Amid surging public outrage in Nigeria and abroad over Boko Haram’s kidnapping of 223 schoolgirls, President Barack Obama has promised that the United States will do “everything it can” to rescue them. His promise follows a pledge by Secretary of State John Kerry to do “everything possible” to help the Nigerian government defeat Boko Haram, a Muslim rebel group that has terrorized the impoverished northern regions of the country.

The White House yesterday announced a plan to send an interdisciplinary team of US military and law enforcement personnel skilled in intelligence gathering, hostage negotiation and victims’ assistance to Nigeria. While this team no doubt will be capable of offering invaluable expertise to the Nigerian government, a statement by White House spokesperson Jen Psaki indicated that it will be based at the US Embassy in Nigeria’s capital, Abuja.

Therein lies a problem, for Abuja is 350 miles from the border of Borno State, where the kidnappings took place, and 500 miles from Maiduguri, the Borno state capital and epicenter of the Boko Haram crisis.

The ability of US specialists to help in the hunt for the missing girls obviously will be less effective if they are forced to operate from Abuja. But a law called the Leahy Amendment strictly prevents US government agencies from providing direct assistance to any foreign military unit that is suspected of violating human rights. Before the American “coordination cell” can set foot in northern Nigeria, they somehow will have to certify that the Nigerian troops they’re there to help aren’t guilty of perpetrating human rights abuses.

That’s likely to be impossible. The Nigerian military has been widely accused—by local witnesses, Amnesty International and other human rights groups–of killing thousands of people in its efforts to destroy Boko Haram since 2010—many of them innocent civilians. The military is accused of burning an entire village to the ground in April 2013 and of summarily executing scores of suspects. Because the murder of civilians is believed to be so extensive and systemic, finding a Nigerian military unit that doesn’t have blood on its hands will be difficult – and it may require shipping an entirely new crop of Nigerian soldiers up to the north. (If indeed, units with “clean hands” can be found at all; large numbers of Nigerian soldiers already have been rotated in and out of the counterinsurgency campaign.)

If the Leahy Amendment becomes an impediment to finding the missing girls, it may come in for criticism. It shouldn’t; the legislation was created for good reason, to prevent the US military from being implicated in the human rights abuses of foreign governments. Almost exactly a year ago, those abuses by Nigerian troops forced Kerry to declare that “we are … deeply concerned by credible allegations that Nigerian security forces are committing gross human rights violations, which, in turn, only escalate the violence and fuel extremism.”

For years, Washington has invested its resources in strengthening the Nigerian military. The national security interests involved in that decision had little if anything to do with the threat Islamic militancy from Boko Haram or other radical groups—it was to help assure the stability of Africa’s largest oil producer. During 2008 to 2013, the United States imported an average of 726,000 barrels of oil daily from Nigeria, just over 6 percent of its total imports.

While Boko Haram is an appropriate target for US counterterror efforts, Washington should be wary indeed of putting an American face on the brutally oppressive tactics of the Nigerian military. That would simply play into the hands of true radicals who want to do the United States harm.

These legal and political complications make it unlikely that U.S. assistance to Nigeria will be instrumental in finding the missing children. Time to help them is fast running out, if it isn’t already too late: the State Department has expressed its fear that many of the girls have already been sold into slavery in the neighboring countries of Cameroon and Chad.

That doesn’t mean that Washington’s efforts are futile: there will surely more victims in the future (Boko Haram attacks on the villages of Gamboru Ngala and Warabe have been reported in the past two days), and if the United States can help the Nigerian government to reign in the excesses of its soldiers, local citizens might be more willing to share vital information with investigators and troops. But that is an effort that will take months or years, not days, to bear fruit.

Bronwyn Bruton is deputy director of the Africa Center at the Atlantic Council.

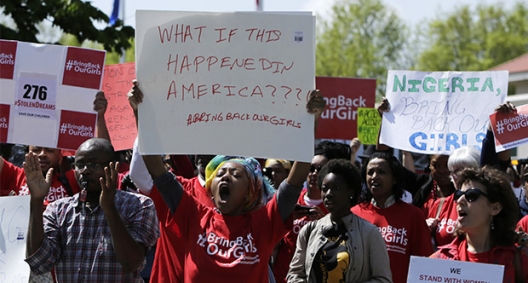

Image: Protesters march in support of the girls kidnapped by members of Boko Haram in front of the Nigerian Embassy in Washington May 6, 2014. REUTERS/Gary Cameron