On the first day of the Al-Jazeera trial, the prosecutor read the names of twenty defendants. It included three journalists, Mohamed Fahmy, Peter Greste and Baher Mohamed, as well as three college students, Khaled Abdelraouf, Suhaib Saad, and Shadi Abdelhamid. According to all six defendants, the first time they met was behind the bars of the defendants’ cage.

On the first day of the Al-Jazeera trial, the prosecutor read the names of twenty defendants. It included three journalists, Mohamed Fahmy, Peter Greste and Baher Mohamed, as well as three college students, Khaled Abdelraouf, Suhaib Saad, and Shadi Abdelhamid. According to all six defendants, the first time they met was behind the bars of the defendants’ cage.

It was also the first time Fahmy learned of the charges the prosecution was bringing against him: forming and running a Muslim Brotherhood media network. The prosecutor referred to Mohamed Fahmy as “a member of the terrorist Muslim Brotherhood organization responsible for establishing undercover media centers.” He accused Fahmy of directly overseeing the work of the three students, and other defendants, whom he also had not met prior to the trial.

In the almost year since their arrest, local and international coverage has focused mainly on the leading trio,and other foreign journalists tried in absentia. Few have looked into the identities of the other defendants,or the details of how they came to stand trial alongside Fahmy, Greste and Mohamed. The Al-Jazeera story itself announcing the verdict against its journalists makes no mention of the students.

With a deeper look into the details of these unknown faces, it appears that Egypt’s authorities used the students’affiliation with the Muslim Brotherhood to cement its claims that Al-Jazeera had sided with the organization. However, culpability is not for the Egyptian authorities alone. The complex details of the Al-Jazeera trial also show that the Qatari funded network had sunk into a political dispute with Egypt’s regime. The network’s editorial policies and on the ground tacticsrecklessly risked not only the wellbeing of their employees, but also shed major doubts on the credibility of the networks coverage of Egypt’s unstable political affairs.

Evidence showing the negligence of Al-Jazeera’s top officials, and the details of the incriminating testimony given by Al-Jazeera’s Egyptian producer Baher Mohamed, sentenced to ten years in prison, proved to be only two hidden aspects of the trial, while the story of three students who shared the cage with Al-Jazeera’s employees, reveal a third dimension.

Who Were the Three Students in the Al-Jazeera Trial?

On January 2, 2014, police in Cairo’s Moqattam district apprehended the three students at a checkpoint around 3 am. The arrest took place three days after Al-Jazeera’s Mohamed Fahmy and Peter Greste were apprehended from the Marriott Hotel in Cairo’s upscale Zamalek neighborhood, and Baher Mohamed from his home in western Cairo. The details of the students’ arrest were confirmed by their lawyer.

It was an unlucky moment for the three students, not only because Abdelraouf had been carrying a professional camera, a magnet for trouble at the time, or because they were on their way to an apartment registered as a media office, Al-Nour Media Production Company, but because Shadi was in possession of 15,000 Egyptian pounds. The money was meant for a lawyer defending his brother Ahmed, who was arrested days earlier with Anas al-Beltagy, the son of leading Muslim Brotherhood figure Mohamed al-Beltagy. They were both later added to the defendants list in the Al-Jazeera case.

The three were transported to the nearby Moqattam Police Station where their interrogation began. The next day, a police force took the students with them to raid the media company office that also served as their temporary residence. There, several computers, satellite broadcast equipment, satellite phones, and cameras were confiscated.

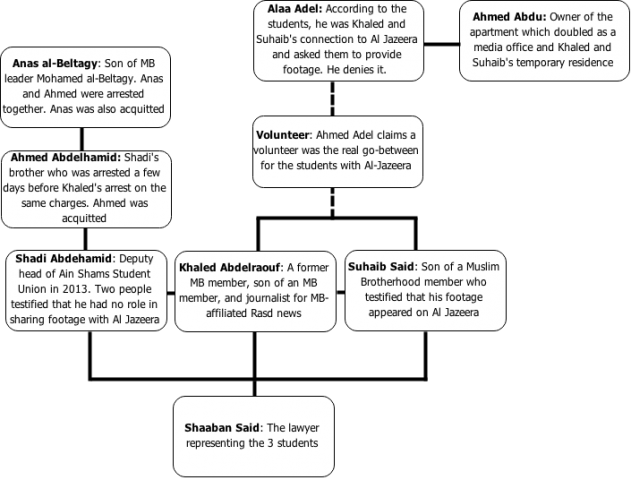

Abdelraouf, who was working with the Brotherhood affiliated Rasd News, told the prosecutor during his interrogation that he had been a member of the Muslim Brotherhood organization and worked at the Freedom and Justice Party’s media office, until he defected from the party in mid-2012. Abdelraouf explained that he had met a man named Alaa Adel through a mutual acquaintance during the pro-Morsi Raba’a al-Adaweya sit in. “Adel offered me a job at his newly established video production company,” he said.

