Even as, coming out of the annual NATO summit in Wales, the United States and its allies are promising to ratchet up their response to the Islamic State in Iraq and Syria, another militant group, Boko Haram, is rapidly gaining ground in Africa, achieving many of the same operational and strategic successes that have made ISIS such a force to be reckoned with, including significant dominion over territory and populations.

More alarmingly, except for a fleeting moment earlier this year when the brutal kidnapping of nearly three hundred schoolgirls and the ensuing social-media campaign focused the spotlight on the Nigerian marauders, the burgeoning threat is receiving little of the attention it deserves and even less of the resources necessary to combat it.

Several years ago, in a National Defense University-published study, I warned that the formerly obscure group had not only survived a ham-fisted attempt to suppress it, but was actually expanding both its reach and the scope of its operations, thanks in part to assistance from foreign terrorist organizations, including some linked with al-Qaeda. As a result of these links, against the conventional view at the time, I saw a significant shift in Boko Haram’s message and its capabilities, forecasting that, if left unchecked, it would metastasize into a much more lethal threat, both to Nigeria and its neighbors and to the wider international community.

Three months ago, in testimony before the US Congress, I surveyed the extent to which that threat had actually evolved over time, arguing that if the foreign links were a critical part of Boko Haram’s ideological and operational shift from “version 1.0” to the far more lethal “version 2.0,” the takeover of northern Mali by various Islamist militant groups aligned with al-Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb (AQIM) in 2012 provided a whole new set of opportunities, leading to what I have termed “version 3.0.” Specifically, I noted that, during the time AQIM and its allies held sway over northern Mali, Boko Haram was able to set up a number of bases in the territory where hundreds of its recruits received ideological instruction, weapons and other training that subsequently raised the tactical sophistication and operational tempo of its attacks in Nigeria, elevating the group to the level of a full-fledged insurgency.

Following the French-led intervention in Mali in early 2013, the Nigerian militants, possibly accompanied by a few foreign nationals, returned to northern Nigeria not only with training and some combat experience in desert warfare, but also vehicles and heavy weapons, including shoulder-fired missiles. Within weeks, Boko Haram fighters were raiding military barracks for even more weapons, staging increasingly bold prison breaks, destroying numerous schools, hospitals, and other government buildings, engaging the Nigerian military in pitched open battles, and, in some cases, totally overrunning border towns. By the middle of 2013, the militants had effectively evicted Nigerian government troops and officials from at least ten local government areas in northeastern Borno State along the borders of Niger, Chad, and Cameroon and set themselves up as the de facto authority in the region, replacing Nigerian flags with their own banner, taxing and otherwise ordering citizens about, and creating a large area, roughly the size of the state of Maryland, within which they could operate with even greater impunity, including launching the infamous raid in April that resulted in the kidnapping of the schoolgirls from Chibok.

Thus “Version 3.0” of Boko Haram is distinguished from previous phases by the group’s ability to seize and hold territory—much like what al-Shabaab has done for years in Somalia, AQIM did in Mali in 2012, and ISIS is doing in Iraq and Syria today—and the militants have been doing so at an alarming rate. Up until recently, the area controlled by Boko Haram was remote and sparsely populated, but that has been changing.

On August 6, fighters from Boko Haram captured the town of Gwoza, on Nigeria’s border with Cameroon. On August 25, after having destroyed a month earlier the bridge on the road linking the town to the Borno State capital of Maiduguri some 120 kilometers to the southwest, the group attacked and destroyed army barracks in the town of Ngala, just south of Lake Chad, and then proceeded to take the town of Gamboru, a few kilometers away. The seizure of the twin towns gave Boko Haram control of a local government area with a population of roughly a quarter of a million people. A week later, on September 1, Boko Haram fighters swung clockwise to overrun their biggest prize yet, Bama, a city with a population of nearly 300,000 just 60 km southeast of Maiduguri.

