Ambassador Brett McGurk, the deputy to anti-Islamic State (anti-ISIS or -ISIL) coalition coordinator General John Allen, told the House Foreign Affairs Committee on December 10, “We do not see a situation in which the [nationalist] rebels are able to remove Assad from power … It will have to be a diplomatic process.” This was, in part, a cold-blooded diagnosis reflecting the results of an administration policy calling on a brutal dictator to step aside while providing scant support to those who would push him. It was, in part, a prescription for diplomacy. But what diplomatic process? How is it to materialize? When is it to appear? What is the administration actually saying to Syrian nationalists about the course of treatment it proposes?

Ambassador Brett McGurk, the deputy to anti-Islamic State (anti-ISIS or -ISIL) coalition coordinator General John Allen, told the House Foreign Affairs Committee on December 10, “We do not see a situation in which the [nationalist] rebels are able to remove Assad from power … It will have to be a diplomatic process.” This was, in part, a cold-blooded diagnosis reflecting the results of an administration policy calling on a brutal dictator to step aside while providing scant support to those who would push him. It was, in part, a prescription for diplomacy. But what diplomatic process? How is it to materialize? When is it to appear? What is the administration actually saying to Syrian nationalists about the course of treatment it proposes?

Indeed, the administration is trying to persuade nationalist Syrian opponents of the Assad regime to sign up to be trained and equipped to help the United States defeat ISIL. These prospective recruits—and the populations from which they are drawn—have been assaulted for nearly four years relentlessly by a ruling family for which no crime has been unthinkable. They continue to absorb the horrors of barrel bombing, artillery shelling, starvation sieges, torture, and sexual abuse at the hands of a family content to sacrifice the lives of fellow Alawites in its defense while it plays tennis and counts money. How are nationalist victims to process Dr. McGurk’s sober diagnosis and suggested prescription? Their reaction is important. Washington says it needs them.

Syrian opposition leaders and nationalist fighters profess to be clueless about US intentions. Is this remotely possible? Is no one in the administration consulting the leaders of the Syrian National Coalition: the organization recognized in December 2012 by Washington as the legitimate representative of the Syrian people? Surely, for an endeavor of this importance there must be a Syrian interlocutor. After all, a diplomatic process begins with diplomacy. Diplomacy begins with securing the support of partners, even those who do not rise to perfection.

Yet the opposition says it is being ignored. Worse, it claims that Washington is uninterested in receiving tactical intelligence from nationalist rebels fighting ISIL in Syria. Suspicions in opposition circles are rife. Is Washington loath to accept targeting intelligence for fear that it would imply an obligation to help the providers? Is the White House—notwithstanding President Obama’s Brisbane description of Bashar al-Assad as a murderer—under the influence of Assad sympathizers and apologists? For Americans, these things are unthinkable: they smack of conspiracy mongering. For Syrians in desperate straits who see their nemesis—Assad—taking full advantage of the US-led anti-ISIL air campaign, Washington’s motives seem suspect at best.

All of this angers the White House. The supposed unfairness and ingratitude of the Syrian opposition—the feckless, dysfunctional, and divided opposition, don’t you know—seems to raise blood pressure and inspire invective in ways that mass murder does not. Historians will parse at their leisure if and why this was so. Leisure, however, is not a luxury for millions of Syrians deemed ineligible for help under the “Never Again” rubric. If their salvation is to be in the form of a diplomatic process, perhaps the administration might deign to explain what it has in mind.

For the Assad regime’s key supporters—Iran and Russia—the pivotal role of the regime in birthing ISIL, attracting foreign fighters, and wrecking Syria are all well known. Yet for Tehran and Moscow, the regime has important uses. Iran has a junior partner who will do whatever Tehran wants to help Hezbollah keep its rockets and missiles trained on Israel and ready to fire. A less noxious replacement for such a reliable subordinate would be hard to find; he may not exist. As for Moscow, Assad is the poster child for stopping cold what it—and it alone—sees as Barack Obama’s mania for violent worldwide regime change. When Vladimir Putin casts his gaze upon a cynical kleptocrat claiming to be an anti-terror champion, what’s not to like?

For much of 2013, Washington hoped that Moscow would induce a militarily secure Assad to negotiate his own transition to retirement. Yet even if Russia wanted to do such a thing (which it did not) it lacked the leverage to make it happen. The result was 2014 opening with a Geneva conference fiasco. What will be the theme of 2015’s wishing and hoping? That Iran will divest itself of a strategic asset? Why would it do so, especially when it thinks Washington craves a nuclear deal above all else? Indeed, the administration has not denied reports of a presidential letter to the Supreme Leader assuring him that Assad is not a target of US military intervention in Syria. If true, how would a voluntary assurance of this nature enable successful diplomacy?

The fear here is that the prescription—a diplomatic process—is a place-holding placebo. When one elects not to meaningfully support those who could have put Assad back on heels while preventing ISIL from seizing eastern Syria; when one covers the consequences of such a decision by chanting the mantra of no military solution for Syria; when one looks the other way while Iran and Russia create a military solution to their liking; when one announces, with clinical disinterest, that lo and behold the nationalist opposition will not defeat Assad; when all of this is decided and pronounced, what is left to say beyond, in effect, “This unseemly Assad mess ought to be resolved diplomatically. After all, there is no military solution. So let us fight ISIL—for which there is a military solution—and perhaps something on Assad will turn up. Sorry about the slaughter. We’ll send the United Nations another check.”

If this is what is meant when administration officials speak of a diplomatic process, then avoiding Syrians and wishing they would shut up is understandable. Trying to recruit to our fight against ISIL those whose life and death priorities are consigned by us to never-never land is not so understandable, even in an “it’s all about us” context.

Closing this widening gap between strategy and policy ought to keep the White House too busy to be angry with civilized Syrian critics. It would be far better in any event to be criticized—pilloried, if possible—by a mass murderer. President Obama says he wants an Assad-free political transition for Syria. Syrians he wants to recruit to fight ISIL want to know how he will help them set the conditions for the Assad-free outcome he says he wants. Prescribing a placebo will not do the job. And it will attract no one to the battle against ISIL.

Frederic C. Hof is a resident senior fellow with the Atlantic Council’s Rafik Hariri Center for the Middle East.

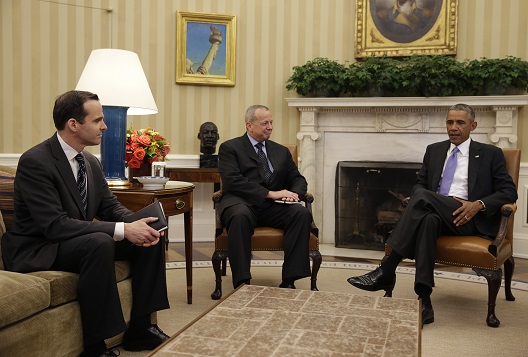

Image: President Barack Obama (R) meets with Special Presidential Envoy for the Global Coalition to counter the Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant (ISIL) United States Marine Corps (USMC) General John Allen (C) and Deputy Special Presidential Envoy Brett McGurk (L) in the Oval Office of the White House in Washington September 16, 2014. REUTERS/Gary Cameron