The Kremlin’s Trojan Horses

“Since Putin’s return to power in 2012, the Kremlin has accelerated its efforts to resurrect the arsenal of ‘active measures’…” writes Dr. Alina Polyakova in The Kremlin’s Trojan Horses: Russian Influence in France, Germany, and the United Kingdom, a new report from the Atlantic Council’s Dinu Patriciu’s Eurasia Center. Western European democracies are not immune to the Kremlin’s tactics of influence, which seeks to turn Western liberal virtues–free media, plurality of opinion, and openness–into vulnerabilities to be exploited.

Russia’s meddling in other counties’ politics, while shocking to some, is part and parcel of the Kremlin’s toolkit of influence. This report documents how the Russian government cultivates relationships with ideologically friendly political parties, individuals, and civic groups to build an army of Trojan Horses across European polities. This network of political allies, named in the report, serves the Kremlin’s foreign policy agenda that seeks to infiltrate politics, influence policy, and inculcate an alternative, pro-Russian view of the international order.

“Western governments should encourage and fund investigative civil society groups and media that will work to shed light on the Kremlin’s dark networks,” writes the former Foreign Minister of Poland, Radosław Sikorski, in the report’s foreword. The report presents three cases, France, Germany, and the United Kingdom, each written by a leading expert: Dr. Marlene Laruelle, director of the Central Asia Program and associate director of the Institute for European, Russian, and Eurasian Studies at the Elliott School of International Affairs at The George Washington University; Mr. Neil Barnett, chief executive officer of Istok Associates; Dr. Stefan Meister, director, Eastern Europe, Russia, and Central Asia, Robert Bosch Center, German Council on Foreign Relations; and Dr. Alina Polyakova, deputy director of the Dinu Patriciu Eurasia Center and senior fellow with the Future Europe Initiative at the Atlantic Council.

Table of contents

Introduction: The Kremlin’s toolkit of influence in Europe

France: Mainstreaming Russian influence

Germany: Interdependence as vulnerability

United Kingdom: Vulnerable but resistant

Policy recommendations: Resisting Russia’s efforts to influence, infiltrated and inculcate

Foreword

In 2014, Russia seized Crimea through military force. With this act, the Kremlin redrew the political map of Europe and upended the rules of the acknowledged international order. Despite the threat Russia’s revanchist policies pose to European stability and established international law, some European politicians, experts, and civic groups have expressed support for—or sympathy with—the Kremlin’s actions. These allies represent a diverse network of political influence reaching deep into Europe’s core.

The Kremlin uses these Trojan horses to destabilize European politics so efficiently, that even Russia’s limited might could become a decisive factor in matters of European and international security. President Putin increasingly sees that which the West seeks—Europe whole, free, and at peace—not as an opportunity for prosperous coexistence but as a threat to his geopolitical agenda and regime survival.

Moscow views the West’s virtues—pluralism and openness—as vulnerabilities to be exploited. Its tactics are asymmetrical, subversive, and not easily confronted. Western governments have ignored the threat from Putin’s covert allies for too long, but finally, awareness is growing that the transatlantic community must do more to defend its values and institutions.

To that end, Western governments should encourage and fund investigative civil society groups and media that will work to shed light on the Kremlin’s dark networks. European Union member states should consider establishing counter-influence task forces, whose function would be to examine financial and political links between the Kremlin and domestic business and political groups. American and European intelligence agencies should coordinate their investigative efforts through better intelligence sharing. Financial regulators should be empowered to investigate the financial networks that allow authoritarian regimes to export corruption to the West. Electoral rules should be amended, so that publically funded political groups, primarily political parties, should at the very least be required to report their sources of funding.

The Kremlin’s blatant attempts to influence and disrupt the US presidential election should serve as an inspiration for a democratic push back.

The Hon. Radosław Sikorski

Distinguished Statesman, Center for Strategic and International Studies Former Foreign Minister of Poland

Introduction: The Kremlin’s Toolkit of Influence in Europe

Alina Polyakova

Under President Vladimir Putin, the Russian government has reinvigorated its efforts to influence European politics and policy.1Throughout this paper, the terms Russia, Kremlin, and Moscow are used interchangeably to refer to the Russian government under President Vladimir Putin rather than to the people of Russia. The Kremlin’s strategy of influence includes a broad array of tools: disinformation campaigns, the export of corruption and kleptocratic networks, economic pressures in the energy sector, and the cultivation of a network of political allies in European democracies. The ultimate aim of this strategy is to sow discord among European Union (EU) member states, destabilize European polities, and undermine Western liberal values—democracy, freedom of expression, and transparency—which the regime interprets as a threat to its own grasp on power.2Marine Laruelle, Lóránt Gyori, Péter Krekó, Dóra Haller, and Rudy Reichstadt, “From Paris to Vladivostok: The Kremlin Connections of the French Far-Right,” Political Capital, December 2015, http://www.politicalcapital.hu/wp-content/uploads/PC_Study_Russian_Influence_France_ENG.pdf.

Since Putin’s return to power in 2012, the Kremlin has accelerated its efforts to resurrect the arsenal of “active measures”—tools of political warfare once used by the Soviet Union that aimed to influence world events through the manipulation of media, society, and politics.3Vaili Mitrokhin and Christopher Andrew, The Mitrokhin Archive: The KGB and Europe and the West (London: Gardners Books, 2000). Indeed, influence operations are a core part of Russia’s military doctrine. In 2013, Chief of the Russian General Staff General Valery Gerasimov described a new approach for achieving political and military goals through “indirect and asymmetric methods” outside of conventional military intervention.4Charles K. Bartles, “Getting Gerasimov Right,” Military Review, January/February 2016, pp. 30-38, http://fmso.leavenworth.army.mil/documents/Regional%20security%20europe/MilitaryReview_20160228_art009.pdf These “non-linear” methods, as Gerasimov also called them, include manipulation of the information space and political systems.

Since Putin’s return to power in 2012, the Kremlin has accelerated its efforts to resurrect the arsenal of “active measures”. . .

Russia under Putin has deployed such measures with increasing sophistication in its immediate neighborhood.5Orysia Lutsevych, “Agents of the Russian World: Proxy Groups in the Contested Neighborhood,” Chatham House, April 2016. Ukraine, Georgia, Moldova, and the Central Asian countries have long been exposed to the Kremlin’s attempts to meddle in elections, prop up pro-Russian governments, support anti-Western political parties and movements, threaten energy security with “gas wars,” spread lies through its well-funded media machine, and, when all else fails, intervene militarily to maintain control over its neighbors.

The full range of the Kremlin’s active measures capabilities was on display during the early stages of Russia’s intervention in Ukraine following the 2013 Maidan revolution that toppled Putin’s close ally, Ukraine’s former president, Viktor Yanukovych. In Ukraine, Russia’s state-sponsored propaganda quickly moved to brand the peaceful demonstrations in Kyiv as a fascist coup intent on repressing Russian speakers in Ukraine. Its agents of influence in civil society attempted to incite separatist rebellions in Russian-speaking regions, which ultimately failed. And Russia’s infiltration of Ukraine’s security services weakened the new government’s ability to respond, as Russia took over Crimea and sent troops and weapons into eastern Ukraine in the spring of 2014.

The strategy is not limited to what Russia considers its “near abroad” in the post-Soviet space. Through its state-sponsored global media network, which broadcasts in Russian and a growing number of European languages, the Kremlin has sought to spread disinformation by conflating fact and fiction, presenting lies as facts, and exploiting Western journalistic values of presenting a plurality of views.6Peter Pomerantsev and Michael Weiss, “The Menace of Unreality: How the Kremlin Weaponizes Information, Culture, and Money,” Institute of Modern Russia and the Interpreter, November 2014. Through its network of political alliances across the post-Soviet space, Russia seeks to infiltrate politics, influence policy, and inculcate an alternative, pro-Russian view of the international order. Whereas the ultimate goal in the near abroad is to control the government or ensure the failure of a pro-Western leadership, in Europe, the goal is to weaken NATO and the EU.

In Central and Eastern Europe, the Kremlin’s opaque connections with business leaders, politicians, and political parties facilitate corruption and quid pro quo relationships. The aim here, as elsewhere, is to sway, through coercion and corruption, the region’s policies away from European integration and toward Russia. The Kremlin does so by strategically exploiting vulnerabilities in Central and Eastern Europe’s democracies, such as weak governance, underdeveloped civil society space, and underfunded independent media, while cultivating relationships with rising autocratic leaders and nationalist populist parties; a web of influence that one report describes as an “unvirtuous cycle” that “can either begin with Russian political or economic penetration and from there expand and evolve, in some instances leading to ‘state capture’.”7Heather A. Conley, James Mina, Ruslan Stefanov, and Martin Vladimirov, “The Kremlin Playbook: Understanding Russian Influence in Central and Eastern Europe,” Center for Strategic and International Studies, October 2016, https://csis-prod.s3.amazonaws.com/s3fs-public/publication/160928_Conley_ KremlinPlaybook_Web.pdf.

Western Europe is not exempt from Russia’s manipulations. In Western countries, the Russian government cannot rely on a large and highly concentrated Russian-speaking minority as its target of influence and lacks the same historical or cultural links. In this context, the Kremlin’s destabilization tactics have been more subtle and focused on: (1) building political alliances with ideologically friendly political group and individuals, and (2) establishing pro-Russian organizations in civil society, which help to legitimate and diffuse the regime’s point of view.

