Amid the grating cries of today’s agents of darkness, who propagate the fascist slogan “you are either with us or against us,” who serve our “sultan,” and not surprisingly buy into the deal of “obedience to the government for protection and profits;” amid the voices that justify injustices and violations of human rights and freedoms, and the economic and financial elite who perpetually seek to protect their privileges by supporting the autocrat and the close alliance between the government and the revolution; amid of all these, are the writers, politicians, and media figures who perpetuate myths to justify abandoning democracy and the continued dominion of the military establishment and security apparatus over state and society via the exceptional status granted them by the constitution, by their huge unregulated role in politics and economics, and by the presidential candidacy of the former defense minister.

Amid the grating cries of today’s agents of darkness, who propagate the fascist slogan “you are either with us or against us,” who serve our “sultan,” and not surprisingly buy into the deal of “obedience to the government for protection and profits;” amid the voices that justify injustices and violations of human rights and freedoms, and the economic and financial elite who perpetually seek to protect their privileges by supporting the autocrat and the close alliance between the government and the revolution; amid of all these, are the writers, politicians, and media figures who perpetuate myths to justify abandoning democracy and the continued dominion of the military establishment and security apparatus over state and society via the exceptional status granted them by the constitution, by their huge unregulated role in politics and economics, and by the presidential candidacy of the former defense minister.

I previously discussed the “candidate of necessity” myth, and today I will discuss the myth of neo-Nasserism, systematically analyzing and debunking its many components, its diverse contexts, and how it has been used to justify authoritarianism.

The first component of the myth of neo-Nasserism is its idealistic and romantic recollection of the 1950s and 60s, and its depiction of those decades to the public as an extended era of national independence, rejection of domination by other countries, economic prosperity, and social modernization, with social justice policies that defended the poor, under the leadership of the military establishment and a single, heroic military leader, commander, and savior. On one hand, this idealistic and romantic recollection of the 50s and 60s downplays the catastrophic breaches of human rights and freedoms, which are falsely described as either necessary for national independence and social justice or as mere errors that could have been avoided. On the other hand, there is a dearth of critical evaluation of Nasserism, which was founded on autocracy, the military establishment’s intervention in politics, and the predominance of the intelligence and security agencies. Nasserism weakened the state’s administrative institutions, which became iron cages of bureaucracy that lacked efficiency and bred routine, corruption, and nepotism. It crippled the rate of economic growth and the mechanisms of sustainable social modernization, most notably higher education, large- and small-scale investment in scientific research, the democratic partnership between the state and public activity, and the independent role of the private sector. It also cost Egypt a catastrophic military defeat in 1967. The idealistic and romantic recollection of the 50s and 60s dresses up the idea of autocracy in the false robes of the “just dictator.” It justifies the military establishment’s intervention in politics and the predominance of the intelligence and security agencies as the direct results of the weakness of the civil, political, and economic elite and of the necessities of national security and preserving the cohesion of the nation-state. It blames local or foreign conspiracies or “the avoidable mistakes of Nasserism,” like the breaches of rights and freedoms, for the lack of growth and modernization and the catastrophic military defeat. The truth that this idealistic and romantic recollection denies in 2014 is that all of the dangerous violations and breaches mentioned above were the inevitable result of the autocracy established in the 50s and 60s. After all, in the 20th century that autocracy inevitably thwarted the very goals it had promised its droves of crushed and broken citizens. In the end, it did nothing to preserve national independence, to promote development and modernization, to create a country with strong institutions that abide by the constitution, the rule of law, or the standards of efficiency and fairness, or to foster a productive and educated society that ensures citizens’ economic, social, and political rights.