While, at least for the moment, it seems unlikely that Boko Haram has the wherewithal to try to seize Maiduguri, an urban sprawl with more than a million inhabitants plus countless others who have fled there as outlying areas fell to the militants, territory they now hold does form a pincer around the city and, undoubtedly, they will launch probing attacks that will add to the misery of those now caught inside. Meanwhile, Boko Haram has gone on the offensive beyond long-suffering Borno State to take over towns and local government areas in neighboring states. Following an assault that began at the end of July, Boko Haram gained control of Buni Yadi, the headquarters of the Gubja local government area in Yobe State to the west of Borno, on August 21. On September 6, the government of Adamawa State to the south of Borno confirmed that the insurgents had entered the town of Gulak and overrun the surrounding Madagali local government area; Reuters correspondents spoke with witnesses who told of militants going house to house shooting people. The following day, after a failed military attempt to retake the captured area, thousands of panicked residents from nearby towns were reported to have fled their homes and begun trickling into the state capital of Yola. On September 8, Abuja’s Leadership newspaper reported that Boko Haram forces had chased the military from Michika, the headquarters of the most populous local government area in Adamawa, and foisted the group’s black flag over the town.

Meanwhile, over the weekend, a Nigerian defense official announced airstrikes against the insurgents occupying their recent conquests, but it is not immediately clear whether the sorties had the intended effect, much less their impact on the unfortunate civilian population caught in the targeted towns.

Where it has taken control, Boko Haram, like its ISIS counterpart in the Levant, has raised its black flag over public buildings and brutalized those who failed to adhere to its extremist Islamist strictures. In Yobe State, according to AFP reports cited by Al Jazeera, two people caught smoking cigarettes were summarily executed late last month. In Borno State, the spokesman for the Roman Catholic Diocese of Maiduguri, Father Gideon Obasogie, told journalists last weekend that the insurgents were beheading men who refused to convert to Islam and forcing their widows to convert and marry militants. According to a tally by Open Doors, a Netherlands-based non-denominational international organization that advocates for Christian victims of religious persecution, more than 178 churches had been destroyed by Boko Haram as of the end of August. Muslims who do not share Boko Haram’s extremist ideology have also been targeted: Gamboru Ngala residents recounted that the Islamists executed the area’s most senior Muslim cleric after overrunning the district last week, while at the end of May the Emir of Gwoza, Shehu Mustapha Idrissa Timta, was killed by Boko Haram a few weeks after he gave a speech denouncing the group’s violence (two other traditional rulers, Abdullahi Ibn Muhammadu Askirama, Emir of Askira, and Ali Ibn Ismaila Mamza II, Emir of Uba, barely escaped the ambush).

And it is not just Nigerians who are suffering from the predations of the militants. In late May, Boko Haram fighters ambushed a Nigerien patrol in the region of Diffa, north of Borno. At the end of July, the wife of Cameroon’s Deputy Prime Minister Amadou Ali and a local traditional chief were kidnapped by the group from Kolafata, in the far northern part of the country.

Despite the largest defense budget in Africa, commensurate with their position as the most populous country and largest economy on the continent, Nigerians have very little to show for it. It is bad enough that none of the Israeli-made Aerostar drones Nigeria purchased a few years ago, reportedly for almost a quarter of a billion dollars, had been maintained and were inoperative when needed in the search for the kidnapped girls this spring, but the country’s security forces are so ineffective that Boko Haram has managed to steal their vehicles literally from underneath Nigerian soldiers: according to eyewitness accounts reported in the Nigerian press, during last week’s assault on Bama, the militants deployed over a dozen armored vehicles they had taken from the military when they captured Gwoza last month. And the troops that are supposed to oppose the militants are so demoralized that, more often than not, they flee without putting up much, if any, fight. Despite efforts by Nigerian defense officials in the federal capital of Abuja to try to explain the presence of a full battalion of their soldiers in neighboring Cameroon as a “tactical maneuver,” it is hard to credit that spin when the unarmed unit was returned en masse by the Cameroonians at the border town of Mubi, Adamawa State, miles south of the fighting in Borno. The Nigerian press reported that the members of the battalion claimed to have joined civilians in flight after running out of ammunition. Late last week, according to a Voice of America report, Cameroonian officials took in another 400 Nigerian soldiers who handed over their weapons at the border town of Amchide and sought refuge from the fighting.

One has more sympathy with the nearly 10,000 Nigerian refugees whom the United Nations says have fled for sanctuary in Cameroon over the last two weeks as well as the more than 2,000 who have taken refuge in Niger, joining the 50,000 who have fled to that poor country since last year.