The web of political networks is hidden and non-transparent by design, making it purposely difficult to expose. Traceable financial links would inevitably make Moscow’s enterprise less effective: when ostensibly independent political figures call for closer relations with Russia, the removal of sanctions, or criticize the EU and NATO, it legitimizes the Kremlin’s worldview. It is far less effective, from the Kremlin’s point of view, to have such statements come from individuals or organizations known to be on the Kremlin’s payroll.8Alina Polyakova, “Why Europe Is Right to Fear Putin’s Useful Idiots,” Foreign Policy, February 23, 2016, http://foreignpolicy.com/2016/02/23/why-europe-is-right-to-fear-putins-useful-idiots/.

Since the 2008 economic crisis, which provoked mistrust in the Western economic model, the Kremlin saw an opportunity to step up its influence operations in Europe’s three great powers—France, Germany, and the United Kingdom (UK). Russia has developed well-documented relationships with anti-EU, far-right political parties and leaders.9Alina Polyakova, “Putinism and the European Far Right,” Institute of Modern Russia, January 19, 2016, http://imrussia.org/en/analysis/world/2500-putinism-and-the-european-far-right. The influence strategy is tailored to each country’s cultural and historical context. In some cases, such as the National Front in France, the Kremlin’s financial support for such parties is explicit (see Laruelle, chapter 1). In the UK, it is more opaque as the UK remains more resistant to the Kremlin’s efforts. While the on-and-off leader of the UK Independence Party, Nigel Farage, is unabashedly pro-Russian, other links occur through multiple degrees of separation and chains of operators across sectors (see Barnett, chapter 3). And in Germany, network building occurs through organizational cooperation and cultivation of long-term economic links, which open German domestic politics to Russian penetration (see Meister, chapter 2).

Thus, the Kremlin’s concerted effort to establish networks of political influence has reached into Europe’s core. Be they Putinverstehern, useful idiots, agents of influence, or Trojan Horses, the aim is the same: to cultivate a network of organizations and individuals that support Russian economic and geopolitical interests, denounce the EU and European integration, propagate a narrative of Western decline, and vote against EU policies on Russia (most notably sanctions)—thus legitimating the Kremlin’s military interventionism in Ukraine and Syria, weakening transatlantic institutions, and undermining liberal democratic values.10Mitchell Orenstein and R. Daniel Keleman, “Trojan Horses in EU Foreign Policy,” Journal of Common Market Studies, 2016, doi: 10.1111/jcms.12441.

The Kremlin’s influence operations are not just tactical opportunism, though they certainly are that as well. Behind the network webs, the long-term goal is to upend the Western liberal order by turning Western virtues of openness and plurality into vulnerabilities to be exploited.11Alina Polyakova, “Strange Bedfellows: Putin and Europe’s Far Right,” World Affairs Journal, September/October 2014, http://www.worldaffairsjournal.org/article/strange-bedfellows-putin-and-europe%E2%80%99s-far-right. These efforts were long ignored, overlooked, or denied by Western European countries. But they are now bearing fruit for the Kremlin. Anti-EU, pro-Russian parties, driven by domestic discontent but fanned by Russian support, are gaining at the polls; the UK has voted to leave the EU, undermining the vision of the European project of an ever closer Union; the refugee crisis, partially facilitated by Russia’s military intervention in Syria, is driving a wedge between European nation-states; trust in establishment parties and media is on the decline; and self-proclaimed illiberal leaders in Poland and Hungary are forging an anti-democratic path that looks East rather than West.

Western democracies have not yet come to terms with Russia’s increasing influence in their politics and societies. This lag in response to the slowly metastasizing threat is likely due to Western European leaders’ attention being focused elsewhere: Europe has been muddling through its many crises for the last decade, and the need to solve Europe’s immediate problems, including economic stagnation, refugee inflows, and the threat of terrorism, takes primacy over incrementally brewing influence efforts by a foreign power. However, Western hubris also has a role to play: European leaders have been reluctant to admit that the world’s oldest democracies can fall prey to foreign influence. Open and transparent liberal democratic institutions are, after all, supposed to be a bulwark against opaque networks of influence. Yet, they are not. German, French, and British leaders must come to terms with their countries’ vulnerabilities to Russian tactics of influence or risk undermining the decades of progress the EU has made in ushering in an era of unprecedented value-based cooperation.

France: Mainstreaming Russian influence

Marlene Laruelle

Political landscape

France is currently being shaken by a dneep political crisis, which seems to have its origins in France’s slow recovery after the economic crisis and is characterized by low voter turnout in elections, rising public distrust toward institutions and politicians, emergence of anti-establishment parties, and tensions around issues of national identity and terrorism. In this context, the rise of the far-right populist Front National (National Front, FN) is transforming France’s political landscape. The party’s leader and daughter of its founder, Marine Le Pen, has modernized the FN’s nationalist narrative and broadened the party’s appeal by whitewashing its public image of extremist elements, such as open anti-Semitism, racism, Holocaust denial, radical Catholicism, and support for French Algeria. In their place, Le Pen brought in more modern and consensual aspects, such as defense of French laïcité (secularism) against Islam, conflation of migrants with Islamism and terrorism, denunciation of the European Union (EU) and its purported dismantlement of the nation-state, and a protectionist economic agenda.

After Germany and the United Kingdom, France is the top economic and military power in Europe. Yet, of those three states, France alone has a major far-right, Eurosceptic, and openly pro-Russian party. In the spring of 2017, the country will hold presidential elections, and Marine Le Pen is likely to receive enough support in the first round (25-30 percent) to qualify for the second round. While she is unlikely to win the presidency, her participation as a potential presidential candidate will be a victory for her party and its goal to shift the political landscape to the right. Already, many important figures in the center-right party, Les Républicains (Republicans), are pushing for a more rightist agenda, focused on identity issues and security, in order to “poach” the FN electorate. Both the FN and part of the Republicans around Nicolas Sarkozy share something else: they are supporters of warmer relations with Russia. While the FN is openly pro-Putin, the Republicans are more nuanced, but several of the center-right parties’ main figures have close ties with Moscow and hope for better relations. The 2017 elections will not only decide the future of France for the next five to ten years, but they could also change Paris’s relationship with Russia.

Key pro-Russian actors in France

There are three pro-Russian camps in France’s political landscape: the far right, the far left, and the Republicans.

On the far right, the FN is Moscow’s most vocal supporter, where almost no dissenting anti-Russian voices are heard. The FN is also the only major far-right party to openly accept financial support from Russia. In 2014, it received a nine million Euros loan from the Moscow-based First Czech Russian Bank.12Ivo Oliveira, “National Front Seeks Russian Cash for Election Fight,” Politico, February 19, 2016, http://www.politico.eu/article/le-pen-russia-crimea-putin-money-bank-national-front-seeks-russian-cash-for-election-fight/. In the spring of 2016, Le Pen asked Russia for an additional twenty-seven million Euros loan to help prepare for the 2017 presidential and parliamentary campaigns, after having been refused a loan by French banks. Some analysts13David Chazan, “Russia ‘Bought’ Marine Le Pen’s Support Over Crimea,” Telegraph, April 4, 2015, http://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/worldnews/europe/france/11515835/Russia-bought-Marine-Le-Pens-support-over-Crimea.html. interpret this financial support as representing a quid pro quo, in which the FN is rewarded for the backing of Russia’s position on Crimea. However, as discussed in the following sections, the links between the FN and Putin’s regime are much deeper than purely financial and circumstantial.

The far left (the Communist party and the Left Party), while generally pro-Russian, is more nuanced in its views. Russia is highly valued and supported by those with a souverainist stance (i.e., those skeptical toward the European project and advancing a more traditional statist, and Jacobin, point of view). Among the most notable members of this group is the vocal politician Jean-Luc Mélenchon, a former Socialist Party member who now advocates for a more radical leftist position, favoring a close relationship with Russia. The very weak (currently representing approximately 3 percent of the electorate) Communist Party, too, by tradition, takes a Russophile position.

The center-right Republicans are more divided on their relationship to Russia. However, there is a distinct pro-Russian group around the former Prime Minister Francois Fillon, including the former State Secretary Jean de Boishue, Fillon’s adviser and a specialist on Russia, and Igor Mitrofanoff. Similarly, many people around Nicolas Sarkozy such as Thierry Mariani, member of the National Assembly and vice-president of the French-Russian Parliamentary Friendship Association, have been publically supportive of the Russian position on the Ukrainian crisis. Former Prime Minister Dominique de Villepin embodies another trend of the Republicans: favorable to Russia in the De Gaulle tradition of balancing between the United States and Russia/the Soviet Union, without openly supporting Putin’s position.

On the far right, the FN is Moscow’s most vocal supporter, where almost no dissenting anti-Russian voices are heard.”

