Iran’s nuclear program is advancing. So too should negotiations.

Iran’s nuclear program made headlines again on February 20 after Bloomberg reported that the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) detected uranium particles enriched to 84 percent at an Iranian facility. Unsurprisingly, Iran denied that it has ratcheted up enrichment to that level, which is just short of the 90 percent generally considered weapons grade. A February 28 report by the IAEA confirmed the presence of 84 percent enriched uranium, but only said that discussions with Iran over the incident are ongoing and that Iran is not stockpiling uranium enriched to that level.

Although the spike could be an accident, as Iran claims, Tehran has recently threatened to pursue 90 percent enrichment to build leverage over the United States. The particles could indicate that Iran is experimenting with near-weapons grade enrichment without informing the agency, as required, to increase pressure or shorten the path to nuclear weapons down the road.

Regardless of whether the 84 percent enriched particles were the accidental product of Iran reconfiguring its centrifuges or produced by design, this incident underscores the increased challenge in discerning Tehran’s nuclear intentions and the growing proliferation risk of Iran’s rapidly expanding nuclear program. This is one of several actions that Iran has taken to advance its nuclear program over the past six months while negotiations to restore the 2015 nuclear deal, known as the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA), remain stalled.

This near-weapons-grade activity should raise alarm bells in the United States and Europe over the urgent need for diplomacy with Iran to de-escalate the growing nuclear crisis, since the current status quo is not sustainable. Absent limits on Iran’s nuclear advances, escalation to military action or sabotage to address the proliferation risk appears almost inevitable. The United States and Europe cannot afford to continue pointing the finger at Tehran for derailing JCPOA negotiations in August 2022 while waiting for the country to come back to the table.

US and European frustration with the current impasse and reluctance to reengage Iran is understandable. In late August 2022, the United States and Iran came close to reaching a deal to restore the JCPOA. Unreasonable demands from Iran over a separate IAEA investigation at the eleventh hour killed what EU foreign policy chief Josep Borrell called a “final” effort to revive the deal.

Since then, Iran’s brutal repression of protesters and its transfer of kamikaze drones to Russia for its illegal war in Ukraine have drawn US and European focus away from the JCPOA. Countering illegal drone sales and supporting protesters are laudable and necessary priorities, but the United States and Europe cannot lose sight of the growing proliferation threat and how current geopolitics may drive Tehran to decide nuclear weapons as necessary for its security.

There are three areas where the nuclear risk has increased over the past six months and will continue to grow (absent a deal or de-escalating steps from Iran): (1) expansion of enrichment at Fordow; (2) growth in Iran’s stockpiles of highly-enriched uranium; (3) and a growing monitoring gap. The urgency of this risk requires a new proactive diplomatic strategy.

Increased capacity at Fordow

In November 2022, Tehran announced its intentions to install an additional fourteen cascades of IR-6 centrifuges, which enrich uranium more efficiently, at its Fordow site and increase enrichment levels at the facility to 60 percent.

The Ebrahim Raisi government announced these plans after the IAEA’s Board of Governors censured Tehran for its continued failure to credibly respond to the agency’s questions about pre-2003 uranium activities, which were not declared to the agency as required by Iran’s legally binding safeguards agreement.

Prior to the November 2022 announcement, Iran operated two cascades of IR-6 centrifuges at the site and six cascades of less efficient IR-1 centrifuges. The machines produced uranium enriched to about 5 percent and 20 percent.

While the IAEA has confirmed that Iran is now enriching to 60 percent at Fordow, the February 28 report says it has not yet installed any of the planned IR-6 centrifuges. Regardless of the pace of expansion, however, undertaking these activities at Fordow is a significant escalation because of the location and nature of the facility.

Prior to the November 2022 announcement, Iran was only enriching to 60 percent at its aboveground facility at Natanz. Fordow, by contrast, is a hardened facility built in the mountains near Qom. Its small size and location suggest that it was originally built to produce material for a weapons program. More efficient centrifuges and a stockpile of 60 percent enriched uranium will enable Iran to quickly ratchet up its enrichment to produce weapons-grade material, possibly before the inspectors could detect a change and the United States could respond.

