On April 26, following stronger than expected US economic growth numbers, the White House’s National Economic Council director, Larry Kudlow, urged the Federal Reserve (Fed) to cut interest rates by 50 basis points.

By repeatedly commenting on the Fed’s monetary policy stance, the Trump White House has broken with more than 40 years of precedent for executive branch restraint toward the Fed. This edition of the EconoGraphic explains the origin of the Fed’s independence, assesses how central banks’ independence affects inflation, and outlines why central banks’ growing responsibilities and macroeconomic influence following the financial crisis might require changes to their institutional set-up.

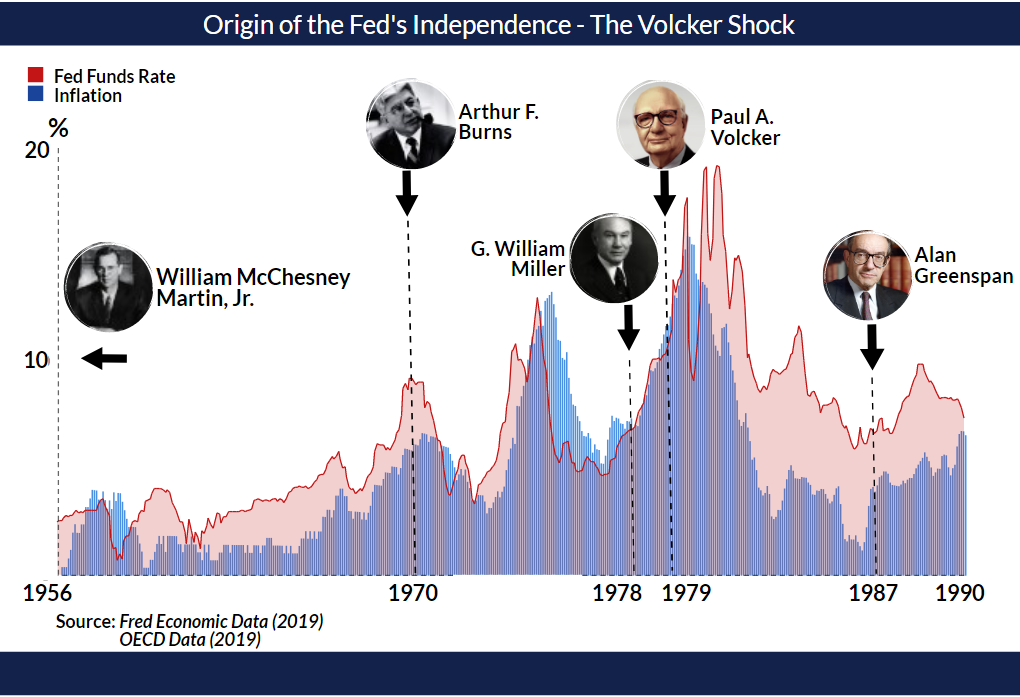

When the US Congress created the Federal Reserve System in 1913, there was no notion that the Fed should be independent from executive or legislative branch influence. As the Fed’s portfolio grew from maintaining the stability of the financial system to setting macroeconomic policy, US administrations increasingly engineered changes in monetary policy for political gains. President Lyndon B. Johnson pressured the Fed to finance his social programs through expansionary monetary policy. Both Presidents Johnson and Nixon relied on the Fed’s easy money policies to bankroll the Vietnam war. The executive branch’s growing influence on monetary policy changed the market’s expectations for future inflation. To counter surging inflation, Congress passed the Federal Reserve Act in 1977 that defined the Fed’s dual mandate of ensuring maximum employment and stable prices. While Congress’ action is considered an important step toward central bank independence, it was President Jimmy Carter appointing Paul Volcker as Fed chair in 1979 that established the precedent of an “arms-length relationship” between the executive branch and the Fed. Volcker moved quickly to significantly hike interest rates to rein-in inflation. The Fed’s decisive action facilitated the US economy’s recovery over the next few years, but also contributed to Carter’s election loss to President Reagan in 1980.

