Following the Taliban’s 2021 takeover of Kabul, Narges Sadat took to the streets in protest along with other women. She faced violence and imprisonment, a story she recounts below.

I was born in Karaj, Tehran, and after many years in Iran, I returned to Afghanistan to work. At that time, Afghan women were beginning to engage with democracy and reclaim their place in public life, but the Taliban attacked this progress with a relentless assault on civilian life. The group destroyed infrastructure; attacked schools, universities, and hospitals; and ultimately seized control of the country before imprisoning women in their homes.

Days before the Taliban entered Kabul, Kandahar had fallen. My mother and siblings fled to my home in Kabul, leaving everything behind as our father’s house in Kandahar was surrounded by Taliban forces, who arrested the men in our family.

On August 15, 2021, I saw Taliban fighters in the streets as I attempted to reach my office. They were on motorcycles and in military vehicles, brandishing white Taliban flags, their faces weary yet triumphant. People were fleeing in terror. Unable to reach my destination, I turned back, a journey that stretched for hours due to the chaos. In the sixth district, Taliban soldiers angrily lowered Afghanistan’s tricolor flag, replacing it with their own.

The sight of people’s panic and the violent, angry faces of the Taliban terrified me. I began to fear that they would notice my uncovered face. At one point, a Taliban soldier slammed the car I was in and demanded to know, “Who is this, and where are you taking her?” The driver, thinking quickly, responded, “She is my daughter, and I’m taking her home.” Later, near the American University, the sounds of gunfire filled the air, and I broke down in tears.

My husband and I were on an evacuation list, but when we attempted to reach the airport with a single bag of clothes, we turned back in fear after witnessing a deadly explosion there. On the way home, I saw the Taliban whipping a woman over her clothing. Her husband pleaded for leniency, but they insulted him too, accusing him of dishonor for allowing his “bad wife” to go out in public. This is how gender apartheid operates under the Taliban—not only imposing strict regulations on women but also systematically turning men in the family into enforcers of the Taliban’s control over women.

The following day, I learned that women were banned from working. I was permitted only to collect my belongings from the office. Drivers, however, had been instructed not to pick up women who were alone or not fully covered in hijab. Waiting hours for a ride, I faced jeers from Taliban fighters, who hurled insults at women to cover their faces.

Humiliated and isolated, I decided to later join other women at the Fawara Aab, the water fountain square, to protest. My mother had taught me to resist, not to stay silent. And with no job or income, resistance through protest was our only choice. Abandoned by the international community, Afghan women were left alone to face the Taliban’s repression and apartheid regime.

When we protested, men on the streets accused us of seeking an excuse to leave Afghanistan, questioning our motives. But our revolution was all we had left. On August 13, 2022, a year after the Taliban takeover, we gathered to protest again. We met at Kabul’s Golbahar Center, but soon, Taliban forces surrounded us, firing shots into the air. They pursued us, firing directly at us as we reached Jamhuriat Hospital. Injured and separated, ten of us took shelter in an underground space. The owner, who initially reassured us, ultimately betrayed us and called the Taliban. When they arrived, the Taliban soldiers beat us with Kalashnikov rifles, accusing us of dishonoring our families. After confiscating our phones, they detained us for three hours before releasing us, though they kept us under surveillance.

On February 9, 2023, the Taliban arrested me again, dragging me from a taxi at a checkpoint and dispersing the crowd by firing shots to prevent there from being any witnesses. They took me to a security facility, where thirty armed men awaited. One of them threw a cup of hot tea at me when I told them I was from Kandahar, and I feared I had gone blind. They forced me to unlock my phone by prying my fingers, then beat me when I asked to see my family.

Around 11:30 pm, they took me to the intelligence office, twisting my arms when I resisted. Two women were brought to escort me, placing a black hood over my head. We reached Dehmazang, where they photographed me like a criminal and led me to a damp, dark cell. I was bleeding heavily, and after I fainted, they took me to the hospital under strict orders to hide my face. There, I whispered to the doctors, “I am Narges Sadat, the girl who protested and was arrested by the Taliban. They can’t silence me.” Some of the doctors even cried but could do little beyond applying ointment to my wounds.

Back in prison, they beat me and denied me sanitary items. I scratched words onto the cell walls with my nails, recounting what had happened. I saw traces left by other protesting girls who had been held there before me.