Under the JCPOA, Iran was required to halt all enrichment activity at the site for fifteen years. This is because the facility poses a greater risk than Natanz and would be challenging to destroy if the United States ever determined that military strikes were necessary to prevent Iran from developing nuclear weapons. Israel, for instance, would likely need US support to strike Fordow. Given these factors, higher levels of enrichment and increased enrichment capacity at Fordow are more proliferation sensitive than if the same activities were taking place at Natanz.

Growing stocks of highly enriched uranium

Iran is currently stockpiling uranium enriched to 60 percent and 20 percent levels. There is no civil justification for Iran producing uranium at these levels (as mentioned before, these stocks are about building leverage in negotiations with the United States and the risk they pose increases as the stocks grow).

Prior to the JCPOA, Iran enriched uranium to 20 percent. It resumed that activity in January 2021 as part of its response to reimposed US sanctions. It started enrichment to 60 percent for the first time in April 2021, following an act of sabotage at the Natanz enrichment facility. Sixty percent material can technically be used for a nuclear weapon, but the design would be bulky and inconsistent with the weapons-related design work Iran did prior to 2003. However, using 60 percent—or even 20 percent—enriched uranium as a starting point for enriching material to weapons-grade (90 percent) significantly reduces the time it would take to produce enough material for a bomb.

If Tehran started with 60 percent enriched uranium, for instance, it could produce enough 90 percent material for a bomb in less than a week—a timeframe referred to as “breakout.” This short window is quite worrying because Iran could try to achieve breakout between IAEA inspections, but it is not new. What is changing, however, is Iran’s breakout time to multiple weapons, which is largely due to the growing stockpiles of 60 and 20 percent material.

According to the February 28 IAEA report, Iran’s stockpile of 60 percent enriched uranium is 87 kilograms and its stockpile of 20 percent enriched uranium is about 435 kilograms. In late October 2022, the IAEA reported stockpiles of 62 kilograms and 386 kilograms, respectively. The 60 percent stockpile will likely grow more rapidly over this next year now that Iran is enriching to that level at both Natanz and Fordow.

With stockpiles of this size and a growing enrichment capacity, Iran could likely produce enough material for four weapons in less than a month. As that timeframe shrinks, which is likely given that Iran shows no signs of rolling back its enrichment, the proliferation threat will continue to increase.

This diminishing timeframe is significant because Iran is unlikely to breakout with just one weapon’s worth of 90 percent enriched uranium. One nuclear device is not a deterrent, particularly for a state like Iran that has never conducted a nuclear test. If Tehran can breakout to multiple nuclear weapons before the international community can detect and respond, the proliferation threat increases significantly. Enough material for multiple bombs also means that Tehran can divert the weapons-grade uranium to several covert sites, making it more difficult to detect and disrupt the weaponization process, which could take a year.

Monitoring gaps

While the IAEA still has regular access to facilities in Iran where nuclear materials are present, the agency’s blind spots are a growing concern that will continue to amplify over time. Since February 2021, when Iran suspended its more intrusive safeguards arrangement known as the additional protocol, inspectors have been unable to visit sites that support Iran’s nuclear program but do not contain nuclear materials. This includes facilities such as Iran’s centrifuge workshops, its uranium mines and mills, and its heavy water production facilities. Iran also disconnected cameras at some of these key locations in June 2022. The surveillance data was intended to allow the IAEA to reestablish a baseline for Iran’s nuclear activities if the JCPOA is restored.

For the first time, the IAEA said in its February 28 report that the monitoring gap will prevent it from reconstructing an accurate record of Iran’s nuclear activities in certain areas, such as centrifuge component production. As a result, the IAEA warned that baselines for verifying the JCPOA’s limits (if the deal is restored) “will take a considerable time to establish and would have a significant degree of uncertainty,” even if Iran cooperates with agency efforts. This finding has serious implications for the sustainability of a future deal, whether that be the JCPOA or a new agreement. If the IAEA cannot confidently verify limits, it will undermine confidence in Iran’s adherence to those restrictions.

The IAEA has continued to reiterate its concerns about the monitoring gap. IAEA Director General Rafael Mariano Grossi recently made this point in a February 7 discussion at Chatham House, when he said that “the gap” is worrying and that it will be “very difficult to restore a complete picture” of Iran’s nuclear program. He warned that the situation will “get worse” without dialogue.