The Republicans’ pro-Russian stance is partly based on the party’s deep connections with elements of French big business, which have operations in Russia, mostly in the defense industry (Thales, Dassault, Alstom), the energy sector (Total, Areva, Gaz de France), the food and luxury industry (Danone, Leroy-Merlin, Auchan, Yves Rocher, Bonduelle), the transport industry (Vinci, Renault), and the banking system (Société Générale). Many chief executive officers (CEOs) of these big industrial groups have close connections to the Kremlin’s inner circle and have been acting as intermediaries of Russian interests and worldviews for the Republicans. This was the case with Christophe de Margerie, Chief Executive of the French oil corporation, Total SA, who had a close relationship with Putin. De Margerie died in a plane crash in Moscow in 2014 after returning from a business meeting with Prime Minister Dmitri Medvedev. In his condolences to the French President Francois Hollande, Putin called de Margerie a “true friend of our country,” who had “pioneered many of the major joint projects and laid the foundation for many years of fruitful co-operation between France and Russia in the energy sector.”14“‘Shock & Sadness’: Total CEO Dies in Moscow Plane Crash,” RT, October 21, 2014, https://www.rt.com/business/197724-christophe-de-margerie-moscow-crash/.

France has been leading in terms of cooperation with Russia in the space sector (the Russian missile Soyuz launched from the spaceport Kourou in French Guiana) and in the military-industrial complex (for instance, the joint venture between Sagem and Rostekhnologii). In 2010, the signing of a contract for the sale of two Mistral-class amphibious assault ships to Russia—now dead as a collateral victim of the Ukrainian crisis—was one of the first major arms deals between Russia and a NATO country, symbolizing the leading role of France and the French military sector in building bridges with Russia.

Among the center left, fewer figures emerge as pro-Russian. In the Socialist Party, one can mention Jean-Pierre Chevènement, special representative for relations with Russia at the French Ministry of Foreign Affairs, and Pascal Terrasse, general secretary of the Parliamentary Assembly of Francophony, as well as member of the National Assembly Jérôme Lambert.15More details in Nicolas Hénin, “La France russe. Enquête sur les réseaux Poutine,” Fayard, May 25, 2016, http://www.fayard.fr/la-france-russe-9782213701134.

In addition to the political networks, there is a powerful and well-structured net of “civil society” organizations and think tanks that promote Russian interests. The most well-known among them is the Institute for Democracy and Cooperation (IDC), led by Natalia Narochnitskaya, a high priestess of political Orthodoxy since the 1990s and former member of parliament (MP) in the Russian Duma. John Laughland, the Eurosceptic British historian and frequent commentator on the Russian-funded television network RT, is director of studies at the IDC, which is funded by Russian “charitable NGOs” (non-governmental organizations). The Russian government makes use of the long-established cultural institutions associated with the presence of an important Russian diaspora in France that dates back to the 1920s and the Soviet period. It contributes to a myriad of Russian associations such as the Dialogue Franco-Russe, headed by Vladimir Yakunin, who was head of Russian Railways and a close Putin adviser until August 2015, and Prince Alexandre Troubetzkoy, representative of Russian emigration. Paris is also home to the largest Russian Orthodox Church in Europe, which opened in fall 2016 in the center of Paris. The Moscow Patriarchate’s close relationship with the Kremlin helps project Russia’s “soft” power in Europe.16Andrew Higgins, “In Expanding Russian Influence, Faith Combines with Firepower,” New York Times, September 13, 2016, http://www.nytimes.com/2016/09/14/world/europe/russia-orthodox-church.html?_r=0.

Building networks of influence

Since Putin took office in 2012 for his third term as Russia’s president, the Russian government has ramped up its efforts to build networks of relationships with like-minded political organizations and individuals in France. Putin has publically supported Marine Le Pen since she became FN president in 2011. The FN finds common ground with several ideological components of Putin’s regime: authoritarianism (the cult of the strong man), anti-American jockeying (the fight against US unipolarity and NATO domination), defense of Christian values, rejection of gay marriage, criticism of the European Union, and support for a “Europe of Nations.” Following the 2014 Ukraine crisis and Russia’s subsequent international condemnation, Marine Le Pen has emerged with even greater praise for the Russian leader. In February 2014, as Russia was in the process of its military takeover of Crimea, she said: “Mr. Putin is a patriot. He is attached to the sovereignty of his people. He is aware that we defend common values. These are the values of European civilization.”17“Marine Le Pen fait l’éloge de Vladimir Poutine ‘le patriote’,” Le Figaro, May 18, 2014, http://www.lefigaro.fr/politique/le-scan/citations/2014/05/18/25002-20140518ARTFIG00118-marine-le-pen-fait-l-eloge-de-vladimir-poutine-le-patriote.php. She then called for an “advanced strategic alliance” with Russia,18Marine Turchi, “Les réseaux russes de Marine Le Pen,” Mediapart, February 19, 2014, http://www.mediapart.fr/journal/france/190214/les-reseaux-russes-de-marine-le-pen. which should be embodied in a continental European axis running from Paris to Berlin to Moscow. Regarding the Ukrainian crisis, the FN completely subscribes to the Russian interpretation of events and has given very vocal support to Moscow’s position.19“Le Pen soutient la Russie sur l’Ukraine,” Le Figaro, April 12, 2014, http://www.lefigaro.fr/flash-actu/2014/04/12/97001-20140412FILWWW00097-le-pen-soutient-la-russie-sur-l-ukraine.php. The party criticized the Maidan revolution, blaming the EU for “[throwing] oil on the fire.”20“L’Europe responsable de la crise en Ukraine (Marine Le Pen),” Sputnik, June 1, 2014, http://french.ruvr.ru/news/2014_06_01/LEurope-est-responsable-de-la-crise-en-Ukraine-Marine-Le-Pen-4473/.

The party also supports the Kremlin’s vision for a federalized Ukraine that would give broad autonomy to Russian-speaking regions and the occupied territories of the so-called Donetsk and Luhansk People’s Republics.

Russia’s financial support for the FN’s campaign activities are further evidence of the Kremlin’s investment in the party’s political future, but it is not the full picture. Since 2012, the FN has become increasingly active in building its relations with the Russian government, including several trips by high-ranking leaders: Marion Maréchal-Le Pen, Marine’s niece and France’s youngest MP, travelled to Moscow in December 2012. Bruno Gollnisch, executive vice president of the FN and president of the European Alliance of National Movements (AEMN) went in May 2013, and Marine Le Pen and FN vice president Louis Aliot both went to Russia in June 2013. During a second trip in April 2014, Marine Le Pen was accorded high political honors as she was received by President of the Duma Sergei Naryshkin, Head of the Duma’s Committee on Foreign Affairs Aleksei Pushkov, and Deputy Prime Minister Dmitri Rogozin.21Natalia Kanevskaya, “How the Kremlin Wields Its Soft Power in France,” Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty, June 24, 2014, http://www.rferl.org/content/russia-soft-power-france/25433946.html

Russia’s financial support for the FN’s campaign activities are further evidence of the Kremlin’s investment in the party’s political future. . .

Several Russophile figures surround the president of the FN and have enhanced the party’s orientation toward Russia. The most well-known in this circle is Aymeric Chauprade, an FN international advisor and European deputy who is close to the Orthodox businessman Konstantin Malofeev,22Estelle Gross, “6 Things to Know About the Intriguing Aymeric Chauprade,” L’Obs, October 28, 2015, http://tempsreel.nouvelobs.com/politique/20151028.OBS8489/air-cocaine-6-choses-a-savoir-sur-l-intrigant-aymeric-chauprade.html. one of the supposed funders of the Donbas insurgency. Chauprade was invited to act as an election observer during the March 2014 “referendum” on Crimea’s annexation, for which he gave his approval.23Anton Shekhovtsov, “Pro-Russian Extremists Observe the Illegitimate Crimean ‘Referendum’,” Anton Shekhovtsov’s blog, March 17, 2014, http://anton-shekhovtsov.blogspot.com/2014/03/pro-russian-extremists-observe.html. Xavier Moreau, a former student of Saint-Cyr, France’s foremost military academy, and a former paratrooper who directs a Moscow-based consulting company Sokol, seems to have played a central role in forming contacts between FN-friendly business circles and their Russian counterparts. Fabrice Sorlin, head of Dies Irae, a fundamentalist Catholic movement, leads the France-Europe-Russia Alliance (AAFER). The FN also cultivates relations with Russian émigré circles and institutions representing Russia in France. The FN’s two MPs, Marion Maréchal-Le Pen and Gilbert Collard, are both members of a French-Russian friendship group. Marine Le Pen seems to have frequently met in private with the Russian ambassador to France, Alexander Orlov. Moreover, several FN officials have attended debates organized by Natalia Narochnitskaya, the president of the Paris-based Institute for Democracy and Cooperation.24All these elements have been investigated by Mediapart’s journalist Marine Turchi, who specializes in following the Front National. See her tweets at https://twitter.com/marineturchi.

