Still, Ukrainians Wait to See Concrete Steps to End a System of Graft

Ukraine’s new government is on track to pass a painfully austere budget by the end of the year, according to the Atlantic Council’s Kyiv-based senior fellow, Brian Mefford. The other center of attention is the government’s establishment of a National Anti-Corruption Bureau, Mefford writes in his blog this week.

Whatever the balance in the government’s motivations–the IMF’s demands for reforms or a sincere desire to fight corruption—it has officially created its promised National Anti-Corruption Bureau, which some have dubbed “Ukraine’s FBI.”

As the new Cabinet of Ministers itself did this month, the bureau starts its life with a roster of prominent leaders who have shown energy and skill in pushing reforms. Still, it will have to show concrete steps to reduce corruption and overcome the legacy of past reform efforts that failed.

As Mefford notes, the bureau’s nine members are appointed, three each, by the parliament, the president and the Cabinet:

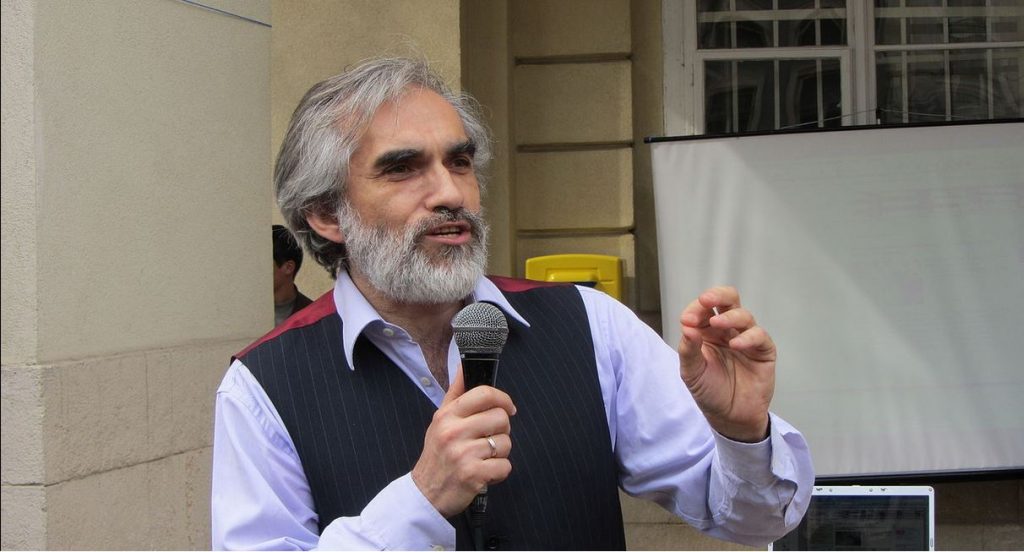

President Poroshenko’s appointees are the prominent historian Yaroslav Hrytsak; the director of the Kharkiv Human Rights Protection Group, Yevhen Zakharov; and Refat Chubarov, the chairman of the Mejlis, the broad umbrella group representing Crimean Tatars. With Chubarov’s appointment, and the prominent role given to Tatar icon Mustafa Dzhemilev as an MP and a member of the Petro Poroshenko Bloc, the president continues to highlight the plight of the Crimean Tatars.

The Cabinet of Ministers selected Yosef Zisels, the highly regarded chairman of the Association of Jewish Organizations and longtime Helsinki Group member; Oleksandra Yankovska, an ad hoc judge for the European Court of Human Rights; and Yuri Butusov, the journalist and chief editor of the news website Censor.net.

The Verkhovna Rada named Yevhen Nishchuk, the EuroMaidan activist who served this year as interim culture minister; constitutional lawyer and former MP Viktor Musiyaka; and Italian prosecutor and director-general of the European Commission’s Anti-Fraud Office, Giovanni Kessler.

