Over the past two years, Tunisia has been plagued by terrorist attacks, characterized by car bombs and targeted political assassinations. In the wake of increased terrorist threats, economic recovery—largely overshadowed by the electoral process—remains in jeopardy. With persistently weak demand for Tunisian exports to Europe, the government’s hesitation to undertake the structural reforms, and excessive wage and subsidies bills, the Tunisian economy still suffers a lack of robust growth.

Over the past two years, Tunisia has been plagued by terrorist attacks, characterized by car bombs and targeted political assassinations. In the wake of increased terrorist threats, economic recovery—largely overshadowed by the electoral process—remains in jeopardy. With persistently weak demand for Tunisian exports to Europe, the government’s hesitation to undertake the structural reforms, and excessive wage and subsidies bills, the Tunisian economy still suffers a lack of robust growth.

The Tunisian economy is particularly sensitive to security threats. Unlike its North African neighbor Algeria, which experienced terrorist threats throughout the 1990s, Tunisia does not have oil and gas revenue or large sums of foreign exchange reserves to shield the economy from exogenous shocks. The country is in dire need of developing its up-market products to improve qualitative or non-price competitiveness. This edge could limit the Tunisian economy’s vulnerability to the instability of tourism receipts and to put an end to the chronic current account deficit, which reached 5.3 percent during first half of 2014 (as compared to 4.4 percent during the same period in 2013).

Terrorism and Economy: The Transmission Channels

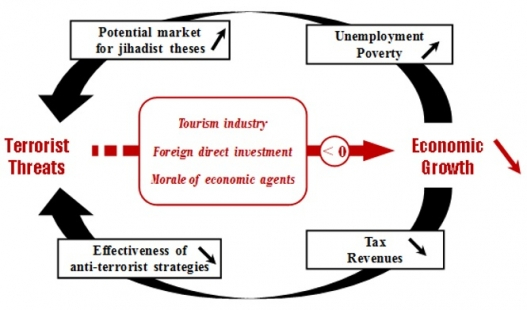

In a country plagued by macroeconomic instability and socioeconomic inequality, the imminent threat of terrorist incursions has taken a toll on growth. For a country already trapped in a very low growth rate, averaging 2-3 percent a year, security threats pose too great an economic consequence that the country cannot afford during this phase of its transition. Security threats, specifically terrorism attacks, may impair Tunisia’s the main transmission channels: tourism, foreign direct investment (FDI), and social spending [Figure 1].

The tourism sector faces the highest risk of negative impact from terrorist threats. First, the rise in terrorism often causes a drop in tourist bookings, which consequently leads to the drop in tourism revenues, known as the income effect. As a pillar of the Tunisian economy, tourism contributes directly to social development and provides a source of foreign currency. Tourism revenues cover more than 50 percent of the country’s trade deficit and employs 12 percent of the labor force, largely contributing to economic prosperity.

The insecurity generated by the terrorist acts increases the risk of stifling innovation in the tourism sector and the widespread use of all-inclusive travel packages. As a result, other supporting sectors, like food and beverage, transportation, crafts, and archaeological sites will not profit from the benefits of tourist arrivals. Known as the quality effect,its negative impact could destabilize the sector further, not to mention other macroeconomic knock-on effects.

In terms of investment, FDI flows are closely linked to terrorist acts. First, terrorism—or any security-related instability—raises the cost of doing business (primarily due to expensive security measures) and reduces the return on FDI. The increased costs, as a direct impact of weak security, drives the outflow and reduction of FDI as risk-averse investors decide against participating in an insecure market. The latest figures published by Tunisian authorities show a sharp decline in foreign investment inflows recorded in the first half of 2014, a fall of 26.2 percent compared to the same period of 2013.