Both Abdelraouf and Saad, whose fathers are members of the Muslim Brotherhood, told their interrogators Alaa Adel hosted them at the office of Al-Nour Media Production Company. He asked them to “film protests and upload the footage to his accounts on Bambuser and Ustream.” Adel said he would then sell their footage to different satellite channels.

They both added that Adel gave them filming equipment and varying amounts of money. During the interrogation, they claimed they only later learned that two of their films were aired on Al-Jazeera Mubashir Misr, the controversial channel that was banned by a court ruling in September 2013. During the trial, the prosecution would argue otherwise, however, without making mention of Adel’s name in court or adding him to the list of defendants, despite him being mentioned several times during the interrogation by the three students. Ahmed Abdu, the owner of their temporary residence that also hosted Al-Nour Media Production Company was listed as an absent defendant, but never appeared in court and was later sentenced to ten years in absentia.

The third student, Shadi Abdelhamid, who was elected deputy head of Ain Shams University’s Students Union in 2013, the second biggest in the country, told the prosecutor that he just happened to be with Abdelraouf and Saad on the night of their arrest. Abdelhamid’s statement was confirmed by the two others who testified that he was not sharing their temporary residence or involved in their independent filming work.

The common denominator between all three, probably to the liking of Egypt’s security authorities, is that they were actively sympathetic to the Muslim Brotherhood and had regularly participated in the organization’s protests since former president Mohamed Morsi’s ouster.

Tying the Students to Al-Jazeera

One of the first requests filed by the legal defense of Fahmy, Greste and Mohamed was the separation of Al-Jazeera’s employees from the rest of the defendants. This request was ignored, despite the fact that when the defendants were allowed to address the court, the students and the Al-Jazeera journalists confirmed they had never met.

Days later, the prosecution and court revealed why the request was never heeded. The evidence presented by the prosecution against Abdelraouf, Saad, and Abdelhamid included an audio track found on a cell phone confiscated during their initial arrest. The track was played in court and described in the 57-page verdict report.

According to the court document, two people named Shadi and Khaled could be heard speaking to someone about receiving cameras from Al-Jazeera as well as $300 each, in order to broadcast the activities of a Friday protest. They also referred to another eight cameras with live broadcasting capabilities, as well as an amount of $500 with each camera.

The document read, “Alaa, the person speaking to them, replied saying that he was among those who commandeered the satellite broadcast vehicle in Raba’a al-Adaweya [the pro-Morsi sit in] and that he owns thirty cameras given to him by Al-Jazeera and distributed across the country. He added that they seize any camera that films footage they don’t agree to air, and that they deal with Al-Jazeera network and not only Al-Jazeera Mubashir Misr.”

The court document went on to say, contrary to their original statements, that Khaled and Shadi wanted their footage delivered to Al-Jazeera, and that they asked for compensation in order to make flags and banners for the protests. It added that Alaa said, “Khaled knows the details better,” adding that “if anyone faces security issues he would be able to get them an entry visa to Qatar.

Throughout the trial, Abdelraouf, Saad, and Abdelhamid were represented by Shabaan Said, a prominent Cairo lawyer hired by the families of the three students. Said was also formerly hired by Al-Jazeera to defend the network’s cameraman Mohamed Badr Eddin, detained for more than a month, and their reporter Abdullah al-Shamy who remained in jail for close to a year.

Speaking about the audio recording presented by the prosecution against his clients, Said told EgyptSource, “When the audio track was played in court, I demanded the court refer it to technical inspection and my request was ignored. So when the judge asked my clients if the voices heard in the track were their voices I advised them to deny it, and they did.”

Said never denied the authenticity of the recording, nor was it independently verified.

The lawyer argued the three students should have never been in the Al-Jazeera trial alongside the network’s journalists, and that the legal case against them was extremely weak. He cited their arrest without a warrant, and a complete lack of evidence linking them to the Al-Jazeera English reporters, as his reasons.

“The authorities failed to differentiate between the banned Al-Jazeera Mubashir Misr and the English channel, wrongfully put all the defendants together, and failed to present evidence to back its claims.”

Nonetheless, the three students, accused of providing the three Al-Jazeera journalists with footage, were each sentenced to seven years in prison. The other two students, Ahmed and Anas, were acquitted, and were never linked in the case documents to those sentenced.

Mohamed Fahmy confronted the judge, Nagy Shehata, over the false claims linking him to the students. “You have had our computers, emails and our cell phones for six months, there are no emails or phone numbers linking us to the students standing in the cage, I wish there was anything to defend myself against.”

