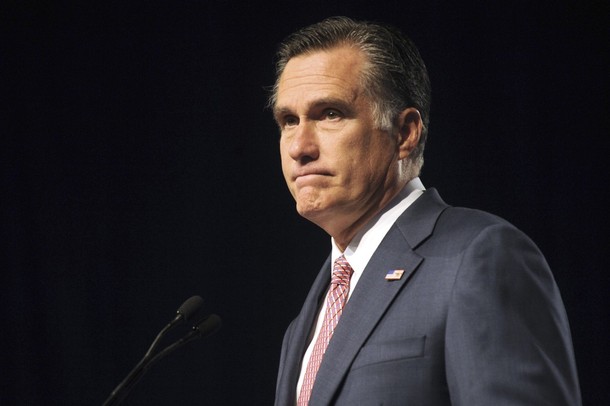

Mitt Romney’s first foreign tour as the Republican Party’s likely presidential candidate includes visits to two European states. While designed to send a message to potential voters at home, particularly blue-collar Reagan Democrats in the Midwest, the trip will be about photo opportunities. Romney’s visit to London is meant to echo his own successful management of the 2002 winter games in Salt Lake City and play into a campaign narrative built on executive experience and sober business acumen.

His visit to Gdansk and Warsaw will highlight the triangle that broke the back of communism: the Polish people’s courage, their Catholic faith and Western resolve. Not coincidentally, Polish-American immigrants dot the landscape in important battleground states such as Ohio and Pennsylvania.

Romney’s visit will inevitably draw parallels to that of candidate Barack Obama, who on a visit to Germany in July 2008, resolutely declared on the steps of Berlin’s Victory Column that he is a “citizen of the world.” Now the Republican candidate has an opportunity to articulate his vision for US relations with Europe, which has so far remained underdeveloped and reliant on dated platitudes.

Cold-War Rhetoric

At the moment, Romney’s European policy hints at a worldview more reminiscent of 1982 than 2012. In a March interview, Romney described Russia as the US’s “number-one geopolitical foe.” More recently, one of his top defense surrogates warned of the creeping Soviet threat in the Arctic. Another stated that the Obama administration’s decision to opt for a phased adaptive approach to missile defense was abandoning “Czechoslovakia.”

Individually these unfortunate statements are meaningless, but taken together they represent a worldview that is tinged with Cold War-era tropes. The Romney camp seems to overlook that Russia’s accordance of access to the International Security Assistance Force’s northern distribution network has been essential to the continuation of the mission in Afghanistan. His campaign also fails to remember that recent arms reductions in the new Strategic Arms Reduction Treaty make the US military more effective and the world safer, and that Russia’s entry this month into the World Trade Organization forces Moscow to accept higher standards for the rule of law.

That is not to say that US-Russia relations are unproblematic. Russia’s obstinacy in the face of the Syrian civil war runs counter to the humanitarian responsibility incumbent upon the United Nations Security Council’s permanent members. The Kremlin’s new, restrictive laws on non-governmental organizations and internet freedom also call into question even the most basic commitment to civil society. And the country’s endemic corruption is worrisome. Indeed, Russia’s relationships with the US and Europe are complex and wrought with difficulty. They cannot be boiled down into simplistic, anachronistic sound bites.

Lack of Vision

In Poland, Romney is expected to criticize the Obama administration’s reset policy with Russia. In fact, US and Polish approaches to Moscow have hewed closely together. Polish Foreign Minister Radek Sikorski has stated that his country started its own reset with Russia in 2007 and paved the way for the US to follow a similar path. Even in conservative Poland, Obama’s approval rating stands at 50 percent, up from George W. Bush’s 41 percent during his last year in office, according to the Pew Global Attitudes Survey.

Apart from criticizing Obama’s Russia policy, the most remarkable feature of Romney’s vision is his lack of approach. His 48-page document outlining his foreign-policy strategy does not once mention the North Atlantic Treaty Organization or the European Union. That will certainly be a source of concern for his European hosts, two of the largest members of both organizations and countries with two of the largest troop contingents to the NATO mission in Afghanistan.

The one bright spot in Romney’s trans-Atlantic vision has been his public call for a trans-Atlantic free trade agreement, a major positive agenda item that is sure to find support from Europe’s most important leaders including German Chancellor Angela Merkel.

But Romney has yet to address what role his administration would play in tackling the euro-zone crisis, now the most serious foreign-policy challenge for the US. Instead, Romney campaign rhetoric has used Europe as a foil in domestic-policy debates over debt and public spending: “We are increasingly becoming like Europe,” he has said. “Europe is not working in Europe. It will never work here.” He has stated that he would not allow America’s national balance sheet to be exposed to the euro-zone crisis, but the US is already exposed indirectly through trade, banking ties and returns on foreign direct investment. Romney will inevitably have to articulate a policy that recognizes America’s continued role as a European power.

Once upon a time, the Republican foreign policy brain trust was replete with some of the greatest minds on US relations with Europe. It was the creative tension in America’s center-right foreign-policy establishment from realists such as Henry Kissinger and Brett Scowcroft, to strident Cold Warriors such as Jeanne Kirkpatrick, to brash pragmatists such as James Baker that drove successful American foreign policy in the latter half of the Cold War, eventually leading to an unequivocal geopolitical triumph for the West. Today, however, the Republican candidate’s relations with Europe have been relegated to vague pronouncements. Romney’s trip to Europe gives him a chance to change that.

Annette Heuser is executive director, and Tyson Barker is director of trans-Atlantic relations at the Washington, DC-based Bertelsmann Foundation. Ms. Heuser is also an Atlantic Council board director. This article was previously posted in Der Spiegel.

Image: mitt%20romney.jpg