Among the Republicans, pro-Russian positions emerged particularly vividly during the Ukrainian crisis. The first delegation to visit Crimea in the summer of 2015, against the position of the French Ministry of Foreign Affairs, consisted mainly of Republican MPs, but also included a few Socialist party MPs. Some in the group supported Crimea’s annexation, such as MP Nicolas Dhuicq, close to former Prime Minister Fillon, who stated “We think that the Russian president did what he had to do – protect the people from civil war. If Crimea was not back to Russia, there would be a civil war here with the extremists of the Ukrainian government.”25“Les deputes francais en visite en Russie denoncent la ‘stupidite de la politique des sanctions’,” RT, July 23, 2015, https://francais.rt.com/international/4726-deputes-francais-denoncent-sanctions. Leading the delegation, Thierry Mariani had already stated on his Twitter account on March 1, 2014: “How can one be for self-determination when it comes to Kosovo and against when it comes to the Crimea?” European Parliament Deputy Nadine Morano was more moderate and only insisted on the need for a renewed dialogue with Russia, either in the name of diplomatic cooperation over the Middle East, or on behalf of the French peasants who were hurt by Russia’s countersanctions on European agricultural products. The trip to Crimea was repeated in the summer of 2016 by another delegation—out of the eleven participants, ten were Republican party members and one was a former member of the Socialist party.26Benedict Vitkine, “Des parlementaires francais se rendent de nouveau en Crimee,” Le Monde, July 29, 2016, http://www.lemonde.fr/europe/article/2016/07/29/pour-la-deuxieme-annee-consecutive-un-groupe-de-parlementaires-francais-se-rend-en-crimee_4976310_3214.html. Many of these deputies, from both the National Assembly and the Senate, were also present at the June 2016 parliamentary initiative that called for discontinuing European sanctions against Russia.

However, voting patterns among the French electorate do not translate into anything related to Russia. As in any other country, the electorate is mostly shaped by domestic issues and socioeconomic perceptions. Foreign policy themes that may influence patterns of voting would be only related to the future of the European Union and to the Middle East, and even then closely connected to domestic interests—France’s status in Europe and antiterrorism strategy. Positioning toward Russia, while discussed among the political class, does not determine voting patterns.

Understanding the French-Russian Connection

France is firmly rooted in the Euro-Atlantic community and follows the general European consensus on the Ukrainian crisis, the annexation of Crimea, and the sanctions on Russia. However, bilateral relations are still determined by the legacy of De Gaulle, whose diplomacy from 1944 onward sought to approach Soviet Russia as a counterbalance to the power of the United States. Parts of the French political elite and military establishment, therefore, share a positive view of Russia in the name of a continental European identity that looks cautiously toward the United States and the transatlantic commitment.

Several other elements shape France’s relatively positive view of Russia. France hosts an important Russian diaspora, historically rooted, and has no specific links with Ukraine. Russia does not present a direct security or energy threat to France, which has no pipelines over which conflicts might occur. Paris usually delegates to Germany the leading role when dealing with issues related to the Eastern Partnership, as it prefers to be recognized as having a key role in dealing with Mediterranean issues and the Muslim world more generally. Seen from Moscow, France is appreciated for its intermediate position. President Sarkozy’s ability to secure agreements between Moscow and Tbilisi during the Russian-Georgian crisis of August 2008 was positively received by the Russian elite.

The French position toward Russia should also be understood in the current context of high uncertainties about the future of the Middle East—mainly the Syrian war, but also in the context of Libya, the growing threat closer to France. Repeated terrorist actions, a significant number of young people leaving to Syria, and the refugee crisis push French foreign policy to welcome Russia’s involvement in the Middle East and to see Russia more as an ally than an enemy. This was plainly stated by President Francois Hollande at the July 2016 Warsaw NATO summit: “NATO has no role at all to be saying what Europe’s relations with Russia should be. For France, Russia is not an adversary, not a threat. Russia is a partner, which, it is true, may sometimes, and we have seen that in Ukraine, use force which we have condemned when it annexed Crimea.”27“Hollande: Russia Is a Partner, Not a Threat,” Radio Free Europe/Radio Liberty, July 8, 2016, http://www.rferl.org/content/hollande-russia-is-a-partner-not-a-threat/27847690.html. The October 2016 diplomatic crisis between France and Russia related to the situation in Aleppo may have partly frozen official relations, but many in France’s establishment continue to think Russia should be seen as an ally in the Middle East.

Germany: Interdependence as Vulnerability

Stefan Meister28Stefan Meister and Jana Puglierin, “Perception and Exploitation: Russia’s Non-Military Influence in Europe,” DGAP, September 30, 2015, https://dgap.org/en/think-tank/publications/dgapanalyse-compact/perception-and-exploitation. This publication is part of an ongoing series on Russian non-military influence in Europe.

Political landscape

The annexation of Crimea and the war in Eastern Ukraine were a reality check for Germany’s Russia policy. While in the past there was a special relationship between Moscow and Berlin with hopes to change Russia through dialogue and growing economic and social interdependence, Russian aggression in Ukraine resulted in a fundamental loss of trust. The Russian disinformation campaign in Germany combined with the support for populist parties and movements marks a further stage in the degradation of the relationship. The leading role of German Chancellor Angela Merkel in the Ukraine crisis, particularly her consequent support for EU sanctions on Russia, has made Germany a main obstacle in the implementation of Russian interests in Europe and Ukraine.

At the same time, Merkel is under pressure in domestic politics because of her liberal refugee policy and tough stance on Russia. The domestic weakening of her position and the fundamental crisis of the EU open opportunities to weaken Germany’s (and the EU’s) position on Russia. The German public’s growing disenchantment with the Chancellor benefits her political opponents (and partners) with whom the Kremlin seeks to establish links and relationships. In addition, the bilateral networks, which have been established over the last fifteen years between German and Russian leaders, open opportunities for the Kremlin to influence German politics and the public debate. Such networks of influence exist inside and outside the political mainstream and are increasingly becoming tightly linked.

Under President Putin, these networks have taken on a different, more nefarious goal: to alter the rules of bilateral relations, influence German policy toward Eastern Europe and Russia, and impact EU decisions through influence networks in Berlin.

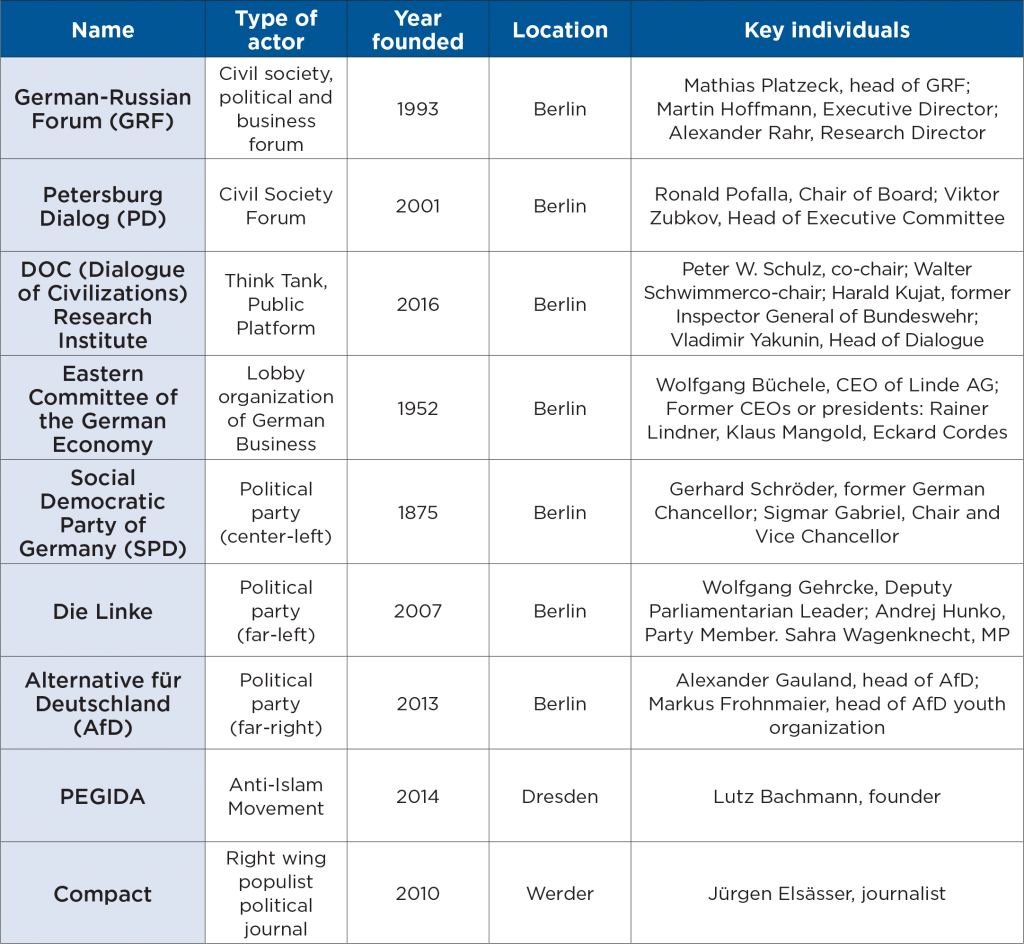

Key pro-Russian actors in Germany

Historically, German leaders since World War II have approached Russia as a special case. The recognition of the Soviet Union and later Russia as crucial to security in Europe and the desire to have relations based on trust with the Russian elite and society established deeply intertwined economic, cultural, and political networks between the two countries, particularly since the late 1960s. Under President Putin, these networks have taken on a different, more nefarious goal: to alter the rules of bilateral relations, influence German policy toward Eastern Europe and Russia, and impact EU decisions through influence networks in Berlin. These networks are purposely obscure, but still evident at the level of elite dialogue, in civil society, political parties, the economy, and the media.