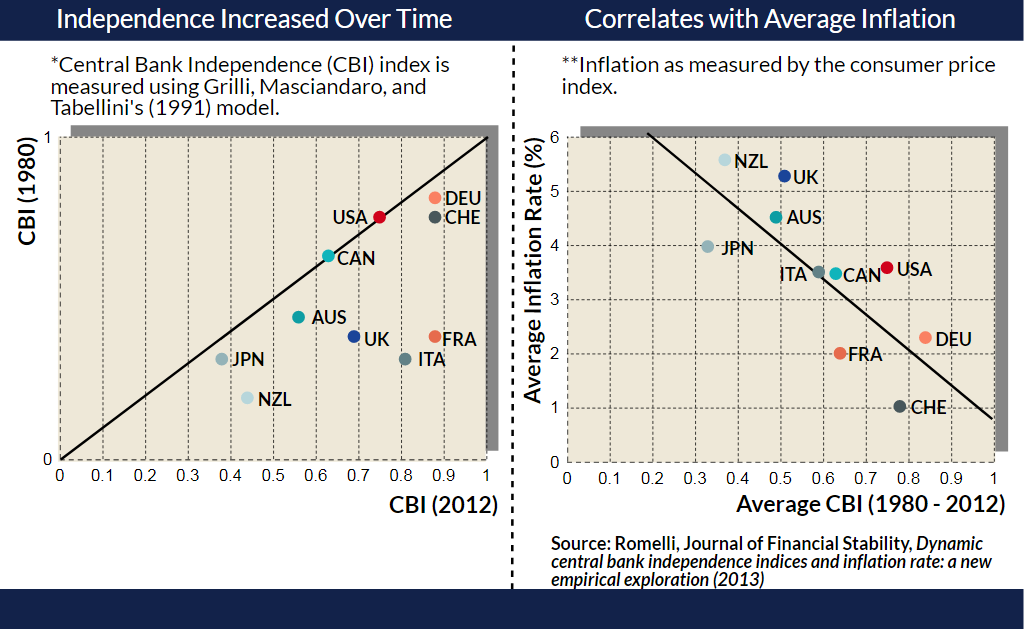

As the Fed became more independent, central banks in other advanced and emerging economies followed the same trend. The featured data shows that between 1980 and 2012 almost all advanced economies’ central banks included in the sample increased their independence. Over the same time horizon, the data demonstrates that the sampled central banks’ independence is negatively correlated with the level of inflation. Central banks with greater independence are part of economies with lower inflation. This negative relationship holds true for central banks in emerging economies as well. Between 1980 and 2000, 26 central banks began to use official inflation targets to “anchor nominal expectations, reduce uncertainty and improve credibility.” Since the 1990s most major central banks aim for an inflation target of approximately two percent. The index for central bank independence by Grilli, Masciandaro, and Tabellini, which we use for this graphic, is based on a political and an economic measure of independence. Recent research suggests that in advanced economies only a central bank’s economic or operational independence (i.e., “the ability to choose an instrument to achieve inflation goals”) has a significant negative relationship with inflation. In contrast, central bank’s political independence (i.e., policy makers’ ability to appoint central bank personnel and set monetary policy goals) does not have a significant effect on price stability. This research aligns well with the long-standing consensus among policy makers and economists that central banks’ mandates should be determined by the government, but a central bank should be able to choose the tools to fulfill the mandates without political interference.

This consensus, however, is under threat as central banks’ responsibilities and macroeconomic influence have grown since the financial crisis. Critics point out that central banks’ accountability has not kept pace with the larger portfolio. Some of the central banks’ new powers, such as a broader financial stability mandate, systemic risk monitoring, and bank oversight, cross the line into areas that are politically divisive. This in turn risks making central bank technocrats players in the political arena. To avoid this outcome, a new consensus seems to be emerging that central banks’ broader financial stability responsibilities should be subject to the same political oversight which already sets the goals for monetary policy. At the same time, central banks’ operational independence to determine the instruments to achieve specified monetary policy goals should remain intact.

Ole Moehr is an Associate Director at the Atlantic Council’s Global Business & Economics Program.