When the Taliban seized power in 2021, the women of Afghanistan’s hard-won rights were swiftly erased. Bans on education, employment, and even access to public spaces reflect not incidental repression but a deliberate policy of gender apartheid. This daily reality parallels South Africa’s apartheid regime, where exclusion and domination were legally enforced to maintain control.

I recently spoke with Gertrude Fester, a veteran South African anti-apartheid activist, and Munisa Mubarez, a women’s rights advocate from Afghanistan, to explore how the lessons of South African women’s resistance offer strategic guidance and moral courage for the women of Afghanistan today.

Women mobilizing: From South Africa to Afghanistan

Throughout history, women have been at the forefront of resistance against oppressive regimes, often at great personal risk. In Afghanistan, despite extreme Taliban restrictions, women continue to organize. They have protested in Kabul, Mazar, and Herat, demanding their rights to education, work, and dignity. Underground schools have emerged, secret economic initiatives have been developed, and digital activism continues to challenge Taliban censorship.

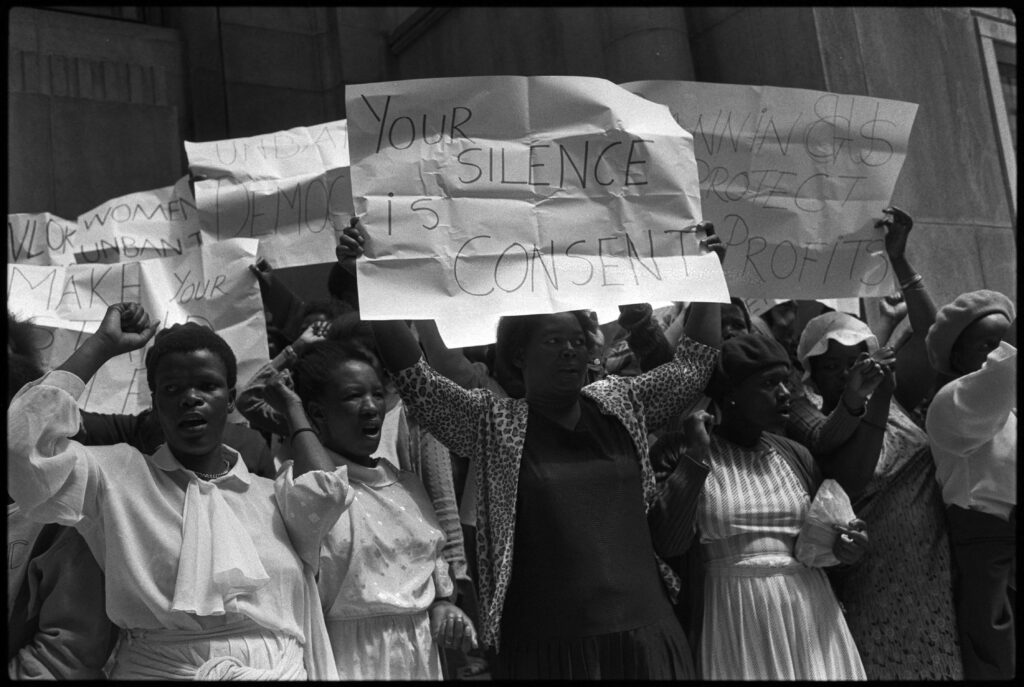

Their fight is not new. South African women, too, were central to the struggle against apartheid, refusing to be silenced despite state-sanctioned brutality. In 1956, twenty thousand South African women—Black, Indian, and Colored (a South African term for multiracial)—marched to Pretoria to protest “pass laws” that restricted their movement. “Women didn’t just stand behind the struggle; we were at the front. We organized, we led, and we shaped the movement,” recalls Fester. She emphasizes that activism must “start where women are—in their homes, villages, and everyday lives.”

Mubarez echoes this for Afghanistan: “Change doesn’t come from the top. We have to raise awareness at every level of the community, using different methods that speak to people’s realities.”

Gender apartheid: A systematic erasure

The women of Afghanistan have long navigated a deeply patriarchal society. But even in the face of repression, they have consistently resisted, even during the first Taliban regime, which imposed a system of gender apartheid that barred them from education, employment, and public life. After the Taliban was overthrown in 2001, their continued advocacy led to fragile legal and constitutional protections, enabling access to schools, workplaces, and political participation. With the Taliban’s return, those hard-won gains have been dismantled. Today, women in Afghanistan are being systematically erased—excluded from public spaces, denied legal recognition, and stripped of institutional protections. This deliberate exclusion reflects gender apartheid: an institutionalized regime of systematic oppression and domination of one group or groups over another aimed at maintaining control.

Similarly, under South Africa’s apartheid, Black, Indian, and Colored women faced compounded oppression. “Apartheid deliberately excluded us from political, economic, and social life. Black women, especially, were made invisible,” says Fester. Black South Africans were forcibly removed from participation in all spheres of public life. Black women were doubly marginalized, only permitted to reside in urban areas if registered as wives of legally entitled men.

Like the South African apartheid regime, the Taliban’s system of gender apartheid uses economic, legal, cultural, and social levers to normalize exclusion. “It’s the daily small things that entrench oppression. Over time, these become invisible, accepted as normal,” Fester explains. Mubarez highlights a parallel in Afghanistan: “Women do the hard work—in agriculture, livestock—but they don’t see the benefit. The money goes to the men. This keeps them dependent and powerless.”