Feelings of historical guilt and gratitude—because of the peaceful German unification—toward Russia are the main drivers for the moral arguments of many decision makers. There is an impression that because the Soviet Union (and Russia as its successor state) had the most victims during WW II, Germany has a moral obligation to do everything it can to ensure peaceful relations with its big neighbor. Vladimir Putin’s policy is often perceived in that historical framework, which is misleading with regard to the nature of the regime and the fundamental differences between today’s Russia and the Soviet Union.29Stefan Meister, “Russia’s Return,” Berlin Policy Journal, December 14, 2015, http://berlinpolicyjournal.com/russias-return/.

Building networks of influence

One strategy successfully employed by the Russian leadership is the recruitment of German politicians for energy projects like the Nord Stream pipeline. Shortly after leaving office, in 2005, former Chancellor Gerhard Schröder accepted a position as the board chairman of the Russian-German pipeline. Matthias Warnig, chief executive of the pipeline consortium, also headed Dresdner Bank’s operations in Russia in the 1990s and was a Stasi officer before the end of the cold war.30Mathias Warning is a prime example as a former Stasi officer who is personally linked with Vladimir Putin and involved in formal and informal economic networks in the energy, raw material, and banking sector. Dirk Banse, Florian Flade, Uwe Muller, Eduard Steiner, and Daniel Wetzel, “Dieser Deutsche genießt Putins vertrauen,” Welt, August 3, 2014, http://www.welt.de/politik/deutschland/article130829736/Dieser-Deutsche-geniesst-Putins-Vertrauen.html.

Civil society connections

These well-known examples of German-Russian connections are the tip of the iceberg. Over the last twenty years, “Russia friendly” networks of experts, journalists, politicians, and lobby institutions have been established. In particular, the German-Russian Forum (GRF) established in 1993 and the Petersburg Dialog (PD), founded by former chancellor Gerhard Schröder and President Vladimir Putin in 2001 have become key institutions for these networks. The German-Russian Forum is closely linked with, and partly funded by, German companies active in Russia.31More than 50 percent of the funding of GRF comes from German and Russian business, which includes 50 percent of the Dax (German Stock Exchange) thirty companies. See: “Frequently Asked Questions,” Deutsch-Russisches Forum, http://www.deutsch-russisches-forum.de/ueber-uns/faq#1. Board members are representatives of German politics and the economy.32“Vorstand,” Deutsch-Russisches Forum, http://www.deutsch-russisches-forum.de/ueber-uns/vorstand.“Kuratorium,” The board of trustees consists mainly of business people, often with economic interests in Russia like Bernhard Reutersbeger (EON AG), Hans-Ulrich Engel (BASF), Hans-Joachim Gornig (GAZPROM Germania), and the former head of the Russian railways, Vladimir Yakunin.33“Kuratorium,” Deutsch-Russisches Forum, http://www.deutsch-russisches-forum.de/ueber-uns/kuratorium. The GRF is responsible for the organization of the Petersburg Dialog, which is mainly funded by the German Ministry of Foreign Affairs, that aims to improve communication between the two countries. Initially, the PD was founded as an institution for civil society dialogue, but it has been established as a platform for elite dialogue (although it has been undergoing a fundamental reform process for more than a year, involving real civil society activists). It holds its meeting once a year, though its eight working groups meet more often. The German chair of the board is Ronald Pofalla, former head of the chancellor’s office and now chairman for economy, legislation, and regulation at the Deutsche Bahn. The Russian head of the executive committee is Victor Zubkov, chairman of the supervisory board of Gazprom, a former prime minister and first deputy prime minister of Russia.

The head of GRF is the former German Social Democratic Party (SPD) chair and prime minister of the Federal State of Brandenburg, Matthias Platzeck. He has made several statements to support the Russian leadership and advocate a policy of appeasement toward the Kremlin. One of Platzeck’s most controversial statements was his demand to legalize the annexation of Crimea, so “that it is acceptable for both sides,” Russia and the West.34“Russland-Politik: Ex-SPD Chef Platzeck will Annexion der Krim anerkennen,” Spiegel-Online, November 18, 2014, http://www.spiegel.de/politik/deutschland/ukraine-krise-matthias-platzeck-will-legalisierung-krim-annexion-a-1003646.html. The executive director of the GRF, Martin Hoffmann, published a plea for a restart in relations with Russia in a leading German newspaper, Tagesspiegel, in November 2014, when Russian support for the war in Eastern Ukraine was at a point of escalation. He wrote, referring to Russia, “We are losing those people who always looked toward the West…through sanctions, which are perceived as punishment by Russian society; through the rejection of a dialogue on the same eye level; through the arrogance, with which we believe [that we] hold better values; and through double standards.”35Martin Hoffmann, “Wir verlieren Russland,” der Tagesspiegel, November 18, 2014, http://www.tagesspiegel.de/meinung/plaedoyer-fuer-einen-neuanfang-der-beziehungen-wir-verlieren-russland/10992794.html. This statement represents a typical pattern of communication from “Russia friendly” groups, the so-called Putinversteher or Russlandversteher: their rhetoric links the replication of allegations of Russian propaganda with moral arguments embedded in German historical guilt with regard to WW II and typical German self-criticism.

The GRF has become a hinge between Russlandverstehern and the political, social, and economic mainstream. For example, it organized several “Dialogue of Civilization” conferences in Berlin with the former head of Russia’s railways, Vladimir Yakunin (one of the core representatives of an aggressive and intolerant conservatism in Russian elite circles). At the end of June 2016, a new think tank, the Dialogue of Civilizations (DOC) Research Institute, founded and funded by Yakunin, opened in Berlin. At the opening events, a set of Kremlin friendly experts (like former inspector general of the Bundeswehr, Harald Kujat and the former diplomat Hans-Friedrich von Ploetz) spoke; leading representatives of the GRF also were present including Matthias Platzeck, the head of the GRF.36“Platzeck Was in a First Draft Of the Agenda For the Event Named As a Speaker. DOC Research Institute Launch,” DOC Research Institute, July 1, 2016, http://doc-research.org/de/event/doc-research-institute-launch-3/.

Economic ties

The Eastern Committee of the German economy (OA) is the key lobby institution of the major German companies active in Russia and Eastern Europe. The lobby has actively argued against sanctions in the context of the Ukraine crisis since their establishment in 2014 and, more generally, for appeasement of the Kremlin. Therewith, the OA distinguishes itself from its mother organization, the Association of German Industry (BDI), whose president Ulrich Grillo supported Angela Merkel in arguing that the sanctions are necessary. Despite the sanctions and the lack of any compromise from the Russian side, the Eastern Committee organized a trip to Moscow in April 2016, in order to give representatives of leading German companies the opportunity to meet with Putin and hear arguments for the improvement of relations through a common economic space and the lifting of sanctions.“37Встреча с представителями деловых кругов ермании,” Президента России, April 11, 2016, http://www.kremlin.ru/events/president/news/51697. Even if it has lost influence in the last two years, the OA continues to try to influence decision makers to alter their position on Russia. It tries to play a crucial role in leveraging the growing differences between the SPD and Christian Democratic Union (CDU, the party of Chancellor Merkel) on policy with regard to Russia.

Political parties

Traditionally, the German Social Democrats played a central role in the conceptualization of Germany’s Eastern and Russia policy. The Ostpolitik of Willy Brandt and Egon Bahr, formulated in the 1960s, influenced the post-Soviet German Russia policy fundamentally. “Change through rapprochement” is a core formulation of this policy, and also the logic behind the partnership for modernization that was established under Foreign Minister Steinmeier in 2008. This policy has failed in light of the Ukraine conflict, which brought on an identity crisis among SPD members. The success of the New Ostpolitik, interpreted by many Social Democrats as the precondition for German unification, raised the expectation that a cooperative and integrative Russia policy would finally lead to a democratic and peaceful Russia. This long-standing foundational principle of SPD (and German) foreign policy has been proven wrong by the Putin regime. Peace and stability in Europe, at the moment, is not possible either with Russia or against it. While the SPD Foreign Minister Frank-Walter Steinmeier failed to improve the situation, despite constant offers of dialogue with the Kremlin, he had to find a balance between the tradition of a cooperative Russia policy as demanded by his party and the reality of Putin’s power politics. Therefore, in a strategy speech in April 2016, he argued for a “double dialogue” with Russia: “Dialogue about common interests and areas of cooperation but at the same time an honest dialogue about differences.”38“Rede von Außenminister Frank-Walter Steinmeier beim Egon-Bahr-Symposium,” Auswaertiges Amt, April 21, 2016, http://www.auswaertiges-amt.de/DE/Infoservice/Presse/Reden/2016/160421_BM_EgonBahrSymposium.html.

In the past, it was primarily the older generation of the SPD who argued for compromise with Russia (e.g., former Chancellor and Putin confidant, Gerhard Schröder, or the recently deceased former Chancellor Helmut Schmidt). Today, however, a new generation within the mainstream party supports a pro-Kremlin policy that is often at odds with German and EU policy. The current SPD-Chair and Vice Chancellor Sigmar Gabriel questions Merkel’s position on the Russian leadership. In October 2015, at a meeting with Putin in the Kremlin, Gabriel supported a closer German-Russian cooperation through the extension of the Nord Stream natural gas pipeline, dubbed Nord Stream 2. According to a transcript of the meeting published by the Kremlin, Gabriel offered to ensure approval of the project in Germany, while circumventing EU regulations and weakening the sanctions regime.39“Meeting with Vice-Chancellor and Minister Of Economic Affairs and Energy Of Germany Sigmar Gabriel,” President of Russia, October 28, 2015, http://en.kremlin.ru/events/president/news/50582. Nord Stream 2 would double Russian gas flows to Germany by potentially allowing Russia to cut off Ukraine from gas supplies while keeping gas flowing to Europe uninterrupted. It questions EU policy of increasing diversification of gas supply in the context of the Energy Union.40Stefan Meister, “Russia, Germany, and Nord Stream 2 – Ostpolitik 2.0?,” Transatlantic Academy, December 7, 2015, http://www.transatlanticacademy.org/node/874.

