Zan Times amplify voices across generations to advocate for women’s rights and social justice. Organizations like Rawadari document atrocities and pursue justice through international legal accountability mechanisms. Meanwhile, the Women Advocacy Committee of the Women and Children Research and Advocacy Network has established a platform in Canada to represent women leaders and organizations in exile. Women’s Rights First, a women-led organization, promotes gender justice, expands women’s access to justice, and strengthens accountability for human rights violations in Afghanistan.

On the ground in Afghanistan, despite severe repression, women-led resistance continues. These protest movements take many forms: some publish anonymous videos, others run underground schools, and many engage in decentralized, grassroots organizing to resist the systematic erasure of women’s presence, rights, and agency.

Investing in Afghanistan’s future

The Taliban’s model of control today is not simply a product of ideological conviction—it is a deliberate political strategy aimed at long-term dominance. Educated youth and empowered women pose a threat not just because they oppose the Taliban, but because they embody an alternative vision for the nation: one rooted in rights, human dignity, participation, and accountability.

If Afghanistan is to reclaim its aspirations for freedom, equality, and an end to gender apartheid, it will do so through the leadership of those the Taliban seeks to silence. Ensuring these voices are protected, amplified, and resourced is not just a moral imperative, it is the only viable path forward.

Quhramaana Kakar is a peace strategist, mediator, and leadership expert with over two decades of experience advancing women’s inclusion in peacebuilding and women’s socioeconomic empowerment expert across conflict and post-conflict contexts, particularly in Afghanistan. She is the founding director of Women for Peace and Participation and a senior strategic advisor to the Women Mediators across the Commonwealth network, and a fellow at the Centre for Women, Peace and Security at the London School of Economics.

Further reading

Thu, May 29, 2025

How the Taliban is using law for gender apartheid, and how to push back

New Atlanticist By

To combat the Taliban’s institutionalization of gender apartheid, international actors must document the system of lawmaking that underpins the regime's human rights abuses.

Mon, Nov 25, 2024

A protester’s story from inside a Taliban prison

Inside the Taliban's gender apartheid By

Narges Sadat recounts the conditions she was forced to endure in a Taliban prison for protesting Afghanistan’s gender apartheid regime.

Tue, Sep 10, 2024

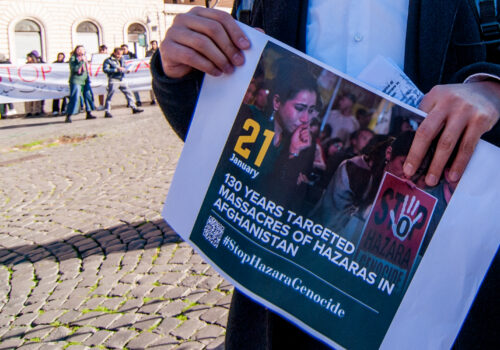

‘The death of Hazaras is permissible.’ What it’s like to protest the Taliban as a minority woman.

Inside the Taliban's gender apartheid By

Tamana Rezaei recounts the compounding dangers she faced as a woman and member of the Hazara minority protesting the Taliban’s rule.

Image: Hosna Salehi, whose family runs a charity called the House of Kindness, writes on a white board as she teaches children inside a classroom in Herat, Afghanistan, October 27, 2024. Reuters/Sayed Hassib.