Guerrilla education and resisting indoctrination

Oppressive regimes fear education because it fosters critical consciousness. In apartheid South Africa, the Bantu Education Act deliberately undereducated Black children. Women responded by creating “guerrilla schools” in homes and churches, teaching history, politics, liberation ideals, and critical thinking. “Education is not just about literacy. It’s about developing awareness, questioning injustice, and building the courage to resist,” says Fester.

The women of Afghanistan are employing similar tactics. Despite Taliban bans, underground schools and digital learning persist. But education must go beyond literacy, fostering critical thinking and reinforcing that education, work, and agency are fundamental rights—not Western imports.

Vocational training, while valuable, can reinforce traditional gender roles if not paired with rights education. “If we only teach women embroidery and sewing, we limit them. Women are capable of so much more,” Mubarez emphasizes. Empowering women through knowledge ensures that even vocational skills become a pathway to independence, not containment.

Intersectionality and the need for unity

Apartheid South Africa institutionalized division through rigid racial categories. “Apartheid deliberately divided people—Black, Colored, Indian—to prevent unity. It was a divide-and-rule strategy to keep us weak,” says Fester. Black South Africans faced the harshest oppression, but all groups were pitted against each other to fracture resistance. These divisions were compounded by intersecting harms and inequalities—economic marginalization, gender-based discrimination, and geographic segregation—that shaped how apartheid was experienced across different communities, deepening exclusion and reinforcing systemic control.

South African women recognized that fragmentation only served the regime. The United Democratic Front brought together Black, Colored, and Indian people, along with white allies. “We realized unity was our strength. We built alliances across race and class to fight a system that wanted us divided,” Fester reflects.

That unity, she recalls, was built over years of organizing and strategic alliances, beginning with the revival of the United Women’s Organisation in 1981. Despite apartheid’s rigid racial divisions, it brought together women from all legally defined racial groups to focus on education, empowerment, and women’s rights. While white women were privileged under apartheid, they too faced patriarchy. In 1983, women’s groups joined with men’s and youth organizations, trade unions, religious bodies, and cultural groups to form the United Democratic Front, uniting diverse communities in a shared struggle. By 1992, these strategic alliances expanded into the Women’s National Coalition, an organization with many differences but united by one goal: securing women’s and human rights in South Africa’s new constitution. To achieve this, they conducted nationwide consultations in rural farms, cities, religious institutions, and unions, gathering women’s demands into the Women’s Charter to present to political leaders in the negotiations.

Afghanistan faces similar divisions. The Taliban’s gender apartheid intersects with ethnic, sectarian, and geographic discrimination, further marginalizing groups such as the Hazaras, who are targeted for both their gender and ethnic identities.

Mubarez stresses the need for tailored engagement: “In rural areas, mullahs and elders have more sway than an educated person with a PhD. The community accepts their speech more. We should tactically use these figures to raise awareness before introducing ideas of gender justice.” She adds, “Different levels of the community need different methodologies. What works in universities or cities won’t work in villages.”

Fester notes that unity requires strategic alliance-building: “Men are not the enemy—it’s patriarchy and negative interpretations of religion that oppress women. We must find allies.”

The path forward: Resilience, strategy, and solidarity

South Africa’s anti-apartheid movement showed that sustained, strategic resistance can dismantle entrenched systems. “We had to be smart. We worked on issues that mattered to people—like water access or bread prices—and through these, we built a political movement,” Fester explains.

Mubarez links economic independence directly to addressing gender-based violence: “This mentality that the man has the right to control all the money keeps women dependent. This financial problem is also a root cause of domestic violence and forced marriages.”

Women in Afghanistan are already resisting—through underground schools, economic initiatives, and digital activism. Their demands are clear: Naan, Kaar, Azadi (Bread, Work, Freedom).

But they cannot succeed alone. Global solidarity was critical to dismantling South African apartheid. The women of Afghanistan deserve the same commitment. Every day under Taliban rule is a day too many. The women of Afghanistan will reclaim their rights—not as victims, but as leaders of their own liberation. The question is whether the world will stand with them or allow gender apartheid to continue unchecked.

Farhat Ariana Azami is a social worker and advocate for the rights of women and girls, as well as refugees. She serves as president of the Solidarity Group, an Austria-based association that provides homeschooling for girls and develops sustainable livelihood projects for women in Afghanistan.

This article is part of the Inside the Taliban’s Gender Apartheid series, a joint project of the Civic Engagement Project and the Atlantic Council’s Strategic Litigation Project.

Further reading

Wed, Jul 9, 2025

Five questions (and expert answers) about the ICC arrest warrants against Taliban leaders for crimes against women and girls

New Atlanticist By

Our international law experts unpack the implications of the International Criminal Court’s arrest warrants against the Taliban’s supreme leader and chief justice.

Wed, Jul 2, 2025

How centering Afghan women and youth now can help challenge oppressive regimes in the future

Inside the Taliban's gender apartheid By

Empowered Afghan youth and women embody a future vision for the country rooted in rights, participation, and accountability.

Thu, May 29, 2025

How the Taliban is using law for gender apartheid, and how to push back

New Atlanticist By

To combat the Taliban’s institutionalization of gender apartheid, international actors must document the system of lawmaking that underpins the regime's human rights abuses.

Image: Members of hte anti-apartheid Federation of Transvaal Women hold a placard demonstration outside the Chamber of MInes building protesting their silence of the govt.'s effective banning of 17 organizations. March 8, 1988 REUTERS/Wendy Schwegmann