In July, France’s parliament ratified a new law to tax big digital tech firms making it the first country to pass a tax law of this manner. Paris’ new tax scheme triggered criticism from the Trump Administration and is further complicating the transatlantic relationship. This edition of the EconoGraphic explains the motivation behind taxing digital technology firms more aggressively, the way that the French tax will work, and the potential impacts and response to the tax.

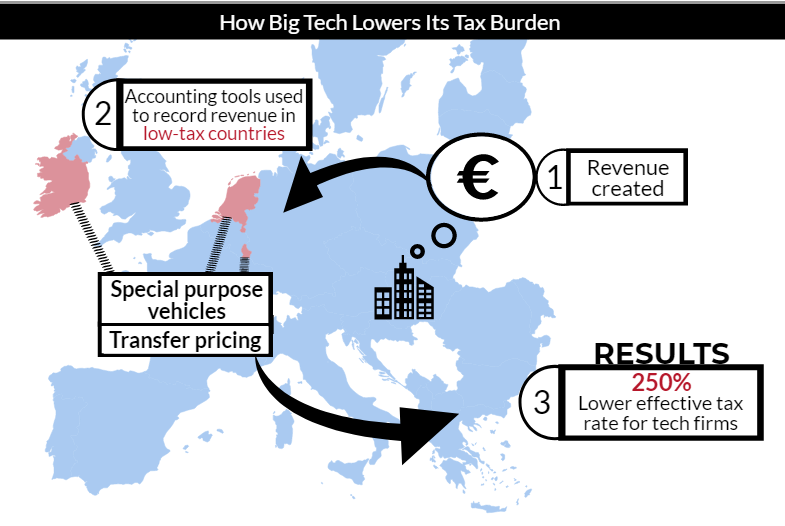

Taxing tech giants is not a new idea. As a result of French pressure, the EC initiated a discussion about an EU wide digital tax. However, EU member states could not agree on a common approach toward large tech companies. To understand why the French government has decided to tax big tech, it is important to understand the current tax structures in the EU. Each EU member state sets their own corporate tax rate, with some much lower than others. The big four (Google, Amazon, Facebook, and Apple) have users across the EU, and through targeted advertising and purchases on the platforms, they collect revenue in both high-tax and low-tax countries. These big companies employ two legal methods to avoid paying taxes in the high-tax countries. Using transfer pricing, firms can essentially move their money earned in one jurisdiction to low-tax jurisdictions, allowing them to pay much lower tax rates on revenue earned around the continent. Firms also establish special purpose vehicles(SPVs) in low-tax jurisdictions, allowing them to effectively shield revenue earned, and thereby not pay any taxes on it. In turn, big tech firms pay an average effective tax rate of only 9.5% on generated revenue, whereas the average EU business pays an average effective tax rate of 23.5%

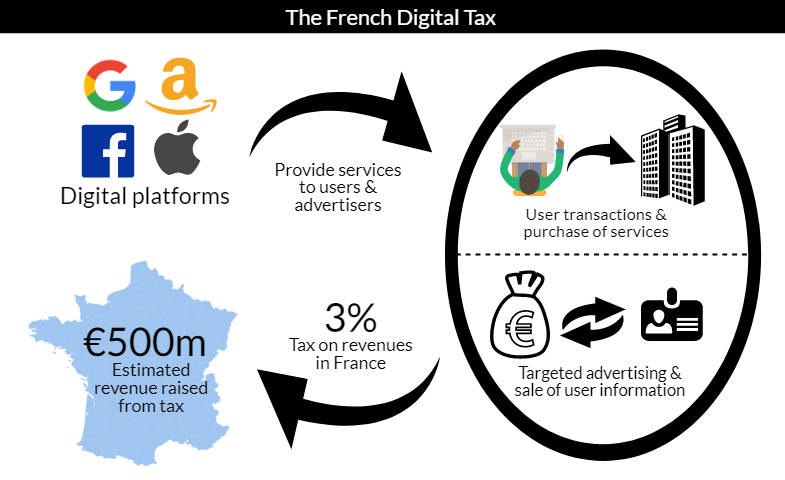

Citing the disparity in effective tax burden, France’s new tax will target firms that earn over €750 million worldwide and at least €25 million in France. Macron’s ministry of Economy and Finance predicts that around 30 firms will be subject to the new tax, most notably Google, Amazon, Facebook, and Apple. The tax will apply to different types of digital interactions. For digital interfaces, it will tax transactions concluded while one of the users is in France, such as a purchase on Amazon.fr, and paid accounts that are opened in France, such as Amazon Prime. The tax will also target advertisements where the users are located in France. Put together, the French government estimates that a three percent tax on these transactions will raise €500 million annually.

Three different groups will feel the impact of the new tax: the tech companies, the consumers of those tech platforms, and the client businesses that use digital platforms (advertisers, data users, and service users). Experts estimate that client businesses will absorb about 40 percent of the tax, consumers will have to shoulder 55 percent of the additional burden, and the digital platforms will only bear about 5 percent of the tax’s total cost. US President Trump has promised to investigate the tax, claiming that it discriminates against American companies. The President threatened that his administration might respond to the French digital tax by putting tariffs on important French exports including wine, cheese, and perfume. Should France’s tax on digital platforms succeed in generating government revenue without putting prohibitive costs on consumers, we expect other advanced economies to follow suit in the near future.