Each time they whipped me, they declared the reason: “Because you messaged other protesting women, because of your protests, because you posted photos of Ahmad Shah Massoud and General [Abdul] Raziq,” military leaders who resisted the Taliban. Their accusations piled up. When Eid approached, I hoped for release, as others had been pardoned. A prison official called my name, but instead of freedom, he accused me of causing trouble in the prison, calling me a mercenary and servant of foreigners. My nine-year-old son visited me, terrified, asking them to free me. They told me they would release me if I pledged to stop protesting. Desperate to be with my son, I agreed. After taking a heavy “guarantee” from me, they finally let me go.

In total, I was in Taliban custody for eighty days (though their official record falsely stated sixty), including thirty-five in solitary confinement. They tortured me with electric shocks and left cold water beneath my feet at night. I was denied family visits, and each trip to the bathroom involved being hooded and led several floors up in excruciating pain.

When transferred to the general cell, the pain only intensified. There were other women imprisoned with their children in deplorable conditions. Some had severe mental health issues, worsened by confinement. Girls as young as ten and fifteen were jailed because their male relatives had served under Raziq, a commander in the Afghan army who was assassinated by the Taliban in 2018. Other young women faced the threat of stoning, accused of fleeing their homes.

I even witnessed women in the prison who were affiliated with the Islamic State of Iraq and al-Sham (ISIS) enjoying better conditions than ours. They were granted cell phones, water filters, and a variety of food. They often bullied other inmates, and once, they physically assaulted me.

Reflecting on my traumatic ordeal, I realize that perhaps my time in prison was part of my purpose. I endured to speak out for the women still silenced within those walls. The Taliban prison is a place where calls to prayer mix with women’s screams. We took to the streets not just for ourselves but to demand equality and resist the Taliban’s apartheid regime.

Our resistance is rooted in a long history. We are the daughters of women whose lives were stolen by the Taliban, who taught us to resist through their own stories of suffering. Today, the world’s fleeting support reminds us of Afghan women’s bravery, but we are now abandoned to a terrorist authoritarian regime that decides our fate as the world watches. Yet we will continue to rise, defying the Taliban’s will with renewed strength each day.

Today, we call on countries that claim to champion human rights to recognize gender apartheid as a crime. Our testimonies provide undeniable proof of this regime’s repressive nature. The sexual assaults on women protesters in Taliban prisons, the Taliban’s public announcements of stonings, and decrees from their Supreme Court and Amir al-Momineen establish a foundation for defining gender apartheid in Afghanistan.

To achieve a safer and more just world, gender apartheid must be recognized as a crime, and the Taliban must face accountability in international courts.

Narges Sadat is an advocate and women’s rights activist from Afghanistan. She garnered international attention for her protests against the Taliban’s gender apartheid. She graduated in the fields of literature, administration, and diplomacy.

This article is part of the Inside the Taliban’s Gender Apartheid series, a joint project of the Civic Engagement Project and the Atlantic Council’s Strategic Litigation Project. This article is based on an interview with Sadat by Nayera Kohistani and was translated and edited by Mursal Sayas.

Further reading

Tue, Sep 10, 2024

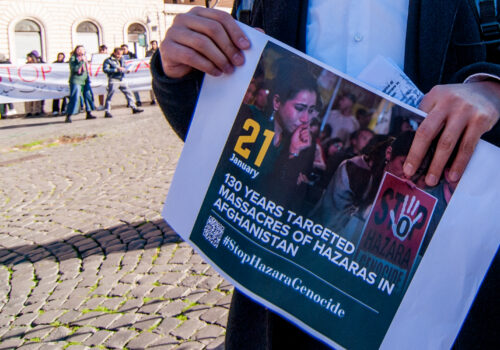

‘The death of Hazaras is permissible.’ What it’s like to protest the Taliban as a minority woman.

Inside the Taliban's gender apartheid By

Tamana Rezaei recounts the compounding dangers she faced as a woman and member of the Hazara minority protesting the Taliban’s rule.

Mon, Aug 26, 2024

The Taliban’s violence ‘ignited a fierce resistance within me.’ A protester’s story.

Inside the Taliban's gender apartheid By

Nayra Kohestani recounts the abuse and imprisonment she and her children suffered for resisting the Taliban’s gender apartheid regime.

Wed, Aug 14, 2024

I was imprisoned and tortured by the Taliban for protesting gender apartheid in Afghanistan

New Atlanticist By

Zholia Parsi describes protesting against gender apartheid in Afghanistan after the Taliban returned and abuse she faced as a result.

Image: An Afghan woman holds up a placard during a rally to protest against what the protesters say is Taliban restrictions on women, in Kabul, Afghanistan, December 28, 2021. REUTERS/Ali Khara.