In September, the radical jihadist group ISIS launched a major offensive in northeastern Syria, overrunning scores of Kurdish villages along the warpath to Kobani, a strategic town on the Turkish border. The bloody campaign created the largest refugee surge of the war—forcing 200,000 Syrians across the border in two weeks—and again brought to the fore the Turkish proposal for a humanitarian buffer zone.

In September, the radical jihadist group ISIS launched a major offensive in northeastern Syria, overrunning scores of Kurdish villages along the warpath to Kobani, a strategic town on the Turkish border. The bloody campaign created the largest refugee surge of the war—forcing 200,000 Syrians across the border in two weeks—and again brought to the fore the Turkish proposal for a humanitarian buffer zone.

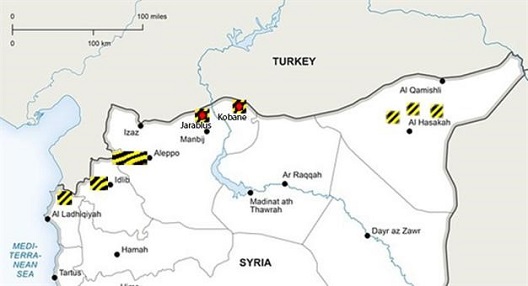

Since 2012, the government of Turkey has advocated for the creation of an internationally sanctioned buffer zone—sometimes called a safe zone—a militarized ribbon running the length of the Turkish/Syrian border, protecting a dozen or so Syrian population centers.

The argument for a buffer zone is demonstrated most clearly in Kobani, where evacuated residents camp on Turkish hilltops overlooking their abandoned homes. If the Turkish military could push several miles into Syrian territory, the thinking goes, then Kobanis could stay put in their homes (and go to school, and tend to their shops, and till their fields) rather than huddle in UNHCR tents. And Turkey, which already hosts upwards of one million registered refugees, could relieve itself of the complex burden of hosting displaced Syrians.

Earlier this month, Prime Minister Ahmet Davutoğlu publicly laid out the Turkish vision for “a humanitarian safe zone under military protection” inside Syria. Areas designated for protection would be population centers “over a certain density” and the passages necessary to reach them.

On its face, the idea has a certain appeal, but there are concerns as well. (Beyond humanitarian concerns, the buffer zone likely has politico-military functions: the cleared zone could be used as an area to train forces opposed to Assad, and the incursion would create the pretense for the Turkish military to destroy PKK installations.)

To help us better understand this issue and the ramifications for refugees and refugee policy, we posed several questions to a leading expert on population displacement, Elizabeth Ferris, Senior Fellow at the Brookings Institution:

1. Is the Turkish buffer zone an unusual proposal? Is there precedent for a neighboring country establishing a protectorate within the conflict country?

Probably the most relevant precedent is Northern Iraq in 1991 when Turkey was faced with the possibility of a mass influx of Iraqi Kurds fleeing violence after their attempted uprising against the Saddam Hussein regime. Turkey responded by closing the border and taking the issue to the UN Security Council which defined the situation as a threat to international peace and security. While the UN did not authorize a “safe zone,” the US and ten other countries deployed 20,000 troops in Operation Provide Comfort to protect and support some 450,000 or so displaced Iraqis. Most of the internally displaced persons (IDPs) returned to their communities after a month or so.

While as in 1991, Turkey wants to halt the influx of hundreds of thousands of Kurdish refugees, today’s situation is different in several important respects. A buffer zone or safe zone depends on military protection—I don’t sense any outpouring of support for enforcing a no-fly zone or putting troops in the area to ensure that displaced Syrians are safe. Indeed I worry about some of the comments that a buffer zone would not only protect Syrian civilians but also provide an area for the Syrian opposition to organize a military response. Any time you mix military operations with protecting civilians, the civilians are put at risk. The Syrian regime could bomb the buffer zone on grounds that it is a military target. Are Turkey and its allies ready to engage in full-scale war with the Syrian government if Syria does violate a buffer zone? And even if such a buffer zone were established, what’s the end game? Would Syrians stay there for a month or two and then return safely to their homes? I just don’t see Syrians being able to return quickly. The worst of all worlds would be to encourage Syrian civilians to move to a buffer zone for their own safety and then fail to protect them—opening up the possibility that they would be at even greater risk as sitting ducks.

Discussions around a buffer zone seem to have mixed motivations—to protect civilians, to keep refugees out, to support opposition groups. But if the intention is to keep people safe, then the answer is for them to be allowed to enter Turkey where they can be protected and assisted. I understand that Turkey (and other countries) are reluctant to open their borders to large numbers of refugees—international support has not been able to compensate for the very real costs incurred by the presence of over three million refugees in the region. But in terms of keeping people safe, Syrian refugees in Turkey are much safer than Syrian IDPs on the Syrian side of the border with or without a buffer zone.

