World powers have spent years trying to save the JCPOA. That’s more time than it was fully implemented and why they need a reset.

In February 2022, only days after the Russian invasion of Ukraine, German Chancellor Olaf Scholz delivered a speech saying the world was “living through a Zeitenwende,” or a watershed moment in history. The tectonic plates of the existing geopolitical order have been shifting ever since. World powers tried in vain to insulate the Iran nuclear file from those headwinds—finding comfort in the precedent of 2014, when Russia invaded Crimea and the Iran nuclear talks still produced a result—but it didn’t work. Since September 2022, negotiations with Tehran have remained on ice. Thus, the United States and its European allies should also recognize the moment as a Zeitenwende with respect to the Islamic Republic. But this doesn’t have to be a negative, as it represents an opportunity to reset transatlantic Iran policy more sustainably.

A changed landscape and calculus

For two years, the Joe Biden administration has sought to recreate a geopolitical, political, and technical reality of Iran’s nuclear program that does not exist anymore. Russia’s invasion of Ukraine has been the biggest land war on European soil since 1945. That has fundamentally altered this international context. It has also put to bed the illusion that the original P5+1—Britain, China, France, Germany, Russia, and the United States—can effectively coerce Tehran into providing a “yes” on diplomacy. Tehran now has more leverage over Moscow by becoming its military supplier in Ukraine, which was not the case in 2015, making Russia less willing to pressure the Islamic Republic on the nuclear file. Iran will exploit the lack of international consensus this creates.

The Islamic Republic has been uninterested in reviving the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA) on reasonable terms for well over a year. Supreme Leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei has spoken repeatedly about how the globe is on the brink of a new, multipolar world order, where the United States is isolated. He has also argued that there will be a “transfer of political, economic, cultural, and even scientific power from the West to Asia.” The recent deal brokered by China to normalize relations between Iran and Saudi Arabia fits perfectly into Khamenei’s ideology looking eastward. It may even reinforce the Iranian establishment’s reasoning that it can muddle along without a JCPOA.

It is this posture that has animated Iranian strategic thinking and undergirded its fateful decision in 2022 to provide materiel to Russia. Khamenei has married his goal of a resistance economy neutralizing sanctions with this mindset. There has even been resistance to an interim nuclear deal—with Tehran rejecting one multiple times since 2021—and it appears more interested in using the diplomatic process as cover to build out its nuclear program rather than an agreement.

There is also a historic movement for freedom currently taking shape in Iran. The US often has an aversion to supporting protesters in Iran, given the controversial brand of regime change that followed the US invasions of Afghanistan and Iraq. However, it’s this very restraint—while offering sanctions relief to revive the JCPOA—which is ironically a form of intervention itself. It risks impairing an Iranian struggle for democracy by empowering the clerical elite. Iranians already view attempts to resource the regime through economic relief as an external interference in a domestic political contest.

More diplomacy, more escalation

Tehran has been emboldened to continue to test international red lines by the absence of nuclear deterrence. While the diplomatic door remained open for two years, the regime made its greatest advances. Between May 2018 and January 2021, when the Donald Trump administration was pursuing its maximum pressure policy, Iran only carefully, incrementally, and reversibly advanced its nuclear program beyond the JCPOA limits. In fact, Iranian officials admitted Tehran waited for a year before violating the agreement. This was especially the case since, in January 2020, the US demonstrated its willingness to use force when it launched a strike killing the Quds Force Commander Qasem Soleimani—reinforcing deterrence on multiple fronts.

That changed after the November 2020 election results came in, with the system calculating that it could exploit the stated willingness of the incoming Biden presidency to return to mutual compliance with the JCPOA. This, along with the assassination of Mohsen Fakhrizadeh (the father of Iran’s past nuclear weapons program), set the table for considerable escalation mandated by Iranian law: Initially restarting uranium enrichment to 20 percent, then 60 percent as negotiations to revive the JCPOA started, and finally (discovered most recently) 83.7 percent; Halting implementation of the Additional Protocol; Producing uranium metal; and Tehran also experimented with advanced centrifuges, which provided it with irreversible knowledge gains.

What were once ring-fenced, reversible Iranian steps during the maximum pressure campaign morphed into more aggressive advances, as Washington prioritized the pursuit of a return to mutual compliance with the 2015 accord above all else. That, coupled with US priorities of a pivot to Asia, the hasty US withdrawal from Afghanistan, and a lack of interest in meaningfully countering Iran in the region (apart from a few targeted strikes on its terror proxies, which were absorbable for the system as they did not target Iranian territory), likely increased the establishment’s appetite for risk. Furthermore, the degree of sanctions relief required to revive the JCPOA at this stage is not worth its expiring sunset clock and the reduced breakout timeline, given its irreversible nuclear advances.

A reset

Given these realities and trendlines, the United States and Europe urgently need a new Iran policy. And the way to begin would be for either Britain or France, as permanent members of the UN Security Council, to invoke the snapback sanctions mechanism under UN Security Council Resolution 2231. This move would accomplish a few objectives simultaneously. It would shatter the Iranian decision-making calculus, which begot escalation under the assumption that the United States and Europe would always remain at the negotiating table no matter what steps Tehran takes.

It would also restore permanency to the fast shrinking international arms restrictions architecture on Iran. In October 2020, the conventional arms embargo lapsed, and that sunset provided legal cover for Tehran and Moscow to engage in drone proliferation in Ukraine. With it no longer on the books, Russia is contemplating providing more advanced fighter jets to Iran like the Sukhoi Su-35. Even more problematic is the upcoming sunset under Resolution 2231, which lifts restrictions on Iran’s missile program in October. It is this very clause which Washington and its allies are relying upon to hold Iran and Russia accountable for arms transfers in Ukraine, as the limitations also apply to drones as complete delivery systems listed in the Missile Technology Control Regime.