Al-Jazeera Journalism in a Post-Morsi Egypt

One day after Morsi’s ouster, the offices of Al-Jazeera Mubashir Misr were shut down, along with other Muslim Brotherhood owned or affiliated satellite channels and media offices. According to former Al-Jazeera workers, the channel became actively present at the Raba’a al-Adaweya Media Center—a newsroom set up and operated by Muslim Brotherhood officials inside the mosque and multi-story extension at the heart of the sit in.

“Al-Jazeera Mubashir Misr and Arabic offices were shutdown, and they were facing security intimidation, so they relied heavily on young freelancers in the Raba’a al-Adaweya Media Center. Some of them worked officially with the network and others worked on a freelance basis,” Osama al-Sayad, a former Al-Jazeera freelance producer told EgyptSourcein a Skype interview. He fled Egypt after a security raid on his residence in Cairo’s Hadayek al-Qubba neighborhood.

According to al-Sayad, this is where Alaa Adel’s connection to the students came in to the picture. “Abdelraouf and his colleagues didn’t work directly with Al-Jazeera, but dealt with Alaa Adel,” he explained. “The channel has continued to work with similar policies and tactics but they don’t offer the same quality as before due to the security’s infiltration of the media community, and its pursuing of the channel’s workers,” al-Sayad added. “There are also many people who volunteer to cover protests and other events for the channel without being paid or hired.”

According to Alaa Adel himself, however, he was not the direct conduit to Al-Jazeera. “I am a documentary filmmaker and I met the students who took part in the pro-Morsi protests and were interested in covering such activities,” Adel told EgyptSource. “So I linked them to someone who I believe was among many volunteers who wanted to serve the cause.”Adel never mentioned the name of the ‘volunteer’ he spoke of, saying only, “He is a member of the Muslim Brotherhood’s media committees who had access to many cameras filming in different locations and was supplying Al-Jazeera with the footage.”

“I also introduced them to the owner of the apartment [Ahmed Abdu] who is a friend living outside of Egypt and who agreed to host them temporarily,” he added. According to Adel, that was two weeks before their arrest.

Adel said he had no knowledge of the audio track played by the prosecution, and was confused to know that all three students testified against him, but his name was never listed among the defendants.

“After their arrest, I learned from three people released from custody that the state security officers were asking about me and my whereabouts. Another friend of mine was arrested and testified against me as well, so I decided to leave Egypt and came to Istanbul.”

The Brunt of Al-Jazeera’s Misconduct

Since the establishment of the Qatari network’s Egypt arm, Al-Jazeera Mubashir Misr, in March 2011, the channel has shown a clear bias toward the Muslim Brotherhood organization and its political activities in Egypt. But after Morsi’s ouster and the stifling conditions the channel was facing, it started relying on activists—who are highly sympathetic and ideologically aligned with the brotherhood—more than it did on journalists.

“The Al-Jazeera three had no clue Mubashir Misr and Arabic channels were using footage produced by active members of the Muslim Brotherhood and its Anti-Coup Alliance, the first time they ever met them was in court,” a source with comprehensive knowledge of the case said on condition of anonymity.

“Fahmy, as Cairo bureau chief of Al-Jazeera English, was kept in the dark that the network was paying for content produced by the biggest opposition force in Egypt, the Muslim Brotherhood.”

And while many would consider this citizen journalism, the source insists, “This specific case is different. In a time of warring regimes and a banned channel kept under the microscope, accepting material made by Muslim Brotherhood active youth leaves the channel under scrutiny and liable to prosecution.

“It is like giving a camera to Hezbollah or Hamas to film their frontline. What do you think the footage will portray?” said the source who described the students as “Muslim Brotherhood youth who are entrenched in the organization of protests and sit-ins.”

Many are as equally critical of the Egyptian regime’s role as they are of Al-Jazeera. “I am totally against the imprisonment of any journalist in this case and other cases,” Hisham Kassem, a prominent Egyptian publisher and founder of the country’s leading independent newspaper Al-Masry Al-Youm, told EgyptSource.

“The Egyptian regime has to understand that the media sector is as important as any sector of the economic and political structure of Egypt,” added Kassem. “Such violations inflict harm not only on the country’s image and political stability but also on the overall economy.”

As for Al-Jazeera, Kassem said “I cannot understand how Al-Jazeera destroyed its reputation as the Middle East’s leading media platform to become a servant of Qatar’s foreign policy.”

Hanan Fikry, a board member of the Egyptian Press Syndicate that took part in the defense of Al-Jazeera jailed journalists, says, “Al-Jazeera’s behavior and the way it operates makes it impossible to defend the victims.”

“The Al-Jazeera network, which is fully capable of covering the events fairly and professionally, decided to become a part of the dispute it covers, and sided with the Muslim Brotherhood against the Egyptian regime. What Al-Jazeera is doing simply contradicts media ethics across the world and destroys its own credibility.”

