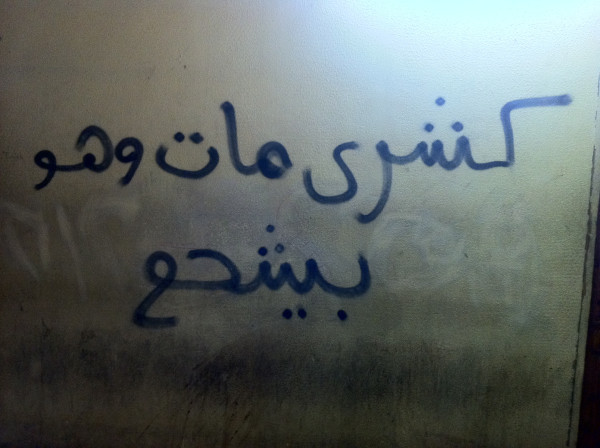

"My friend died while cheering"read the graffiti on the wall inside a Cairo metro station, a reference to deadly rioting at a soccer stadium in Port Said on February 1 that killed nearly two hundred spectators. Although Egypt’s transition has been troubled by persistent violence, protests, and economic instability, the bloody incident at Port Said exceeded everyone’s worst expectations: No one saw it coming. Today, the official death toll of 194 is still rising. In the days since, activists and parliamentarians alike have leveled harsh accusations at the interim government, accusing the Interior Ministry and remnants of the former regime of deliberately facilitating the rioting by failing to properly secure the stadium and refusing to intervene when violence erupted.

The fact that the main victims of the violence were Ultras — hardcore soccer fans who played an integral part in mobilizing anti-government protests at the start of the revolution last year – is another indicator of the government’s sinister intentions. The Ultras strong organizational tactics and decentralized strategy allowed them to effectively organize marches and evade security forces during the first wave of the revolution. During the infamous Battle of the Camel, for example, Ultras fought shoulder-to-shoulder with the revolutionaries, defending and rescuing civilians in Tahrir Square from a brutal assault be regime-organized thugs. Even after protesters left Tahrir Square, the Ultras remained politically active: In the soccer stadiums, they performed choreographed cheers and dramatic entrances honoring the victims of the revolution continuing to call for the realization of their unfulfilled demands.

The Ultras had never intended to get into politics; in fact it has been one of their taboos along with religion, but like all Egyptian they had experienced their fair share of harassment by security forces prior to the revolution, which galvanized their opposition to the Interior Ministry and Mubarak regime. The fanaticism and the violence they have displayed at past soccer matches are undeniable and inexcusable. However, their behavior can to a large extent be traced to the systematic repression they suffered at the hands of the Interior Ministry.

Soccer in Egypt has always been more than a sport, and like all social phenomena – the game was manipulated by the Mubarak regime to advance its own political interests and undercut the opposition. The regime was always keen on maintaining close ties with the most popular players, who made frequent media appearances endorsing the president and his government. Before the revolution, the word "Patriotism" word was ubiquitous in official publications and propaganda related to international soccer competitions. I have a vivid memory of Alaa Mubarak’s post-game commentary one of the most popular sports shows after the fierce competitive Egypt-Algeria World Cup game in 2009 sparked violent clashes between rival fans at the stadium in Cairo. The former president’s son did nothing to diffuse the tensions when he said, "We respect our brothers in the Gulf and we have never had problems with them, but apparently the Algerians envy us and we all felt [the consequences].” This irresponsible and provocative statement by a major public figure not only inflamed international rivalry with Algeria but left a painful stain on Egypt’s soccer legacy and was a reminder of the deep political and nationalist undercurrents associated with the national sport.

Looking back at the Port Said violence in retrospect, the blame clearly lies not with individual perpetrators of violence, but with a structural failure of security and public safety measures that could only have occurred with the knowing complicity of government officials. Mohamed Gamal Besheer, a sports activist who has published on Egypt’s Ultras, believes that the violence in Port Said went far beyond the normal friction observed at past games between the rival al-Ahly and al-Masry teams. Certain conspicuous irregularities at this particular game — the welded gates, lighting blackout, and the idle passivity of policemen who stood around taking pictures of the violence on their cell phones instead of intervening to restrain the crowds – are all clear signs indicating that elements of the security apparatus loyal to the former regime deliberately set the stage for an unsafe, highly congested and volatile scenario that was guaranteed to result in panic and violence. Recently, al-Badry Fargahly, the MP representing Port Said, stated that a prominent businessman and one of Gamal Mubarak’s close friends is involved in instigating the incident. On the other hand, the parliamentary fact-finding committee’s preliminary report amounted to little more than a slap on the wrist for the Interior Minsitry: The report only blamed the ministry for failing to learn from the past violent confrontations that had taken place between the al-Masry fans andfans from different clubs (Inpi, Ismaili, Etehad) through the past period and for not being well prepared for such a big game. It also blamed Sports analysts and sports channels for provoking fanaticism and and escalating the rivalry between the fans of both clubs in the aftermath of the events.

Rather than accept responsibility for the security breakdown, government officials and leaders of the national football association have shameless tried to deflect blame for the violence onto residents of Port Said, attempting to portray them as characteristically violent and reckless. Although the head of the Egyptian Football Union resigned over the incident, he stated publicly after the fact that he only stepped down as a face-saving gesture to protect the government from criticism, and insisted that he will never face trial for the violence and bloodshed that occurred on his watch.

Egyptians who were still willing to give the SCAF and interim government the benefit of the doubt before the violence in Port Said are now losing faith in public officials and recognizing that the government failed catastrophically in its responsibility to maintain public safety. The statement of Field Marshal Tantawi in the aftermath of the incident, in which he urged Egyptians to "face the people who did this" confirms the interim government’s unwillingness to accept culpability. One has to wonder whether Tantawi was simply caught off guard when he made these ill-considered remarks, or if he really believes this? If the latter, the stage is set for a major confrontation between the military and a public that it has betrayed.

The greatest danger now is that the energy of the Egyptian people will be diverted to specific grievances and distract attention from the fundamental problem: a lack of accountability for government officials accused of crimes against the people. Protesting individual incidents while losing focus on the root causes of the current injustice is like treating a fatal illness with aspirin, allowing the perpetrators to walk away unpunished.

Sara Ashour is an Egyptian freelance researcher. She is currently pursuing a master’s degree in comparative political systems at Cairo University.

Photo Credit: Twitter / Translation: "My friend died while cheering"

Image: My%20Friend%20Died%20While%20Cheering.jpg