Perhaps even more troubling than the humanitarian challenge posed by the refugees as well as the hundreds of thousands of internally-displaced persons is the growing ambitions of Boko Haram’s emir, Abubakar Shekau, who proclaimed a “caliphate” in northern Nigeria in an hour-long video released on August 24: “Thanks be to Allah who gave victory to our brethren in Gwoza and made it part of the Islamic caliphate… We did not do it on our own. Allah used us to captured Gwoza; Allah is going to use Islam to rule Gwoza, Nigeria and the whole world. ” In reporting the rambling message, Al-Jazeera noted that while the Boko Haram chief had previously voiced support for ISIS leader Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi, there was no indication in the new video that the former was still associating himself with the latter and “as such, it was not clear if Shekau was declaring himself to be a part of Baghdadi’s call or if he was referring to a separate Nigerian caliphate.”

Speaking in Nigeria last week at the opening of the US-Nigeria Binational Commission’s Regional Security Working Group, Assistant Secretary of State for African Affairs Linda Thomas-Greenfield was characteristically straightforward about recent developments: “Boko Haram has shown that it can operate not only in the northeast but elsewhere in the country. We are very troubled by the apparent capture of Bama and the prospects for an attack on and in Maiduguri which would impose a tremendous toll on the civilian population. This is a sober reality check for all of us. We are past time for denial and pride.” She announced that, as part of the Security Governance Initiative announced by President Barack Obama during last month’s US-Africa Leaders Summit to facilitate comprehensive security sector governance and accountability mechanisms, the United States was planning to launch a “major” border security program for Nigeria and its neighbors.

While this is a very welcome start, the United States, its African partners, and the rest of the international community will need to focus more attention and resources—and, as I have repeatedly stressed, the effort will require political, economic, and social instruments, not just military ones—on a situation that is already pretty dire, but could deteriorate significantly very rapidly. Otherwise, ISIS won’t be the only Islamic State against which a strategy will have to be developed and a coalition assembled.

J. Peter Pham is director of the Atlantic Council’s Africa Center.

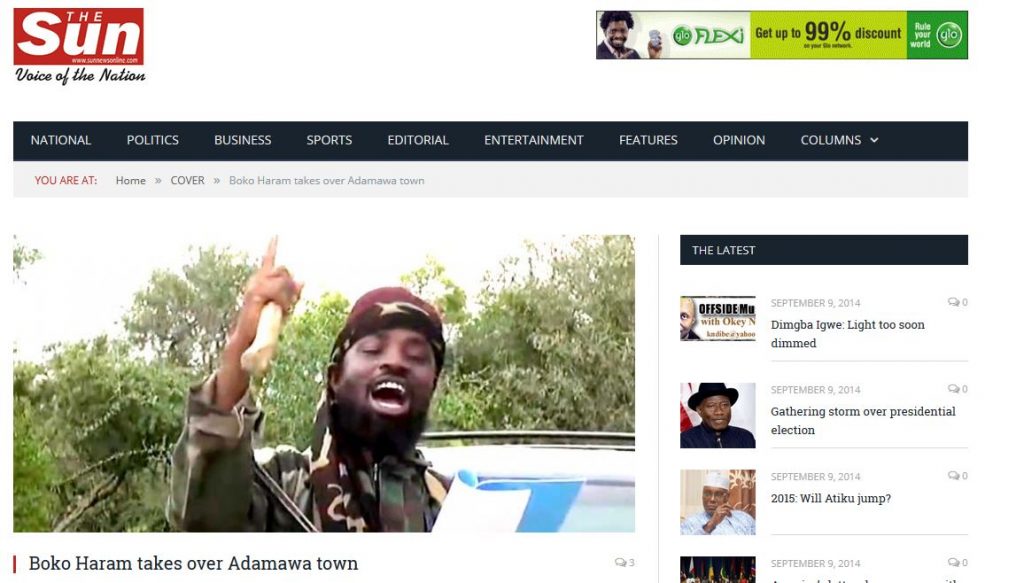

Image: A headline in The Sun, a Nigerian tabloid daily, reports a military advance by Boko Haram last weekend under a video image of the group's leader, Abubakar Shekau. (The Sun/www.sunnewsonline.com)