The second element of the neo-Nasserism myth is connected to a claim that is contradicted by Egyptian history from the 1950s until the January 2011 revolution. In essence, it is that the arrival of former President Anwar Sadat to office in 1970 made a break from the Nasserist period, which only grew during the three decades under former President Hosni Mubarak. On the one hand, this creates a distinction between Nasserism – which strove for national independence, development, modernization, and social justice, and was biased towards the poor and low-income – and the governments of Sadat and Mubarak – who pushed Egypt towards subordination to other countries, ignored development and modernization, and turned against the poor and low-income in favor of an alliance between the government and the revolution, and of a corrupt and exploitative economy. On the other, it offers the public reductionist explanations for this distinction that revolve around the “correct” choices of the heroic military savior and the “incorrect” choices of the presidents who came after him, as well as the central role of the military establishment and nation’s public sector in the 50s and 60s and its subsequent regression in favor of the “civilian,” economic, financial, and security elite in the 70s. But this claim of a complete break between Nasserism and the eras of Sadat and Mubarak denies the objective truth that the role of the military in the state, society, and politics has not decreased since the 50s. Rather, the overlap between the military and civilian elite has grown for reasons concerning the interests of the government and the revolution. Furthermore, none of the economic or social policies towards the public sector or in support of the poor and low-income have changed; the state institutions have only become less capable of effectively implementing them, after years of corruption, nepotism, and administrative exploitation of society’s resources. The predominance of the intelligence and security agencies has not changed since the 1950s, and neither have the breaches of rights and freedoms. National independence took a hard hit in 1967, and though the Egyptian administration (and the military-civilian collaboration) reclaimed its land after the 1973 victory, the government surrendered to Western subordination and largely relinquished its national and pan-Arab role. It is absolutely impossible to argue that Nasser’s decisions were “correct” while the decisions of his successors were “incorrect.” Some of their decisions were essentially the same, such as the oppression, restrictions on freedoms, and the practices of the state security apparatus. Others began under Nasser and continued under his successors. These included the tyranny of bureaucracy and the inefficiency of state institutions and executive and administrative agencies. They also included the domination of the “trusted” elites (military and civilian) over their knowledgeable, intellectual, thoughtful, and experienced counterparts to the degree of producing corruption, nepotism, and laziness. A last category, however, did differ, whether partially – as in the case of the presidents’ economic models, social attitudes, and weight of the public and private sectors – or completely – as in the case of their regional and international policies. Egypt has yet to completely break away from Nasserism and its disastrous consequences, including militarization, the absence of democracy, and a crippling lack of development.

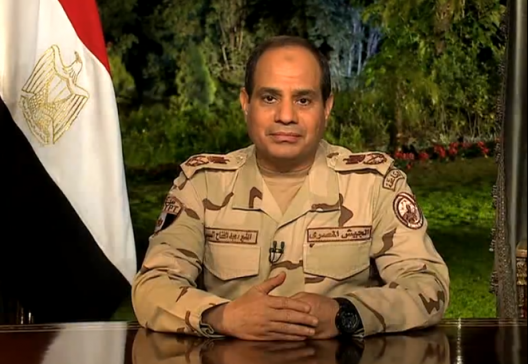

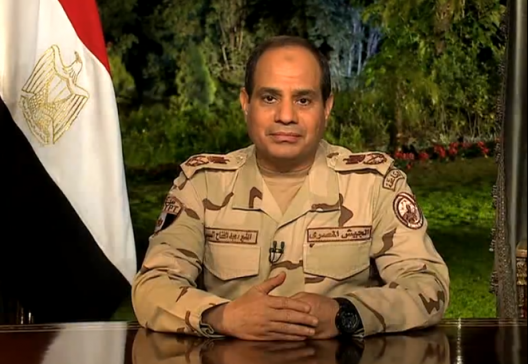

The third element of the neo-Nasserism myth relies on people’s false perception that reproducing the attitudes and policies of the 50s and 60s is the way out of our current failures and crises, and that “the candidate of necessity” in the presidential election, Former Defense Minister Abdel Fattah al-Sisi, is the only person capable of moving Egypt in that direction. The writers, politicians, and media figures involved in perpetuating the myth of neo-Nasserism differ in their explanations for the current crises and failures. Some believe they are connected to the weakness of the nation state and the weakened capacities of its institutions and agencies. Others treat the crises as synonymous with the absence of development and social justice. A third group believes that they are the result of the corruption of the political elite and the wickedness of the economic and financial elite. A final group blames them on local and foreign conspiracies, which plague Egypt and threaten it sovereignty, national security, and civil peace.