Furthermore, Gabriel argued several times in official speeches for the abolition of economic sanctions toward Russia.41“Festrede von Bundesminister Sigmar Gabriel, Deutsch-Russisches Forum,” Deutsch-Russisches Forum, March 17, 2016, http://www.deutsch-russisches-forum.de/festrede-von-bundesminister-sigmar-gabriel/1510. Foreign Minister Steinmeier not only supports a double dialogue but also the gradual lifting of sanctions on Russia, if there are small steps of improvement in Eastern Ukraine. He presented this idea at a conference of the German-Russian Forum in Potsdam in the end of May 2016.42“Rede von Außenminister Frank-Walter Steinmeier beim Deutsch-Russischen Forum/Potsdamer Begegnungen,” Auswaertiges Amt, May 30, 2016, https://www.auswaertiges-amt.de/DE/Infoservice/Presse/Reden/2016/160530_BM_DEU_RUS_Forum.html. Steinmeier is much influenced by his party’s base and by his party colleague Gabriel, who is also minister of the economy. All of these statements by Gabriel and Steinmeier involve the deterioration in relations with Russia within the SPD, but they are also a reflection of the fact that Russia is a hot topic for German society and Germany’s approach to Russia will likely be an important policy issue in the federal elections in autumn 2017. Also, Gerhard Schröder still advises the SPD leadership on Russia, as Steinmeier was formerly the head of his chancellery office.

Besides the SPD, two opposition parties—the post-communist Die Linke and the far-right populist party Alternative für Deutschland (Alternative for Germany or AfD)—cultivate contacts with Russia and vice versa. The deputy parliamentarian leader of Die Linke in the Bundestag, Wolfgang Gehrcke constantly argues that the United States played the crucial role in the Ukraine conflict.43“Linkspartei: Westen will Russland in einen Krieg treiben,” Sputnik, January 21, 2015, https://de.sputniknews.com/politik/20150121/300712540.html. Gehrcke travelled with his party colleague Andrej Hunko to the separatist-controlled regions in Eastern Ukraine in February 2015. Both delivered relief aid and met the leaders of the self-described “Donetsk People’s Republic” (DNR). In the Bundestag, Gehrcke and Hunko argue for closer cooperation with Russia,44Gehrcke argued several times for a dissolution of NATO and for lifting sanctions on Russia: Pressemitteilung von Wolfgang Gehrcke, “Sanktionen gegen Russland beenden,” Linksfraktion, December 14, 2015, https://www.linksfraktion.de/presse/pressemitteilungen/detail/sanktionen-gegen-russland-beenden/; Or in an interview with Sputnik: “Linke-Abgeordneter Gehrcke: Russland-Sanktionen aufheben, die Nato auflösen,” Sputnik, July 7, 2016, https://de.sputniknews.com/politik/20160707/311231059/gehrcke-russland-sanktionen-nato.html. and they recently organized a conference on Eastern Ukraine involving individuals linked to the former Ukrainian President Victor Yanukovych.45Pressemitteilung Andrej Hunko, “Dokumentation des Ukraine-Fachgesprächs zu Minsk II am 8. Juni 2016 im Bundestag,” Linke, July 8, 2016, http://www.andrej-hunko.de/presse/26-videos/3175-dokumentation-fachgespraech-minsk-ii.

Alexander Gauland, the head of AfD Brandenburg and deputy speaker of his party in the Bundestag, visited the Russian embassy at the end of November 2014; he argues for a regular exchange with Russian officials and improvement in relations with Russia. In April 2016, the head of the AfD youth organization, Markus Frohnmeier, met with Russian Duma MP and head of the Commission for International Affairs of the Kremlin-backed party United Russia, Robert Schlegel.46Melanie Amann and Pavel Lokshin, “German Populists Forge Ties with Russia,” Spiegelonline, April 27, 2016, http://www.spiegel.de/international/germany/german-populists-forge-deeper-ties-with-russia-a-1089562.html. Schlegel’s task in this commission is to cultivate contacts with friendly parties abroad. In the past, he led the press office of the pro-Kremlin youth organization Nashi. Frohnmeier and Sven Tritschler, the co-head of the AfD’s youth wing, have sought to establish a partnership with the Young Guard, the youth wing of the United Russia party. Schlegel argued, with regard to AfD, that this is a “constructive political movement” in Europe, “which supports Russia and argues for an abolishment of sanctions.”47“Российские депутаты налаживают связь с европейскими коллегами,”Izvestia, April 22, 2016, http://izvestia.ru/news/611013. In one of its few foreign policy resolutions, the AfD argued, in November 2015, for the abolishment of all sanctions directed against Russia.48“Resolution ‘Außenpolitik’ der Alternative für Deutschland,” Alternative fuer Deutschland, November 29, 2015, http://alternativefuer.de/wp-content/uploads/sites/7/2015/12/Resolution-Au%C3%9Fenpolitik.pdf. AfD was campaigning in local elections with flyers in Russian, targeting German Russians and Russian-speaking minorities. Its success in local elections in 2016 —in Saxony-Anhalt (24.3 percent), Mecklenburg-Vorpommern (20.8 percent), and Berlin (13.8 percent)—puts pressure on Angela Merkel for her refugee policy and increases the criticism of her own party (CDU) and its sister party, the Christian Social Union, in the lead up to the federal elections in autumn 2017.

Networks, Platforms, and Media

Similarly to Die Linke and AfD, the anti-establishment and anti-Islam movement, PEGIDA, describes Putin’s Russia as an alternative to US influence and Brussels bureaucrats. It is difficult to prove direct links between PEGIDA and Russian officials. However, Russian flags are present at demonstrations of PEGIDA and its offshoots, and the Russian media provide prominent coverage of PEGIDA demonstrations. For example, RTdeutsch regularly presents live stream coverage of PEGIDA rallies. AfD, PEGIDA, and the neo-fascist party National Democratic Party (NPD) are linked, through their connections with Russian political and affiliated groups, with right-wing Russian and European networks. Former NPD Chair Udo Vogt participated in a congress of new right and right-wing parties in St Petersburg in March 2015 to discuss traditional values in Europe.49“NPD auf Einladung von Putin-Freunden in St. Petersburg,” der Tagesspiegel, March 22, 2015, http://www.tagesspiegel.de/politik/rechtsextremisten-npd-auf-einladung-von-putin-freunden-in-st-petersburg/11540858.html, accessed October 10, 2016. The main organizer of the event was the Russian nationalist party Rodina, which is linked with Dimitri Rogozin, deputy prime minister responsible for the military-industrial complex and a strong anti-Western propagandist within the Russian leadership.

Russian media like Sputnik, RT, and their German wing RTdeutsch are active in Germany. They cooperate closely with journalists and internet media, who are critical of the current US-dominated international system, such as Jürgen Elsässer and his journal Compact. Elsässer is a conspiracy theorist and a popular guest on Russian state and foreign media. He distributes Russian state propaganda through his media outlets and public presentations and supports the AfD. On the website of Compact, he reports on PEGIDA demonstrations and condemns the “NATO-Fascists” in Ukraine.50Regierung/Maidanbehörden verlieren Kontrolle über Süden und Osten,” Compact Online, March 1, 2014, https://www.compact-online.de/ukraine-volksaufstand-gegen-putsch-regierung-maidanbehoerden-verlieren-kontrolle-ueber-sued-und-osten/; Oder, “NATO-Faschisten holen sich blutige Nase auf der Krim,” Elsässers Blog, March 1, 2014, https://juergenelsaesser.wordpress.com/2014/03/01/nato-faschisten-holen-sich-blutige-nase-auf-der-krim/. In 2012 and 2013, Elsässer organized a series of so-called compact sovereignty conferences, together with the Kremlin-linked “Institute for Democracy and Human Rights” (IDHR) in Paris. The IDHR is part of the Kremlin’s counteroffensive against democracy and the human rights policies of the West.

Conclusions

Russian influence in Germany takes place on three levels using: 1) pro-Kremlin networks, which were mainly established over the past fifteen years, and which support a policy of appeasement with regard to the current Russian regime; 2) parties and populist movements at the right and left margins of the political spectrum, but also the mainstream political parties in the Bundestag; and 3) Russian foreign media, which is often linked to these pro-Russian groups through social networks. With the Ukraine crisis, these three elements became increasingly intertwined and continue to attempt to penetrate German society, politics, and the public discourse.

