In mid-August, Israeli media Yedioth Ahronoth reported—citing anonymous Western intelligence sources—that China “is now actually rebuilding” Iran’s missile arsenal after the Twelve Day War between Iran, Israel, and the United States. The reporting provides no details and has not been confirmed by the Chinese government, but the anonymous allegations have since been repeated in Western newspapers. They have sparked considerable speculation about the reason why China would involve itself in a conflict it appeared so eager to avoid.

In reality, China’s involvement in Iran’s ballistic program is nothing new. It dates back to its beginning after the Iran-Iraq war in 1988, when the regime in Tehran prioritized missile production. After suffering years of Iraq’s Scud attacks on Iranian cities, missiles were to become a central component of Tehran’s military strategy. To that effect, the country relied on external partners, namely North Korea and China, to access technology and train its engineers. China eventually supplied Iran with short-range ballistic missiles as well as cruise and anti-ship missiles. To be clear, Beijing not only contributed to Iran’s ballistic program during this time, but it also sold DF-3 intermediate-range ballistic missiles to Saudi Arabia in 1988.

However, Iran quickly aimed to build its domestic defense industry for missile development and production. As a result, China’s footprint remained relatively small. Beijing focused less on selling “off-the-shelf” systems than on providing the Iranian military-industrial complex with scientific expertise and specific components. Specifically, China helped Iranian engineers make progress regarding the propulsion and guidance systems of their arsenal. Military analysts estimate that Iranian ballistic missiles like the Shahab-3 or the Fatah-110 relied on Chinese components. In fact, some of the missiles transferred by Iran to Hezbollah in Lebanon and the Houthis in Yemen were believed to be copies of Chinese C-704 and C-802 missiles. In exchange for this technical assistance, China received Iranian oil supplies at a discount price.

For Western intelligence agencies, the nature of that cooperation makes it much harder to detect than the mere export of completed weapons. The transfer of knowledge or dual technologies also attracts less attention, making it much more difficult to raise public awareness on these exchanges. US administrations, starting under former President Bill Clinton’s presidency in the 1990s, condemned Beijing’s support of Iran’s ballistic program, but it never became a major issue on Washington’s agenda.

One could counter that these developments are three decades old. They relate to a period, the early 1990s, when China was not yet the global power it is today. The 1989 Tiananmen Square massacre had tarnished Beijing’s international image, and its engagement with the international community was more limited. China, for example, has not signed the Missile Technology Control Regime (and still hasn’t), and it joined the Non-Proliferation Treaty only in 1992.

Still, it is worth noting that this China-Iran missile cooperation never completely stopped. In fact, in late April 2025—barely a month before Israel launched its air campaign on Iran—the US Department of Treasury listed six Chinese entities and six individuals responsible for providing the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC) with “propellant ingredients” used to produce the solid-fuel needed for the propulsion of Iran’s missiles. Again, because of the technical nature of those exchanges, the statement received limited coverage in the public space.

Against that backdrop, the latest reports from Israeli Media do not reveal a turning point in China’s engagement with Iran, but their timing still matters for several reasons. First, it highlights the critical need for Iran to rebuild its arsenal after the Twelve-Day War. Prior to Hamas’ October 7, 2023 assault on Israel and the regional conflict that followed, Iran’s military strategy relied on its ballistic missiles and its constellation of proxies across the Middle East, (including Hezbollah, Houthis, the Palestinian Islamic Jihad, among others), as a means of deterrence against Israel. Today, Israel’s recent military operations have largely weakened those non-state partners, and they are no longer able to provide Tehran with the strategic depth it once enjoyed. As a result, the most effective way for the IRGC to restore a credible deterrence against Israel goes through rebuilding its missile inventory.

Given the damage caused by the Israeli airstrikes on missile storage units and factories, Tehran’s rearmament process will be long and expensive. Independent experts suggest that it could take at least a year to reach the level prior to June’s Twelve-Day War. To do so, Iran needs external support. Russia is the most obvious choice. Moscow has long supplied Iran’s air defense systems, and military cooperation between Moscow and Tehran intensified in the past two years, as Iran provided unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs) and drones to shore up the Russian military campaign in Ukraine. However, the prolonged conflict with Kiev has drained most of Russia’s resources, and its defense industry cannot deliver what Iran needs. The Chinese military-industrial complex is therefore in a better position to meet the needs of the IRGC.

Beyond gauging the extent of the current cooperation between Beijing and Tehran, the timing also matters because it comes at a time of much speculation regarding a new war between Israel and Iran. The disclosure of Israeli intelligence assessments conveys the message to Beijing that in the post-October 7 environment, Israel no longer tolerates such activities and may act upon them. It is meant to convince China to stay away from the Iranian rearmament process.

On its own, Israel cannot coerce China, and the US administration is unlikely to make Beijing’s missile cooperation with Iran its top priority. However, there are ways Washington could put greater pressure on China to stay away from the Iranian ballistic enterprise. In the context of the ongoing trade negotiations between Beijing and Washington, the suspension of China-Iran military cooperation could be a condition for Chinese companies to gain access to US technologies, such as Nvidia’s microchips.