2. At the moment the Turkish buffer zone exists only as a plan, so any concerns are hypothetical, but it seems that there could be a big difference in the emphasis of implementation—for example, there would be a big difference between protecting vulnerable populations still inside Syria versus setting up a safe zone in order to compel refugees to return. What are Turkey’s relevant obligations under international refugee convention? Would Turkey’s obligation to protect refugees disappear once they are on Syrian soil?

Turkey is a signatory to the 1951 Refugee Convention but maintains the geographic restriction limiting refugee status to Europeans. But when Syrian refugees began to arrive in 2011, the Turkish government not only kept the border open, but offered them a form of temporary protection and established camps with a full range of services. Today there are over a million Syrian refugees in Turkey, most now living outside of camps.

Central to international refugee law is the provision against non-refoulement, that is not sending people back to situations where their lives are in danger. I don’t think anyone seriously thinks that returning Syrians from Turkey back to Syria is safe. Even if they’re returned to a buffer zone, this is a violation of the spirit—if not the letter—of international refugee law. Turkey is also a signatory to the UN Convention against Torture which includes an international obligation not to return people to situations where they are at risk of torture. Given the reports of ISIS atrocities, it would seem to be a clear violation of Turkey’s obligations not to return Syrians to a situation where they are at risk of torture.

3. Are you concerned about the precedent this would set, in this conflict and in others? Are you concerned that other host countries might view the safe zone model as a convenient way to push unwanted refugees back across the borer—essentially converting refugees into IDPs? Even if Turkey provided exemplary service in this instance, the safe zone model is corruptible—we can imagine a host country parking an army jeep just across the border and declaring it a safe zone.

Governments in the region—particularly Lebanon, Jordan and Turkey—are reeling from the impact of refugees. Turkey isn’t the only country which would like to have some justification for closing their borders or restricting entry by setting up programs for displaced Syrians inside Syria. And Turkey has far more resources than other host countries. If Turkey, with its 80 million people, says it can’t deal with the influx of Syrian refugees, why should Lebanon (population four million) or Jordan do more?

Frankly, this is a terrible situation. The host countries, including Turkey, need more international support to provide basic services to Syrian refugees. But the international community has responded generously to the Syrian refugee crisis—at a time when the whole humanitarian system is under strain from multiple major crises (Ukraine, South Sudan, Central African Republic, Ebola). I just don’t see how the necessary funding can be mobilized to ease the burden on the countries hosting Syrian refugees—and hosting them with no end in sight.

This situation also highlights the particular challenges of working with IDPs inside Syria. While we hear a lot about the three million Syrian refugees, there are at least twice that number who are displaced within the country. Much less is known about their conditions and about the aid they’re receiving. They are likely to be more vulnerable than refugees because they’re closer to the violence and assistance is even more limited. The international system does much better at responding to human need when it is in the headlines of newspapers. IDPs are largely out of sight and out of mind.

4. The United Nations has said publicly that it would deliver aid within a buffer zone, even if the zone is established without a Security Council resolution. What administrative challenges could you foresee inside the buffer zone? Would relief agencies answer to Damascus? To the local councils? To Ankara? To Turkish generals?

Presently, the situation of cross-border humanitarian operations inside Syria is murky territory. A number of groups, including Turkish groups supported by the Turkish government, are providing needed assistance which is keeping people alive. But there are questions about some of the groups who are delivering aid, about the motivation of the assistance, and about where the aid is actually ending up. Presently (and to oversimplify), relief agencies have to choose between working in regime-controlled areas (and thus getting permission from Damascus for their programs) or working in other areas where coordination is sorely lacking. There are some wonderful Syrian organizations providing aid outside of areas under regime control, but they’re working under dangerous conditions and their relations with UN agencies are tenuous. I’m hard-pressed to see how they would work more effectively in a buffer zone. Actually, unless there’s clear military control and oversight of a buffer zone, it’s hard to see who would be “in charge” of aid inside such a zone. And if there is strong military control of such a zone, there would be resistance by humanitarian groups to have their aid subject to military control.

5. Looking to the future, some observers fear that if Aleppo falls to the regime or ISIS, another one to three million refugees could flee north. In this terrible situation, do you think the buffer zone would be helpful?

Obviously the pressures of another million-plus refugees from Aleppo arriving on the Turkish border are worrying. But without a lot more thought about a buffer zone, I don’t think such a zone is the answer.

This has been a pretty depressing interview, Matt, and I don’t want to end on a note of despair. Beyond the political issues, don’t underestimate the impressive hospitality of the Turkish people. Even though the hospitality is wearing thin and there are signs of a backlash, Turks have been incredibly generous. They know about the violence and the terror inside Syria. I think if there is a major offensive and people have to flee, there will be important Turkish voices urging a compassionate response.

Elizabeth Ferris is a Senior Fellow at the Brookings Institution. Follow her on Twitter @Beth_Ferris. Matthew Hall, assistant director at the Atlantic Council’s Rafik Hariri Center for the Middle East, conducted the interview. Follow him on Twitter @WoodworthHall.

Image: Kurdish civilians on a Turkish hilltop watch fighting across the border in Kobani, Syria, under siege by ISIS militants. (Photo: REUTERS/Umit Bektas)