Washington and its allies should outline a policy with multiple pillars. The first should involve spearheading a multilateral sanctions campaign against the Islamic Republic coupled with aggressive enforcement to deny it resources. A crackdown on regime-linked businessmen and their families using Western jurisdictions to profit off the systemic corruption in Tehran will also be necessary to sharpen the choices of the Iranian elite and potentially encourage defections.

The second should be diplomatic isolation. While the United States and its allies have undertaken a series of steps to do just that—for instance, removing Tehran from the UN Commission on the Status of Women in December 2022—there is more that can be done. This should start with G7 countries downgrading their diplomatic ties with the Islamic Republic, which will signal to Iranian decision-makers that it will no longer be business as usual.

The third is the development of a credible military threat. Biden administration officials should be more specific that the military option is on the table, as former US officials have advised. Biden’s Democratic predecessor, Barack Obama, explicitly stated as such. However, President Biden has been vaguer and shies away from specific mentions, only responding that he would “if it was the last resort,” declining to even utter the words “military” or “force.”

Costs for crossing red lines should be broadcast publicly and privately. US officials must also halt the practice of immediately distancing American officials from sabotage operations in Iran—preserving strategic ambiguity as Israeli voices have suggested—and cease providing news outlets with the impression that it is not ready to act militarily against Iran. Iranian policymakers take note of this hesitancy and Washington must correct that perception.

This line of effort should continue with the United States, Israel, and other allies engaging in joint military exercises (like Juniper Oak this past January) and practicing striking hardened targets. Tehran digests such military signaling carefully and shows of force have an impact on its policies, as it decided to suspend its nuclear weapons program in fall of 2003, just months after the US invaded Iraq, fearing Washington was next eyeing the Islamic Republic.

As others have counseled, the US government should likewise transfer the GBU-57 Massive Ordnance Penetrator to Israel, which could pierce underground facilities like Fordow, as well as lease it a B-2 bomber as a delivery vehicle. This would reinforce deterrence, as Tehran fears an attack from Israel more than the United States. This can be seen in Iranian targeting US bases in retaliation for Israeli strikes on Iranian interests in Syria.

The US debate over Iran has often presented a false dichotomy between war and diplomacy. But there are variations in between, and a strike on an Iranian military or nuclear facility does not necessarily guarantee a regional war. In fact, the targeted killing of Soleimani did not produce a large-scale war. In this context, Washington and its allies should consider launching operations targeting military bases in Iran in retaliation for its provision of arms to Russia for use against Ukraine. This would influence an appraisal that the costs of such transfers outweigh the benefits and could help reinforce deterrence on the nuclear file as well.

In the end, the US and its European allies need a new Iran policy. The nostalgia over the JCPOA is detached from the agreement’s sunset schedules and the altered international environment. Viewing Iran policy solely through the lens of enrichment levels, monitoring, and verification without widening the strategic aperture to understand the second- and third-order effects of bankrolling a pariah government benefits Tehran.

As a US defense official recently warned, “we are now at a point where Iranian threats are no longer specific to the Middle East, but a global challenge.” This is why the focus should now turn to comprehensively denying Tehran resources, deterring its malign behavior, and supporting the Iranian people. Those who argue JCPOA-like diplomacy is the most durable policy ignore the tortured history of the last seven years, when world powers have spent more time trying to save that agreement than it was ever fully implemented.

Jason M. Brodsky is the policy director of United Against Nuclear Iran (UANI). His research focuses on Iranian leadership dynamics, the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC), and Iran’s proxy and partner network. Follow him on Twitter: @JasonMBrodsky.

Further reading

Tue, Dec 8, 2020

A history of continuity in Iran’s long nuclear program

IranSource By Sina Azodi

Iran’s interest in developing a nuclear deterrent is often attributed to the Islamic Republic. However, in reality, this interest predates the 1979 revolution and reflects a deep-seated desire for national prestige and development, as well as a need to deter regional rivals.

Thu, Mar 2, 2023

Iran’s nuclear program is advancing. So too should negotiations.

IranSource By

Regardless of whether the 84 percent enriched particles were accidental, this incident underscores the increased challenge in discerning Tehran’s nuclear intentions and the growing proliferation risk of Iran’s rapidly expanding nuclear program.

Thu, Jan 19, 2023

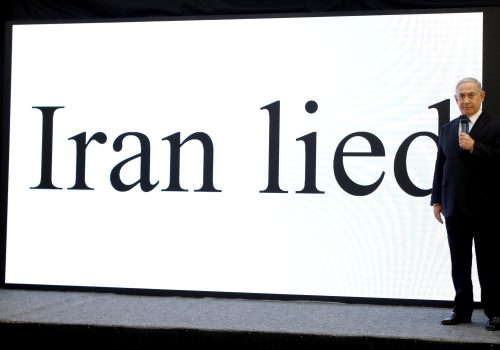

Netanyahu’s Iran policy is expected to fail—again

IranSource By Danny Citrinowicz

The biggest problem that Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu has today is the fact that he will have a tough time rallying the Joe Biden administration.

Image: International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) Director General Rafael Grossi speaks on during a news conference with Head of Iran's Atomic Energy Organization Mohammad Eslami as they meet in Tehran, Iran, March 4, 2023. Majid Asgaripour/WANA (West Asia News Agency) via REUTERS