These attempts to influence German and EU-policy toward Russia are countered by the consequent approach of Chancellor Merkel and other elements of the German political system, for whom Russian actions in Ukraine were a reality check. The Kremlin’s goals are to undermine and question the approach of the current German leadership on Russia, legitimize its policy in Ukraine through these networks in the EU, split European societies and transatlantic unity, while fueling existing anti-US, anti-EU, and anti-establishment sentiments within German society. This intensifies the polarization of the German discourse on Russia and weakens a common German and EU policy toward the Putin system. From the Kremlin’s perspective, the vulnerable points in Germany include the German Social Democrats with their culture of compromise and accommodation toward Russia; a generally pacifistic society, which feels guilt toward the Soviet Union/Russia with regard to WW II; as well as the interconnected political and economic networks.

In the campaign for the next federal elections in Germany, Russia will play a prominent role.

In the campaign for the next federal elections in Germany, Russia will play a prominent role. Merkel’s current coalition partner and campaign competitor, the SPD, will try to distance itself from her policies, and other parties like Die Linke and AfD will question current Russia policy in order to undermine Merkel’s position. Putin is described, in the literature of right-wing populist groups and parties, as an alternative to US influence in Europe and “Gayropa.” The Kremlin will try to use its access to these parties and groups to strengthen its positions and weaken support for Merkel’s current approach. At the same time, it uses parliamentarians from mainstream and populist parties to legitimize its policy through their visits to occupied territories or as election observers in fake elections or referendums. But even if Angela Merkel is not re-elected as German chancellor, the fundamental loss of trust and damage to bilateral German-Russian relations will not disappear. Undermining international law and institutions, as well as following a strategy of controlled destabilization in the common neighborhood as a policy stands in direct conflict with the interests and principles of German policy.

United Kingdom: Vulnerable but Resistant

Neil Barnett

Political landscape

The United Kingdom (UK) is less vulnerable than most European states to Russian subversion and penetration. It lacks a common Slavic or Orthodox heritage with Russia, it has no legacy of communist rule, and its population has traditionally been uninterested in extremism of the left or right. In addition, there is a deep-seated wariness of Russia in British government institutions and in society at large, owing to the memory of imperial rivalry in Central Asia and to decades of military, intelligence, and political confrontation in the Cold War. Recent Russian actions, such as the 2006 murder of Alexander Litvinenko, allegedly ordered by Russian President Vladimir Putin, and Russia’s military intervention in Ukraine have reinforced British suspicions.

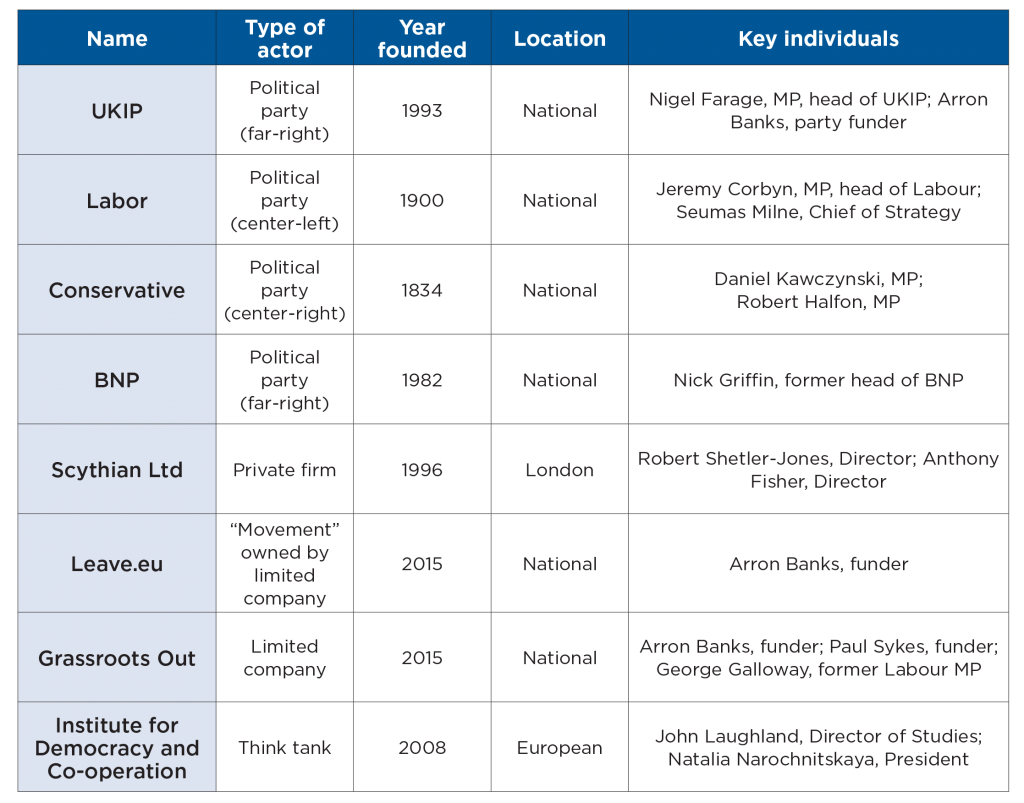

Still, in recent years, the rise of disruptive populist forces on the right and the left, as most obviously demonstrated by Brexit, provides an opportunity for Russia to gain a foothold in British politics. The electorate’s decision to leave the European Union in June 2016 suited the Kremlin, because it weakened the EU overall and made exits by other states more likely. A fragmented Europe makes it far easier for Russia to dominate individual states and to weaken the Europe-US relationship. In particular, the UK’s nuclear deterrent and its position as a leading hawk on the question of EU sanctions on Russia mark it out as a target for Russian “active measures.”51“Active measures” is the term used by Russian intelligence organizations to describe actions intended to manipulate an adversary into a particular course of action. It can include disinformation, destabilization, and aggressive military posturing among other measures. One of the aims of “active measures” is “reflexive control,” the art of making an adversary do something that is not in his interests, but is in the interests of Russia.

. . . [T]he rise of disruptive populist forces on the right and the left . . . provides an opportunity for Russia to gain a foothold in British politics.

The referendum outcome now offers further possibilities for division and fragmentation as friction builds over when and how Britain leaves the bloc. Popular concern over immigration forms a part of this divisiveness. Before the referendum campaign, the UK Independence Party (UKIP) avoided directly inflammatory rhetoric about immigration. During campaigning in 2016, UKIP’s line on immigration became markedly more aggressive, bringing the party closer to radicals like the French National Front and the German AfD. The leader of UKIP, Nigel Farage, also moved the party’s foreign policy closer to Russia, criticizing the EU’s sanctions regime and publically expressing admiration for the Russian president.

The governing Conservative Party under Theresa May is committed to NATO and to the Atlantic alliance, but there are pockets of Russian-related money and influence within the party, which are mainly the result of a failure to properly regulate sources of party funding.52The law covering political party funding prohibits contributions from non-British companies or individuals. However, if a company is incorporated in the EU and carries out business in the UK, then under the law its beneficial ownership is immaterial. The ‘regulated entities’ (i.e. the parties receiving the funds) are required to check that these conditions are met, and in practice the Electoral Commission (which regulates elections and political funding) rarely examines the ultimate source of funds itself. Specific examples of UK companies with politically-connected Russian owners (or owners closely associated with such people) this are described in this paper. Equally, in recent decades the standards of behavior and integrity that the public expects from politicians have declined, with voters now accepting a degree of cupidity from current and former political leaders who, by way of illustration, open international consultancy firms after leaving office (former Prime Minister Tony Blair’s and former Secretary of State Peter Mandelson’s international consultancy operations are striking examples).53Blair’s company, Tony Blair Associates (TBA), counted several repressive regimes among its clients, including Kazakhstan and Azerbaijan, while Lord Mandelson’s company Global Counsel uses a loophole in Independent Parliamentary Standards Authority rules to conceal the company’s Russian and Chinese clients. Note that Blair announced the closing of TBA in September 2016.

Finally, Labour, the main opposition party, is now led by a hard leftist, Jeremy Corbyn. He and his close advisers (and the “Momentum” movement that supports him) follow a socialist agenda that is reminiscent of former presidential candidate Bernie Sanders in the United States. Under Corbyn’s leadership, the party’s positions (declared or hinted at) are anti-EU, anti-nuclear weapons, anti-Israel, and skeptical toward NATO. They are openly warm toward both Russia and Iran, in part because these two states offer the most determined opposition to a Western system that Corbyn and his fellow travelers regard as corrupt and exploitative. In return, Russia openly supports Corbyn: when he was elected Labour leader, the Russian ambassador in London, Alexander Yakovenko, said he had a “democratic mandate” for “opposition to military interventions of the West, support for the UK’s nuclear disarmament, conviction that NATO has outstayed its raison d’etre with the end of the Cold War, just to name a few.”54Peter Dominiczak and Matthew Holehouse, “Russian Ambassador Praises Jermy Corbyn’s Victory,” Telegraph, September 21, 2015, http://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/politics/Jeremy_Corbyn/11881100/Russian-ambassador-praises-Jeremy-Corbyns-victory.html.