If such demands are not met, the United States could also increase the publicization of these Chinese actions toward Middle East partners, such as the Gulf states. Such publicization acts as an inconvenient reminder of China’s military activities in the region. Under the reign of Xi Jinping, PRC officials have constantly affirmed that they have no interest in getting embroiled in local conflicts and that they do not supply weapons to warring parties. Instead, the Chinese government favors relations driven by mutually beneficial trade deals. Beijing’s 2016 Arab Policy Paper talked of “win-win results” and condemned “external interference.”

The history of China’s involvement in missile programs in the Persian Gulf undermines this positive narrative and stresses the contradictions of China’s missile policy in the region. Chinese entities are reportedly supporting Saudi local production of missiles. Meanwhile, Qatar displayed a Chinese short-range ballistic missile during its national day military parade in 2017. These transfers can have dramatic consequences: In 2016, a vessel from the United Arab Emirates Navy was struck by a Houthi missile that Iran provided, and that very likely was a copy of a Chinese one.

China’s indiscriminate policy of missile transfers feeds the regional arms race and ultimately impacts the national security interests of US allies like Israel and the Gulf states. With a new war between Iran and Israel still a real and immediate threat, China might need to ask itself: Is it worth maintaining military cooperation with Iran at the expense of its self-declared “win-win” diplomacy in the Persian Gulf region?

Jean-Loup Samaan is a nonresident senior fellow at the Atlantic Council and a senior research fellow at the Middle East Institute of the National University of Singapore.

Further reading

Tue, Aug 5, 2025

Did the Israel-Iran war expose China’s Middle East policy?

MENASource By

The region’s importance in Beijing’s foreign policy is limited and, thus, not much energy and resources are invested in long-term planning.

Wed, Jul 23, 2025

Iran, China, Russia, and the collapse of deterrence in the Red Sea

MENASource By

Multiple powers now patrol with different mandates, different rules, and increasingly different interpretations of acceptable behavior.

Thu, Jul 31, 2025

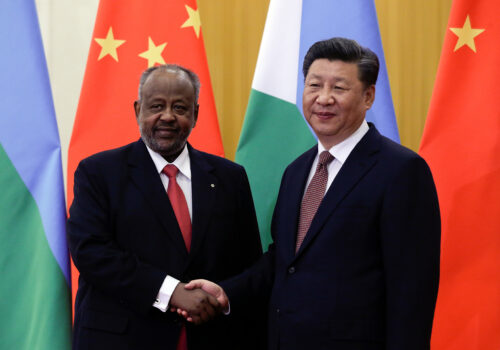

Djibouti is the next arena for US-China competition in the Red Sea

MENASource By Emily Milliken

Washington could upgrade its Djibouti relationship and secure its foothold along some of the world’s most important waterways.

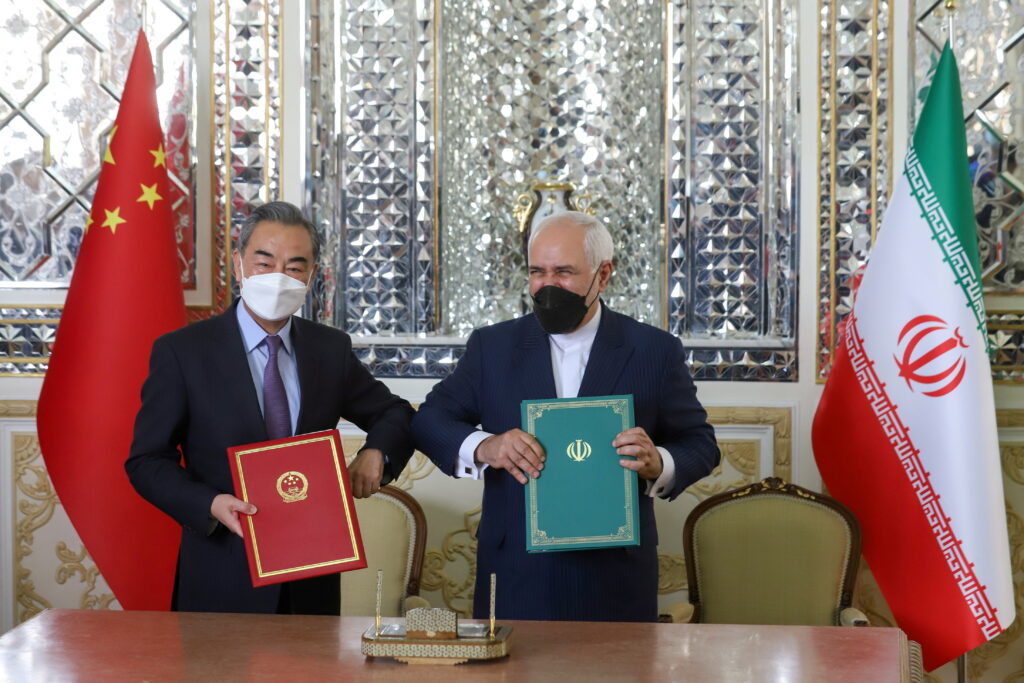

Image: Iran's Foreign Minister Mohammad Javad Zarif and China's Foreign Minister Wang Yi bump elbows during the signing ceremony of a 25-year cooperation agreement, in Tehran, Iran March 27, 2021. Majid Asgaripour/WANA (West Asia News Agency) via REUTERS ATTENTION EDITORS - THIS IMAGE HAS BEEN SUPPLIED BY A THIRD PARTY.