Second, the decline in FDI negatively affects foreign exchange reserves, threatening the Central Bank of Tunisia’s ability to meet market demand for foreign currency. A shortfall in foreign currency liquidity puts direct downward pressure on the Tunisian dinar to depreciate with respect to the US dollar and the Euro. The increased “country risk” from the terrorist threat sends insurance premiums soaring. In the past three years, the top three rating agencies have downgraded Tunisia, citing the rise in terrorist attacks and political instability: Moody’s cut Tunisia’s sovereign rating to Ba3 from Baa3, Fitch cut it from BBB- to BB-, and Standard & Poor’s lowered it from BB to B. The downgrades have resulted in a net decline in FDI and a net increase in prices of imported goods, which could feed into inflationary pressures and lead investors and consumers to delay their purchasing decisions.

Third, terrorism directly affects government expenditure on more productive social programs—such as education, infrastructure, and social welfare—as it diverts funds to maintaining security. The effect on growth creates a feed-forward cycle that could in fact contribute to insecurity and weak economic growth. As government investment declines, slow growth leads to rising unemployment and poverty. As social needs approach desperation, so too does the inclination to turn to violence [Figure 1]. Slow growth also results in a decline in tax revenues, which further prohibits government spending on advanced equipment to fight terrorist groups, and so on.

Overall, the rise in terrorism could weaken the morale of the main economic agents (consumer and investor), and contribute to the deterioration of the business climate. Terrorist attacks generate uncertainty and promote all forms of speculative behavior, leading investors and households to postpone their long-term projects. The lack of electoral transparency and the delay of the New Investment Code has already frozen Tunisian investors in a wait-and-see attitude, feeding the decline in domestic investment and economic growth. Consumers would feel similar pressures, particularly regarding purchases of durable goods and real estate.

Options for exit strategies

To reverse this destructive trend in Tunisia, the government must consider a number of measures on both the economic and security fronts. Among them, border security is an imperative to prevent the movement of militants and arms into and out of the country. To monitor the border effectively, Tunisia’s military needs modern equipment, such as helicopters or surveillance aircraft, a sophisticated control system for the airport, improved monitoring systems for the ports, and border inspection posts. Such equipment would also have dual use purposes in improving the effectiveness of anti-terrorism operations in Tunisia’s interior.

Border security would also tackle the effects of a parallel black-market economy. Cross-border trafficking, smuggling, and other criminal activity not only leads to increased insecurity, it also draws labor away from the formal economy and produces stress on production and growth. Terrorists groups also benefit from the flourishing of an economy outside the law (estimated at around 40 percent of GDP) to finance their operations.

As the Tunisian National Constitutional Assembly debates draft counterterrorism legislation, it must also consider the tradeoff between freedom and security. Police need the appropriate leeway to investigate and apprehend terrorist suspects while exercising restraint and maintaining the public trust. Restrictions on freedom, if taken too far, could result in political instability, which in turn could negatively affect economic growth.

Lastly, Tunisia must coordinate with international partners. The quality and efficacy of domestic policy against terrorism remains dependent on the willingness of Tunisian authorities to coordinate, not only with its Libyan and Algerian neighbors, but also with its US and European partners. With support from the Algerian army and the assistance package from the United States promised to Tunisian President Moncef Marzouki during his visit to United States in August 2014, Tunisia could maintain an effective environment to counter terrorism.

On the economic front, the government must prioritize tax and subsidy reform to reduce the fiscal deficit and mobilize the necessary finances to mitigate the economic factors that lead toward terrorism. Education reform could also help institutionalize a culture of tolerance and help students adapt to the requirements of the working environment. Such reform would lead to a drop in unemployment, which may limit the potential pool of terrorist recruits.

Between improved security and growth-driven economic policies, the Tunisian government could effectively counter the terrorist threat—a long-term strategy that the government can ill-afford to postpone.

Moez Labidi is a Tunisian economist and a nonresident fellow with the Atlantic Council’s Rafik Hariri Center for the Middle East.

Image: Tunisia's Prime Minister Mehdi Jomaa (R) speaks with his French counterpart Manuel Valls during "Invest in Tunisia, Start-up Democracy" international conference in Tunis September 8, 2014. (Photo: REUTERS/Zoubeir Souissi)