They trick people by suggesting that reproducing Nasserism would be a way out of all these failures and crises, while they know that the fruits of the 50s and 60s were far from sweet. They suggest that government intervention in the revolution would lead to development and social justice, while they do not fight corruption or reign in the wicked economic and financial elite. They suggest that the economic and political climate of the region in the 50s and 60s was fundamentally different from today. Nevertheless, no economic attitude based on “import substitution industrialization” seems feasible, and conflict with the reactionary Arab monarchies has led to alliances and an increased financial dependency on the Gulf. Searching for a relatively independent position towards the Western and Eastern camps and a way to benefit from their conflicts is even less complicated than navigating the spider webs of world interests and the dogfights of the world powers, who show few essential differences – from the Democratic West to the capitalist Chinese and Russian East – as they all strive to subordinate small and mid-size nations. They trick people by claiming that only a heroic savior from the military establishment is capable of protecting the nation state, fostering development and social justice, and frustrating local and foreign conspiracies. It is as if the nation state is the priority of the military and no one else, and that, in the minds of civilians, development and social justice are mere luxuries. It is as if the military and their allies in the intelligence and security agencies held a monopoly on fighting both local and foreign conspiracies. It is as if the autocracy connected since the 50s and 60s to presidents with military backgrounds had not weakened the nation state with its absence of democracy, the rule of law, justice, and freedom, and had not derailed development and social justice for the benefit, profit, and gain of the ruling military-security sector and the wicked economic and financial elite. It is as if fighting those local and foreign conspiracies was conditioned on abandoning the need to build a democratic nation state, society, social justice, and a legitimate government that adheres to the rule of law and the principles of transparency and fairness. After all, these are all ideas that autocracy throws to the wind.

The fourth element of the myth of neo-Nasserism is the direct relationship between the heroic savior with a military background and the common people, who have no need for political entities, parties, or civil society organizations as mediators, or for legal or popular monitoring of the government. They are beyond such limitations due to their hero’s deep love for the public and their limitless trust in him; they identify with their hero, who has been chosen by fate. This component offers the public a simple approach to governance, power, and politics. In this approach, politics is essentially dead and the government thrusts its hand deep into the state and society without supervision or control. Autocracy is justified and allowed to monopolize the discourse in the name of the public and the masses – while the individual citizen is crushed – and to make claims that it is impartial, pure, and the embodiment of their hopes and dreams. A few of the false statements that came from the Nasserist period, for instance, include that political parties were forums for private, special interests, or that all different types of civil society organizations were under the control of foreign powers which determined their priorities and activities, or that the tools and mechanisms of popular and legal monitoring of the government remained ineffective as long as the ruler himself did not endorse them. As with Abdel Nasser, a rose-tinted picture of a heroic military savior has been painted in the public imagination. In 2014, that savior is capable of transcending party limitations, gaining control of the foreign-influenced civil society, and transparently communicating with the public and the masses. What allows him to do so is his ability to monitor and hold others accountable. This rose-tinted picture goes hand in hand with the sales pitch that the military establishment is the only institution that can stop the political entities and parties toying with the nation and quarantine the damage caused by civil society organizations, which it accuses of working against the nation state to fragment society. Then, in the name of the direct relationship between the heroic savior and the public (the connections of love and trust) and in the name of the military’s necessary role, it justifies autocracy, militarization, the absence of democracy, the oppression of civil society, the disappearance of the individual citizen, and the weakness of legislative, executive, and judicial institutions and agencies meant to monitor the ruler and hold him accountable.

The story is the same as that of the candidate of necessity in the presidential elections. The myth of neo-Nasserism, with its many components and diverse contexts, has one goal: to justify autocracy and convince the public that it must inevitably accept the dominion of the military establishment over the state and society, and support its heroic savior. It does so in spite of the bitter fruits of the Nasserist period in the 50s and 60s, the fundamental difference in the situation today, the tragedy of romanticizing the past, the disastrous reduction of the nation to one ruler who is neither monitored nor held accountable, the danger of allowing the government and the wicked economic and financial elite allied with it to gain more power, and the delusion that those who oppose the government are abandoning the defense of the nation or following foreign agendas.

Amr Hamzawy joined the Department of Public Policy and Administration at the American University in Cairo in 2011, where he continues to serve today. He is a former member of parliament, former member of the National Salvation Front, and founder of the Freedom Egypt Party.

This article originally appeared in Shorouk