Days earlier, Fahmy described Al-Jazeera’s actions in a letter he sent from his prison to Canadian Journalists for Free Expression, CJFE.”Journalism aside, to opt to abuse your media platform to challenge an already aggravated government only leaves your frontline reporters exposed and as easy prey – a bargaining chip,” said Fahmy.

“I call on CJFE through this rare communiqué to escalate their watchdog approach toward governments and media organizations alike,” said Fahmy’s letter, read on his behalf while he remains behind bars.

Read the Court Documents:

![]() Ministry Of Interior Report: The interior ministry’s criminal evidence department listed Fahmy, Greste, and Mohamed along, with the three students Abdelraouf, Saad, and Abdelhamid in one report. Equipment confiscated from all six defendants were presented together despite being seized in different location on different dates.

Ministry Of Interior Report: The interior ministry’s criminal evidence department listed Fahmy, Greste, and Mohamed along, with the three students Abdelraouf, Saad, and Abdelhamid in one report. Equipment confiscated from all six defendants were presented together despite being seized in different location on different dates.

![]() National Security Report: A report by the National Security officer described Fahmy as “member of the Muslim Brotherhood terrorist organization.” The report accused Fahmy of “holding meetings with members of the terrorist Muslim Brotherhood organization.” Page 2 of the report named all three students as members of the network run by Fahmy, and added that they operated from the Moqattam residence which was rented by Ahmed Abdu’s Al-Nour Media Production Company. The third page of the National Security report requested an arrest warrant for all three students, which shows that they were unlawfully arrested without a warrant at the Moqattam police checkpoint.

National Security Report: A report by the National Security officer described Fahmy as “member of the Muslim Brotherhood terrorist organization.” The report accused Fahmy of “holding meetings with members of the terrorist Muslim Brotherhood organization.” Page 2 of the report named all three students as members of the network run by Fahmy, and added that they operated from the Moqattam residence which was rented by Ahmed Abdu’s Al-Nour Media Production Company. The third page of the National Security report requested an arrest warrant for all three students, which shows that they were unlawfully arrested without a warrant at the Moqattam police checkpoint.

![]() Testimony by Khaled Abdelraouf: Page 6 of his testimony reads: “I independently filmed protests since the revolution, then I joined the Freedom and Justice Party’s media office but I didn’t like the way they operated.” Page 8 of testimony reads: “I met Alaa Adel during the sit in and I believe he is a member of the Muslim Brotherhood…. Alaa offered me to work with him and told me that he will establish a documentary film production company.”

Testimony by Khaled Abdelraouf: Page 6 of his testimony reads: “I independently filmed protests since the revolution, then I joined the Freedom and Justice Party’s media office but I didn’t like the way they operated.” Page 8 of testimony reads: “I met Alaa Adel during the sit in and I believe he is a member of the Muslim Brotherhood…. Alaa offered me to work with him and told me that he will establish a documentary film production company.”

![]() Testimony by Suhaib Saad : Saad testified: “Alaa Adel offered me to film protests in return for 1,000 pounds per month.” Saad added that Adel gave him a Canon D600 professional camera.” He added that he didn’t know which channels Adel dealt with but know of “one interview with the mother of a martyr was aired on Al-Jazeera’s Arabic channel.”

Testimony by Suhaib Saad : Saad testified: “Alaa Adel offered me to film protests in return for 1,000 pounds per month.” Saad added that Adel gave him a Canon D600 professional camera.” He added that he didn’t know which channels Adel dealt with but know of “one interview with the mother of a martyr was aired on Al-Jazeera’s Arabic channel.”

![]() Testimony by Shadi Abdelhamid: Abdelhamid testified that he was detained in the Moqattam police checkpoint along with Abdelraouf and Saad, a testimony confirmed by the two. The three testimonies show they were unlawfully detained without a warrant and that the police department sought the warrant after the arrest.

Testimony by Shadi Abdelhamid: Abdelhamid testified that he was detained in the Moqattam police checkpoint along with Abdelraouf and Saad, a testimony confirmed by the two. The three testimonies show they were unlawfully detained without a warrant and that the police department sought the warrant after the arrest.

![]() Verdict Report: Includes details of the audio recording that was used to incriminate the three students.

Verdict Report: Includes details of the audio recording that was used to incriminate the three students.

Mohannad Sabry is an Egyptian journalist based in Cairo. He was a finalist for the 2011 Livingston Award, and his articles have been published by The Miami Herald, among several McClatchy newspapers, The Philadelphia Inquirer, The Washington Times, GlobalPost and others. Sabry is currently writing a book on the security and political situation in the Sinai Peninsula.

Image: Photo: Ahram