Key pro-Russian actors in the UK

The most openly pro-Russian political party in the UK is UKIP. The party has only one member of parliament (MP), Douglas Carswell, owing to the first-past-the-post electoral system, but post-Brexit, its influence and potential is far greater than that number would suggest. In the 2015 general election, UKIP secured 12.6 percent of the popular vote (3.88 million votes)55“Elections 2015: Results,” BBC News, accessed October 24, 2016, http://www.bbc.com/news/election/2015/results. and yet has just one of the 650 House of Commons seats in Westminster. The Brexit vote has drawn attention to this disparity between UKIP’s support and representation by showing that the party’s central policy appeals to a majority of the electorate. As a result, UKIP now has an opportunity to capitalize on the vote to capture seats in pro-Brexit districts, assuming the party can overcome its indiscipline and internal squabbles. UKIP campaigned for Brexit together with the Leave.eu and Grassroots Out campaigns of Arron Banks (the Bristol-based insurance entrepreneur who made the largest financial contribution to the Out campaign).56Neil Barnett, “Who Funded Brexit?,” American Interest, July 26, 2016, http://www.the-american-interest.com/2016/07/26/who-funded-brexit/. In the immediate post-Brexit period, Banks spoke of launching a new, more professional party that would corral disaffected voters under an anti-EU, nationalist agenda.57Robert Booth, Alan Travis, and Amelia Gentleman, “Leave Donor Plans New Party to Replace UKIP-Possibly Without Farage In Charge,” Guardian, June 29, 2016, https://www.theguardian.com/politics/2016/jun/29/leave-donor-plans-new-party-to-replace-ukip-without-farage.

The Labour party under Jeremy Corbyn is deeply divided. Its leadership adheres to old-fashioned revolutionary politics, with pro-Russian, pro-Iranian leanings, and extensive links to Hamas and other terrorist groups. Corbyn officially campaigned to remain in the EU, but in a reluctant manner that suggested his real sympathies lay with Brexit, which led some to allege that he “sabotaged” the remain campaign.58Phil Wilson, “Corbyn Sabotaged Labour’s Remain Campaign. He Must Resign,” Guardian, June 26, 2016, https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2016/jun/26/corbyn-must-resign-inadequate-leader-betrayal. It is important to remember, however, that Corbyn’s leadership is precarious and that his pro-Moscow sentiments are not widely shared in the parliamentary Labour party. He owes his position as head of the party to recent governance changes that give the power to elect the party leader to paid-up members, rather than the Parliamentary party. This means that Corbyn does not command the support of his own MPs or of many Labour voters, and indeed he is deeply unpopular throughout the country.59A survey by Survation reported in September 2016, for example, “has shown the Prime Minister’s net favourability rating at +33.6, while the Labour leader languishes on -30.7”. See: Emillio Casalicchio, “Theresa May Holds Massive Popularity Lead Over Jermy Corbyn, Poll Shows,” Politics Home, September 4, 2016, https://www.politicshome.com/news/uk/politics/opinion-polls/news/78626/theresa-may-holds-massive-popularity-lead-over-jeremy. In other words, a Trotskyite faction has successfully taken over the Labour party de jure, but de facto the party’s MPs60In June 2016, 80 percent of Labour MPs supported a no-confidence vote against Jeremy Corbyn. He nonetheless won the ensuing leadership vote, because it is party members, not MPs, who choose the party leader. See: Anushka Asthana, Rajeev Syal, and Jessica Elgot, “Labour MPs Prepare for Leadership Contest After Corbyn Loses Confidence Vote,” Guardian, June 28, 2016, https://www.theguardian.com/politics/2016/jun/28/jeremy-corbyn-loses-labour-mps-confidence-vote. and voters remain overwhelmingly moderate and uninterested in Corbyn’s brand of radical, pro-Russian politics.

In the ruling Conservative Party, as described in more detail in the following section, there are several recent indications of substantial donations with direct links to Russia. Overall, however, there is little to suggest that Theresa May and her cabinet are diverging from long-held policies of conventional and nuclear deterrence, NATO membership, and the transatlantic alliance. Indeed, her government is likely to show greater commitment to these policies than her predecessor, David Cameron.61Neil Barnett, “The UK Returns,” American Interest, August 15, 2016, http://www.the-american-interest.com/2016/08/15/the-uk-returns/.

There are a small number of Conservative MPs with ardently pro-Russian views, the most obvious of whom is the backbench MP for Shrewsbury, Daniel Kawczynski. John Whittingdale, the former secretary of state for culture, media and sport, also has long-standing links to a questionable figure from the former Soviet Union, Dimitri Firtash, although he does not lobby for Russia in the manner of Kawczynski.

In addition, there are some renegade and marginal pro-Russian figures. The most outspoken of these is George Galloway, a former Labour MP who was expelled from the party in 2003 for bringing it into disrepute.62Matthew Tempest, “Galloway Expelled from Labour,” Guardian, October 23, 2003, https://www.theguardian.com/politics/2003/oct/23/labour.georgegalloway. He subsequently became the sole MP in a fringe leftist party, Respect, but lost his Parliamentary seat in the 2015 election. Galloway was also a part of the Grassroots Out campaign.

The far-right British National Party (BNP) is openly pro-Russian, but owing to its marginal status, it is not covered in any depth here. Nick Griffin, the former leader of the BNP, told a crowd of two hundred Russian nationalists and their European sympathizers in 2015:63Courtney Weaver, “To Russia with Love, From Europe’s Far-Right Fringe,” Financial Times, March 22, 2015, http://www.ft.com/cms/s/0/556ed172-d0b9-11e4-982a-00144feab7de.html#ixzz4HPm0ukx5. “Every European nation has had its time leading Europe and indeed the world. The Greeks. The Romans. The Spanish. The French. The Germans. The British. Every great people – except the Russians. And now it becomes historically Russia’s turn.” The BNP (like other British far right groups) has no MPs and only fielded eight candidates in the last election.

Building networks of influence

In the ruling Conservative party, Russian influence is superficial and lacks critical mass. Nonetheless, there are notable cases of individual MPs and other influential actors who have links with Russian interests.

Daniel Kawczynski has for some time been an outspoken Parliamentary advocate of Saudi Arabia, earning the sobriquet “the honourable member for Riyadh Central.”64Andy McSmith, “Andy McSmith’s Diary: The Honourable Member for Riyadh Central,” Independent, June 24, 2014, http://www.independent.co.uk/news/uk/politics/andy-mcsmiths-diary-the-honourable-member-for-riyadh-central-9560775.html. In recent years, he has developed the same enthusiasm for Russia. For example, in January 21, 2016, Kawczynski tabled a written Parliamentary question to the Home Office on the Litvinenko Inquiry. He appeared unconcerned by state-sponsored assassination on the streets of London and instead questioned the cost of the Inquiry:65“Litvinenko Inquiry: Written Question – 23589,” United Kingdom Parliament: Publications and Records, January 21, 2016, http://www.parliament.uk/business/publications/written-questions-answers-statements/written-question/Commons/2016-01-21/23589/. “what the cost was to the public purse of the public inquiry into the death of Alexander Litvinenko; and what the average cost was to the public purse of inquiries into suspicious deaths undertaken by coroners over the last three years.” On other questions, he has sought assurances that the UK will redouble efforts to cooperate with Russia in Syria, will remove sanctions, and, more generally, work on “improving collaboration on defense affairs” with Russia. He has written op-eds for RT and is a frequent guest on its programs. In May 2016, Kawczynski visited Moscow, where he told RT:66“‘Russia No Pariah, But Strategic Partner to the West’ – British MP to RT,” Russia Today, May 18, 2016, https://www.rt.com/news/343490-uk-kawczynski-russia-sanctions/. “I, for one, believe that our government isn’t doing everything appropriately to try to smooth relations with Moscow.” He also lobbies at the political level, in private in his native Poland, for better relations with Russia.

There are also several sources of Russia-related party funding. For example, in August 2016, a Labour MP wrote to the prime minister, Theresa May, to question the provenance of a £400,000 party donation made by Gerard Lopez of Rise Capital, a fund that specializes in Public-Private Partnership infrastructure deals in Russia.67Holly Watt, “May Must Explain Tory Donor’s Links to Russia, Says Labour MP,” Guardian, August 27, 2016, http://www.theguardian.com/politics/2016/aug/27/may-must-explain-tory-donors-links-to-russia-says-labour-mp. This implies that while such donations may formally comply with Electoral Commission regulations, there may be a quid pro quo with Russian business partners to channel political donations.

In January 2016, the Conservatives received £100,00068“Conservative and Unionist Party, Cash (C0242166): Donation Summary,” The Electoral Commission, accessed on October 24, 2016, http://search.electoralcommission.org.uk/English/Donations/C0242166 from Global Functional Drinks Limited,69The company’s 2016 Annual Return shows all 1,000 shares owned by the Swiss parent, Global Functional Drinks AG. a UK subsidiary of the Swiss firm, Global Functional Drinks AG,70Global functional drinks AG is a Swiss-based company. http://gfdrinks.ch/?switch#social. which is, in turn, controlled by Oleg Smirnov’s SNS Group, one of the leading Russian tobacco firms.71A 2013 article in Fortune magazine, reproduced on the SNS website, carries the following text: “In 2011 – after a spell as the sole Russian distributor of Red Bull – SNS acquired a 75 percent stake in the domestic Global Functional Drinks company (since 2012 SNS is the 100 percent stakeholder in GFD) and has turned its attention to promoting, marketing, and distributing its middle-market Tornado Energy drinks.” See: “SNS in New July Issue Of Fortune Magazine,” SNS Group of Companies, July 22, 2013, http://en.sns.ru/group/news_company/2013/4219/.