Kessler’s appointment extends the new government’s practice of including non-Ukrainian technocrats in politically sensitive roles. (The most prominent instance has been the appointment of three foreigners as ministers—of finance, economy and health.) And Poroshenko proposes to extend it further, having called consistently for a foreigner to direct the National Anti-Corruption Bureau.

According to inside sources, one leading candidate for the director’s post is a Ukrainian-American former assistant US attorney, Bohdan Vitvitsky. (Vivitsky, a Democrat from New Jersey, has written on corruption issues in Ukraine.) Former Georgian President Mikhail Saakashvili also has been mentioned. And a hostile reaction by Saakashvili’s rival, Georgian Prime Minister Irakli Garibashvili, tends to confirm that the idea is under serious consideration by Poroshenko. Former Georgian Deputy Chief Prosecutor David Sakvarelidze also is under consideration.

The key question for Ukrainians and the international community is whether the National Anti-Corruption Bureau will be merely a cosmetic adornment to the longstanding modus operandi—or will be more like the Federal Bureau of Investigation under J. Edgar Hoover. “Given Hoover’s successes in fighting the mafia and Communists, a replication of Hoover’s FBI in Ukraine would be exactly what the doctor ordered,” Mefford concludes.

When do the ‘Bandits’ go to Prison?

With the average Ukrainian increasingly feeling the effect of the economic downturn (due to the war in Donbas and the looting of the state institutions under former President Viktor Yanukovych), there is a growing public sense that “little has changed” with the new government. Prosecutions of Yanukovych-era officials have gone almost nowhere and the Europeans may soon have to lift their sanctions against those individuals. Ukraine’s prosecutor general, Vitaliy Yarema, is receiving increasing criticism for his failure to get a major conviction. Privately, he complains that Poroshenko is holding him back. In wartime, priorities change and Poroshenko must unify the nation rather than divide it.

Nonetheless, the public appetite for the corrupt “bandits” of the former government to go to prison has not abated, and the growing popular frustration is starting to resemble that of about 2006, in the period that followed the pro-democracy Orange Revolution. Failure to put a Yanukovych cabinet-level official and/or oligarch in prison by next spring will lead to major disenchantment with the current government. For Ukrainians, if no officials are sent to prison, then that will de facto mean that the result of last winter’s Euromaidan uprising was not justice, but only a transfer of power from one portion of the elite to another.

Also: Poroshenko Boosts Role in Cabinet with New Appointment

President Poroshenko appointed Vitaliy Kovalchuk as first deputy prime minister on December 26. Kovalchuk is the political right hand of Poroshenko’s electoral ally from last May, former boxing champion Vitaliy Klitschko. (Klitschko was elected mayor of Kyiv as Poroshenko won the presidency.) Kovalchuk’s appointment gives Poroshenko more influence within the Cabinet of Ministers as well as a potential check on his part-ally, part-rival, Prime Minister Arseniy Yatsenyuk. Although Kovalchuk is generally not well liked due to a public perception that he is arrogant, almost everyone agrees that he is effective.

Kovalchuk’s appointment will further erode the machinery of Klitschko’s political party, UDAR, as he is only the latest of many current or former UDAR personnel who are now occupied with government positions and thus have no time for party building. Another UDAR member, Rostaslav Pavlenko, was named Poroshenko’s deputy chief of staff with a domestic policy portfolio. Pavlenko is highly knowledgeable on policy issues and brings smart political instincts to the table. Pavlenko previously served in the secretariat of former President Viktor Yushchenko, and was regarded as one someone who “could get things done.” UDAR’s Vitaliy Chuhunnikov was appointed governor of Rivne. These and other recent appointments have had the effect of strengthening President Poroshenko and his party, perhaps at the expense of UDAR and other parties.

Image: Historian Yaroslav Hrytsak, named to Ukraine’s National Anti-Corruption Bureau, delivers a lecture at the University of Lviv in 2012. Hrytsak also is an award-winning author and a visiting professor at Central European University in Budapest. (Wikipedia/CC License)