No surveillance at these certain sites also increases the risk that Iran may divert materials, such as centrifuges, for a covert program. Iran may also try to take advantage of less frequent IAEA inspections at Natanz and Fordow to breakout or experiment with higher enrichment levels. A February 1 IAEA report, for instance, noted that Iran changed its IR-6 cascade configuration at Fordow without notifying the agency as required by its safeguards agreement. It was five days before inspectors returned to the site and detected the change.

Iran could try to exploit the gap between future inspections if the decision was made to breakout or divert materials. Less frequent inspections combined with the short breakout window also increases the risk that United States and/or Israel will miscalculate Iranian activities or intentions, increasing the risk of a military strike. Both the risk of undetected breakout and miscalculation were significantly less under the JCPOA, when inspectors had daily access to Natanz, where Iran could conduct limited enrichment, and Fordow, which was converted from a uranium enrichment facility to a research site.

A return to dialogue

The most effective way to address the growing proliferation risk posed by Iran’s rapidly advancing nuclear program would be to restore the JCPOA, which proved to be an effective and verifiable deal when it was fully implemented, but that path appears blocked for the near future, if not forever. Reviving the JCPOA, however, is not the only diplomatic option and, while US and European reluctance to reengage with Iran is understandable, it is not excusable. As Iran’s program advances, it will become more challenging to detect and disrupt a dash for the bomb.

In addition to the increased speed at which Iran could build several bombs, geopolitical factors could influence Tehran’s decision-making in favor of nuclear weapons. Currently, Tehran is paying a high cost for advancing its nuclear program without reaping any of the perceived security benefits of a deterrent. Sabotage or military strikes designed to set back Iran’s program—and the perception among certain leaders in Tehran that the West is supportive of regime change—could drive the Supreme Leader to the conclusion that nuclear weapons are necessary to defend the current governing structure and the territorial integrity of the state.

If the Joe Biden administration wants to prevent a nuclear-armed Iran or a war to stop it, Washington needs to act swiftly to reengage Tehran in negotiations—either as part of reviving the JCPOA or as a new diplomatic effort—that deescalate this crisis. It is past time that the United States and Europe returned to the negotiating table with a new strategy. A limited deal or a series of gestures that prevent further escalation could create the time and space necessary for new negotiations that guard against a nuclear-armed Iran in the long term.

Kelsey Davenport is the director for nonproliferation policy at the Arms Control Association.

Further reading

Tue, Dec 8, 2020

A history of continuity in Iran’s long nuclear program

IranSource By Sina Azodi

Iran’s interest in developing a nuclear deterrent is often attributed to the Islamic Republic. However, in reality, this interest predates the 1979 revolution and reflects a deep-seated desire for national prestige and development, as well as a need to deter regional rivals.

Thu, Jan 19, 2023

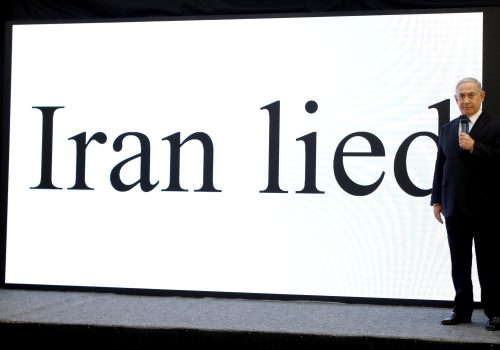

Netanyahu’s Iran policy is expected to fail—again

IranSource By Danny Citrinowicz

The biggest problem that Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu has today is the fact that he will have a tough time rallying the Joe Biden administration.

Fri, Apr 23, 2021

‘Poison pill sanctions’ are hard for Vienna negotiators to swallow

IranSource By Brian O’Toole

“Poison pill sanctions,” a large list of sanctions that would have been allowed under the 2015 nuclear accord, are clearly the sticking point in the ongoing negotiations and the focus of the technical working groups in Vienna.

Image: Head of Atomic Energy Organization of Iran Mohammad Eslami and International Atomic Energy Agency Director General Rafael Grossi attend the opening of the IAEA General Conference at their headquarters in Vienna, Austria, September 26, 2022. REUTERS/Leonhard Foeger/File Photo